In 1780, a watercolourist and art teacher named Francis Towne set out to see Rome. It was not an original destination for a cultural pilgrimage. Every artist and aristocrat in 18th-century Britain had to make the journey across the Alps at least once to see the splendours of the classical tradition. Some artists even made a living out of portraying posh English people in Italy, or even turned antique dealer to rip them off.

Towne, then, was just another traveller on a well-worn tourist route – even if that route, with its shoddy roads, malaria and bandits, was genuinely dangerous. Yet the watercolours he painted in Rome are astonishing: a compelling vision of a city lost in time and space; a forgotten landscape of ruins where nothing happens and the future is swallowed up by the past.

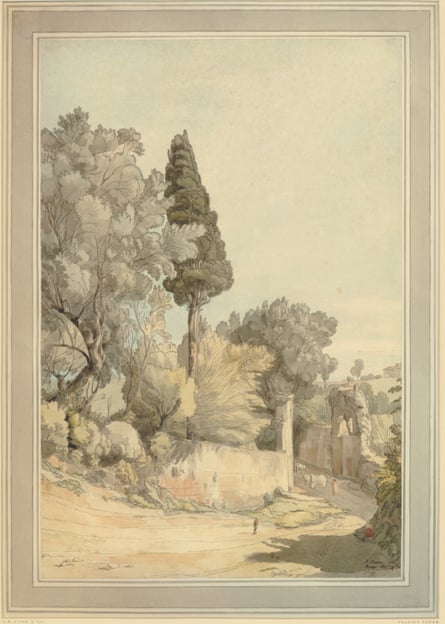

All roads may lead to Rome, but Towne often seems more interested in the path than the destination. Rome here is glimpsed in the distance or seen through trees. He was drawn to the edges, hollows and neglected corners of the city. Instead of gawping at the famous sights, he spent long mornings brushing exquisite luminous views of crumbling walls, cavernous ditches, the backs of palaces, and always above the cypresses, that sky of blue, silver, gold and dappled clouds.

Like the Welsh 18th-century painter Thomas Jones – whose eerily empty view of Naples is included for comparison in this perfect selection – Towne was drawn to crumbling back streets rather than its grand spectacles. Gradually, as you see the ruins through the mottled foliage and tangled branches, you realise his view is not so marginal after all.

These are the great treasures of Rome we are looking at. Towne explores the arcades of the Colosseum, the imperial mansions on Palatine Hill, the ruins of the Roman forum. But when he went to Rome, today thronged with visitors and surrounded by a modern metropolis, these places were lost in weeds and woods.

Towne’s Rome is not a modern living city: it’s a woodland dotted with half-collapsed temples, a meandering countryside populated by a few peasants, antiquaries and market traders, dwarfed by the melancholy remains of a greater past.

While Towne was wandering the seven hills of Rome, the historian Edward Gibbon was six years into writing The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Their visions of Rome are remarkably similar. Gibbon’s masterpiece is an awed attempt to understand how something as vast and powerful as the Roman empire could vanish. Towne’s watercolours ask that same question: what has happened in these sleepy valleys and woods? Temples and palaces that once ruled a huge part of the world are now the decaying picturesque decorations of a pastoral landscape where time seems to have slowed down like the meandering Tiber.

This is not, of course, an objective record of reality. The Tiber does not always flow as gently as Towne shows it, and Rome really did have inhabitants and a modern history when he visited. But Towne is a romantic poet with a watercolour brush. His tranquil and ravishing, yet morbid and pessimistic dream of Rome is a meditation on the death of empires and the vastness of time.

What makes that elegy so touching is the suggestive nuance of Towne’s perfectly observed natural details. A splash of trees on the horizon, a curl of roots in the foreground, a wash of green, a whiteness of sunlight. His technical mastery makes the imagination soar.

Francis Towne, who failed 11 times to get elected to the Royal Academy but had the foresight to leave these watercolours to the British Museum when he died in 1816, may not be a famous British artist. He is however, as this entrancing exhibition reveals, a great one.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion