I’d like you to stop for a second and ask yourself, “How many times has someone asked me How are you? today?”

Chances are you’ll probably think of a few. If you went to school this morning, your form tutor probably said it to you, and maybe a few of your classmates or someone at home this morning before you left. The question How are you? is often delivered with meaning. It’s delivered in a way that shows that the person who’s asking it cares. They care whether you feel OK and if you don’t; if you’re not doing well, the chances are this will have a follow up: What’s wrong?

I’m a person who can’t hide my emotions easily, so people know when something’s up. Then they’ll ask me if I’m OK, to which I tend to reply, “I’m good.” The fact is, thought, that around 90% of the time you ask me whether I’m OK or not and I say that I’m good, I’m lying.

My problem is that I don’t do it out of malicious intent; I don’t do it to purposefully lie to you. I do it because I’m trying to keep a secret from you, something I’m scared to share.

I have a mental health disorder. I have multiple mental health disorders.

Since 2012, I’ve carried the diagnosis of OCD and social anxiety upon my shoulders, with the very real possibility of more coming my way in a few weeks time. And this is where my problems lie.

Mental health disorders aren’t unusual, or uncommon: 1 in 4 people have a mental health disorder. To find out how many you know, let’s assume that you know everyone in your phone contact list. So take the number of people you have and divide it by 4. Statistically speaking, there’s your answer.

About 1 in 10 young people aged between 5-16 have a diagnosable mental health disorder. To put that into real terms, that’s about three people in every class. Between 1 in 12 and 1 in 15 young people deliberately self-harm, and over the last ten years the number of young people being admitted to hospital because of self harm has risen by 68%. Nearly 80,000 children and young people suffer with severe depression, and over 8,000 under 10s suffer with severe depression as well.

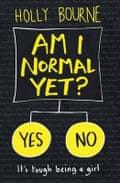

Of course we’ve all heard of books that deal with the issues of mental health, and for me, the book I found that hits the nail on the head perfectly when it comes to mental health is Holly Bourne’s Am I Normal Yet?. She puts mental health into far better words than I can, but then again, that’s why she’s a published author and I’m not, and I think it’s perfect for explaining mental health.

Mental health, then, is neither uncommon nor is it difficult to understand. Yet unless you’re the 1 in 4, it’s easy to dismiss it as something of very little importance, simply because you don’t understand. One of the most important questions I ask you today is the same one Ruby Wax asked her audience at TEDGlobal in 2012: “How come every other organ in your body can get sick and you get sympathy, except the brain?” As someone who suffers from a mental health disorder, I want to help those who are still a bit in the dark to begin to understand.

Anxiety: a panic attack is very difficult to describe. When I enter an attack, I begin to feel palpitations or an irregular heartbeat, and I might begin to find it hard to concentrate and most of the time I feel like I just want to cry.

This might be what the NHS pages say, but let’s put it this way: imagine that your body is an orchestra playing in the Royal Albert Hall in London. You’re the conductor of that orchestra. Let’s imagine someone in the strings section loses their place and begins to play slightly off, but because the percussion need a certain timing from the strings to play their part, that mess up affects them. Because the percussion aren’t doing so good, the brass gets confused and, like a set of dominoes, the orchestra falls out of control and the conductor, who’s supposed to be in control, can’t do anything.

The NHS Choices pages for panic attacks will say that panic attacks are frightening, but harmless. When you have a panic attack, it’s impossible to feel that way. You feel like crying, but more than that, you’re stuck in a valley in your own mind of isolation. You can’t talk, you can’t think straight and, in some cases, it’s difficult to breathe as well. Put it this way: if panic attacks were designed by evolution to keep us safe from external enemies, channelling adrenalin to the heart, brain and muscles as a “fight or flight” response, then as we’ve evolved into modern humans, they have become the enemies. You’re being attacked from within your own system, like something is at work inside you eating away at any feeling you have so all you are is numb. You’re not able to be happy, nor are you able to fight it. And as any CBT therapist will tell you (mine definitely has), part of coping with an anxiety disorder is riding the panic attacks out and doing nothing.

