Mike Galsworthy: “The impact on science of the Brexit vote is real and it’s happening now”

On the evening of the referendum vote, I was at the Stronger In campaign headquarters watching the results come in. I’d spent a year, since co-founding Scientists for EU in May 2015, battling to explain why UK science was better off in the EU. We were nervous, but all the polls had indicated a win for Remain. Yet through that otherworldly night, a very different set of results trickled in…

So now we start, with heavy heart, to pick up the pieces. About two weeks before the vote, I developed two plans: one for the event of a Remain vote, the other for Brexit. A vote to stay in the EU would have allowed us to exploit the hard work and insights gained over the past year. The UK’s presidency of the European Council, scheduled for the second half of 2017, would have been a real opportunity to promote science and innovation, building on the momentum generated by the recent Dutch presidency commitment to open science.

Now it feels like we have been hauled from the driving seat of the world’s science superpower and thrown onto the side of the road. What to do? We have no choice but to invoke Plan B: fighting to insulate what we can, and setting up systems to monitor the fallout.

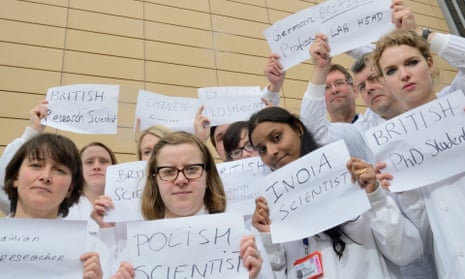

As the Guardian reported this week, the effects of the vote are already being felt across UK research. We are well aware of these dynamics, watching them on our social media and via our “Brexit impact” form, which has already collected over 300 entries. We see cases of overseas students and researchers planning on working in the UK who have been put off (10 per cent of our databases entries). We see Horizon 2020 consortia under formation, where UK coordinators have been advised to step down to a lower role, or to leave altogether, so as not to jeopardise funding (another 10 per cent).

There is also a sense of deep sense of frustration, with many respondents (21 per cent) declaring they want to leave the UK when the opportunity arises. Several cite increased racism and xenophobia in the country (12 per cent of entries). Compounding this is the wider anti-expert tone of the referendum debate and surveys showing a level of distrust of academics among those that were voting to leave.

Of course, we remain technically within the EU – for now. And we await some kind of deal, tied up with freedom of movement, which can hopefully secure our continued participation in Horizon 2020, albeit on diminished terms. But if we want to rescue British science from the current mess, we have to assert ourselves, enter the public and political arena, and fight for our vision.

Dr Mike Galsworthy is programme director of Scientists for EU, and a visiting researcher at London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine.

Anne Glover: “We urgently need a post-Brexit strategy for British science”

As a science community, we must identify what options we now have and make clear statements about what the UK will win or lose from any deal struck for science in the Brexit negotiations. The advantage of being a full member of the EU was obvious to scientists themselves, with only a tiny minority supporting Brexit. But we should be clear that this overwhelming support for Remain wasn’t just about self-interest. The output of our science, technology and research base has a profound impact on every citizen, every minute of every day, through medicines, communications, navigation, sustainable energy, clean air, water and safe food - the list is endless.

The UK has had disproportionate levels of success in securing EU research funding, relative to our contribution. But just as important is our ability to influence the strategy on how

What are our other options? We could participate as a non-associated or third country like Turkey. We would not be eligible for all H2020 activities and could not propose research grants but, if invited, we could become a partner and would have to cover the costs of our participation. This is possible without agreeing to free movement of people.

The UK government could make up any resulting shortfall in UK research funding. But first, in the Brexit negotiations, we need to see how much of our current position we can protect.

Non-EU countries such as Norway can participate in all of the EU’s Horizon 2020 programmes, through membership of the European Economic Area (EEA), but this brings an obligation to agree to the free movement of people in return. Norway’s contribution to the EU is €107.4 per capita, compared to the UK’s current contribution of €139 per capita. But they cannot influence the strategy in any way.

I think that this is probably the best we can hope for. However, I do realise that it depends upon the UK agreeing to free movement of people (not just scientists) and that restricting immigration was central to the Leave campaign’s arguments. There is a precedent here: when Switzerland voted to restrict immigration in 2014, they were disbarred from key parts of Horizon 2020 overnight.

At current EU funding levels, this would come close to £1 billion per annum, or twenty per cent of our entire research budget. There is no evidence that the present government has any appetite for this: research funding has fallen due to inflation since 2009. During the same period, our funding from EU sources increased by 68%.