In theory, this makes sense. If you can make it through a panic attack just by riding it out, you’re proving to the part of the mind which you can’t access (yes, such a part does exist) that you can cope and they’re not really that bad. But imagine fighting hundreds of thousands of your own personal demons and you’re close to how difficult it really is fighting panic attacks.

I could save you a hell of a lot of time just by saying: it’s not easy.

It’s sudden, but panic attacks don’t throw you straight down from the top of the mountain. They wind you up with a slow build-up to the main event by which point you’re probably unable to concentrate or do much because all of your efforts are trying to focus on the fact that you’re in danger and you need to get out of danger, but because there is no danger to escape, your panicking stops but then you’re panicking about the fact that you’re helpless, right? You can’t do anything, you have no control over the situation. So what does that mean? You’re panicking about panicking. If I may quote Ruby Wax in the TED talk she gave in 2012 (watch it here), because I think her description matches this quite perfectly: “If the Devil had Tourette’s, that’s what it would sound like”.

But mental health doesn’t stop at panic attacks there. No, of course it doesn’t. You see, I don’t tell anyone, but I carry a bottle of hand sanitiser with me in my blazer that I take to school every day, just in case I touch anything and I need to stop myself becoming ill. I don’t tell anyone, but I wake up some days feeling like my very existence on this Earth is the worst thing that’s ever happened. I’ve told my counsellor that I feel like a burden; the money that the NHS is spending on me could be used to treat someone of cancer. There are days I wake up and head straight for where the knives are, almost falling victim to what the French call l’appel du vide, or the call of the void. The fatal “what if?” question. There’s nothing stopping you, the demons inside my head are telling me, so just do it. Then of course you get the other thoughts. Nobody likes you. That dream job, nobody wants to employ you. You’re worthless. The Guardian’s just publishing this letter because they pity you, and they probably just have a slot to fill. These are genuine thoughts I’ve had, the last one being one I genuinely had when sitting and writing this at my computer.

You get a real sense of shame with mental illnesses. Because nobody understands or because everyone I know will judge me for it, I don’t tell anyone when I’m having a panic attack, or when I feel depressed, and I don’t tell anyone any of my feelings. And of course there’s a real sense of shame too because you can’t show someone the bruises or the cuts or the stitches because if the brain gets ill, it doesn’t show.

Here’s what makes it terrible for me; because I can’t hide how I’m feeling, people know when something’s up. And then of course they’ll always ask, How are you? But I explained the problem with this question a while ago. If I answered that I’m feeling fine, then I’m probably more insane that I thought I was. But if I answered that I wasn’t good today, I can’t (and part of me won’t) put into words how I’m feeling.

My life is a mixture of lies and counselling, alongside a hearty side serving of thoughts and feelings of despair and just general darkness.

The irony of all of this though is that I appreciate it when people ask me how I am. Even though it’s a horrible question for me to answer (because I don’t want to answer either way), I appreciate it to know someone cares. Let me handle the awkwardness of the question, and I’ll lie to you when you ask if it feels awkward.

You see? Mental health is a strange place. But if you keep asking me how I am, maybe one day I’ll feel comfortable enough to stop lying.

Let’s end the stigmatisation of mental health here. Because even though you have no idea who I really am, I’m still the same person I was when you started reading this article. I am not a mental health disorder, a mental health disorder is just part of me. I’m the same person (surprise, surprise)!

Keep asking people if they’re OK. You definitely know some of the one in four, so just keep asking till you get sick of asking and then keep asking. Make an effort to make sure people are OK, and if they’re not then maybe lend an ear for five minutes or so. Please don’t ask someone outright if they have a mental health disorder; they’ll tell you if they feel comfortable, so if you really want to be a friend to someone with a mental health disorder, the best thing you could do is make them feel comfortable.

I’ve learned that when people start talking, the stigma starts to die, so let’s keep talking. Oh, and another thing I’ve learned as well?

I really need to stop lying.