Although European Commissioner Carlos Moedas has made it clear that UK will enjoy full eligibility in Horizon 2020 until a Brexit is agreed, there are already signs that our EU partners feel uneasy about including us on future proposals.

As scientists, we must be loud, visible and persistent in persuading the Brexit negotiating team to secure full access to Horizon 2002, with all the rights and obligations that entails. Otherwise, the quality and impacts of our science will decrease, and the best and brightest minds will start to head elsewhere.

Professor Dame Anne Glover is vice-principal for external affairs and dean for Europe at the University of Aberdeen, and was chief scientific adviser to the president of the European Commission from 2012-2014.

Andy Stirling: “Both democracy and science depend on avoiding comfortable blinkers.”

These are grim days for British democracy. Early indications of the implications of Brexit for UK research are worryingly clear. Less obvious – but deeper – are the lessons from the political trauma of recent weeks for relations between science and democracy.

According to its own cherished identity, science is about “truth”. To properly get at truths, requires open, respectful, reasoned contestation – free (though only ever partly) from the fetters and pressures of power. So science arguably flourishes most through energetic strivings towards democracy. Without this, it can become vulnerable.

This is why, so much history and philosophy suggest (often romantically) that democracy and truth are deeply linked. Neither is fully realised without the other. Each is plural, complex, uncertain and slippery. Both are often abused through special pleading. To over-assert claims to either is damaging. Yet to undervalue them is even more harmful.

Much needed, then, are democratic virtues like equality, pluralism, social justice, solidarity, trustworthiness and reflective deliberation. Without these, referenda are clumsy lightning rods. So what are the implications, when society suffers a collapse – not only in these political qualities, but in our ability to notice their decay?

What to make, for instance, of how lies have become routinised in mainstream politics? How to act, when democratic institutions and arenas become saturated by narrow elites? What if the most emphasised values and aspirations in politics, are deeply undemocratic? What to do, when ‘democracy’ itself is invoked as cover for uglier sectional agendas? How to reverse the resulting corrosive exclusion, cynicism, fear and pent-up violence?

Both democracy and science depend on avoiding comfortable blinkers. So each of these questions should therefore be taken seriously. To point to the smothering of British democracy by oppressive privilege is hardly contestable. And despite routine insinuations in jingoistic Brexit rhetoric, our democracy manifestly compares unfavourably to the rest of Europe. The European Union has (for all its flaws) been the most important source of faltering progress, and much euroscepticism specifically resists empowering democratic EU institutions.

Even more insidious are calls to “take back control”. In a dynamic, uncertain world, sovereign control is always a fallacy. As Harold Macmillan noted at the post-war height of imagined UK power, the greatest shapers of history are “events, dear boy, events”. Claims to control are little more than fig leaves for privilege as it surfs events.

Facing outward from power, such talk of control is profoundly undemocratic. When targeted against foreigners, immigrants and refugees, it is a code for racism. To identify this is not to call names. Racism is a pathology of ideas, not people.

These perversities matter. When control is disappointed (as is inevitable), bigotry slides into violence. So turns the grinder of “post-truth politics”: as truths are neglected, democracies weaken in their capacities to build truths. Too many, myself included, saw only very late how serious this vicious circle has become.

But a hope amidst the anguish and anger is the spur this crisis provides to renewed striving. Imperfect journeys, rather than boasted arrivals, respect for truth and democratic struggle are mutually reinforcing. As those steeped in the politics of science know well, the stakes were never higher. Step by step, the challenge is nothing less than building democracies anew.

Andy Stirling is professor of science and technology policy at SPRU, University of Sussex.

Kate Hamilton-West: “Values hold the key to moving forward”

Working at the University of Kent, which describes itself as “the UK’s European university” over the past three weeks has been very strange. I’m surrounded by people looking shell-shocked. It has become impossible to walk along the corridor without engaging in Brexit talk. And the university feels like a sanctuary, a safe haven for those of us that wish that the news on 24 June was just a bad dream.

Europe is important to me in ways that I don’t think I fully acknowledged until now. I feel angry, grief stricken – the part of me that is a human being, a parent, a friend feels this deeply, while the part of me that is an academic - a psychologist - wants to analyse, rationalise, problem solve.

There has been much talk on social media about the causes of the divisions our country is now experiencing. The vote has been analysed demographically, politically and economically. Some of this is fascinating, and helpful for understanding where we are now. But more important than this is the recognition that our country is diverse, we have among us a broad range of opinions, priorities, and concerns for the future.

We cannot see half the nation as the culprits, responsible for destroying the hopes, aspirations and values of the other. We need to get to a place where we can engage in dialogue, heal wounds, find common ground and understand each other. We need to reject divisive labels too: both ‘leavers’ and ‘remainers’ are first and foremost individuals, and their identity cannot be reduced down to which box they checked on 23 June.

Over the past three weeks, many of us have experienced a range of negative emotions. While instinct might tell us to push these away, it is important that we don’t. Suppressing negative emotions causes them to rebound, become stronger, and intrude more and more into our daily life. So, what do we do instead? We need to embrace our emotions - look at them and understand why they are there.

My own feelings of anger stem from the way the referendum was handled, more than the outcome. The false promises, later retracted, were shameful. The surge of racist incidents in recent weeks is completely intolerable. My feelings of grief stem from loss of the country I thought I lived in – where people were polite to each other and my children didn’t come home from school asking if their European friends would have to leave.

Recognising our feelings and where they come from is important because it tells us what we value. We are angered by injustice because we think justice is important; we are saddened by the loss of decency, respect and tolerance because these values matter.

To move forward, we first need to recognise what is within our control and what is not. There has been a lot of talk about if, when and how article 50 will be invoked, but this is not within our control.

Once we have accepted what we cannot change, we must change what we cannot accept. If we cannot accept injustice, we must fight it where it arises. If we cannot accept living in a country that is devoid of decency, respect and tolerance then we have to uphold these values, live by them, be the future we want for our country.

If we cannot accept the type of politics that led to this, then we must become part of a different type of politics, one that is more consistent with our values and sense of right and wrong. We must also be willing to stand up for what matters to us professionally. As an academic, I cannot accept the culture of misinformation and denigration of experts that prevented many people from making an informed choice. Part of my commitment to building a better future is to address this in any way possible.

Dr Kate Hamilton-West is a senior research fellow in the Centre for Health Services Studies (CHSS), University of Kent.

Andrea Saltelli & Silvio Funtowicz: “Science cannot solve these problems alone because it helped to create them in the first place”

Scientists frequently lament the lack of attention paid to “known facts” by decision makers and the public. With Brexit, it appears that a post-factual era has arrived, with politicians like Michael Gove openly expressing their disdain for expertise. How and why has this come about?

Science is living through an unprecedented crisis of reproducibility, with an associated loss of efficiency, waste of resources, and an impressive list of misdiagnoses in fields from forensics to economics, medicine to psychology, and nutrition to chemistry.

Science’s internal quality control mechanisms have been seriously impaired by dysfunctional system of incentives, including the use of perverse metrics, and the imperative to publish or perish, creating a dystopian nexus of Gordian complexity. The specialization of science, its subjugation to market ideology, and the loss of its pristine social fabric have contributed to this process. As a result, trust in science and expertise has suffered. Is such scepticism unjustified?

We still purport to live in the age of the enlightenment. Science can confirm the existence of gravitational waves and place a probe on a comet flying past the sun. We live in a world where the functioning of most of what surrounds us, from technologies to institutions, escape our understanding.

We have come to accept that democracy is dependent on financial manipulation. We pretend to make evidence-based policy, but suspect that evidence is used against us by those who operate the policy machine. The enlightenment is collapsing yet its worldview is still unassailable, even as a new “endarkenment” takes hold. Activists, scientists and citizens may have good ideas and sincere intentions, but their voices hardly register in the cacophony.

Science cannot solve these problems alone because it has contributed to create them in the first place. Scientists should not assume that science is an ethically privileged system. They should avoid supporting controversial policy agendas or corporate interests, or denouncing legitimate perspectives as “anti-science”. Scientists’ passion and advocacy is best deployed when they speak from within the confines of their own craft and specialised knowledge, showing humility and awareness of their own ignorance, as well as expertise.

Solving this crisis won’t be the task of single individuals, constituencies or institutions. There are already proposals for technical solutions to the present system of perverse incentives, on issues ranging from metrics to peer review; and swift action is also needed to address recognised methodological pitfalls (see, for example, the ASA’s statement on P-values). Other problems related to quality, diversity and inclusion need to be addressed and post-normal science (as suggested by New Zealand’s chief science advisor, Sir Peter Gluckman) may offer a bridge between institutions and actors to be mobilised.

These, and other creative initiatives, some developed in collaboration with other concerned citizens, will demonstrate the determination of the scientific community to engage in a democratic endeavour, reinforcing human rights, and extending them to the excluded.

But we have to acknowledge that a complete solution is not possible unless we address the core beliefs from which our present predicament has emerged. In the seventeenth century, at the dawn of the scientific age, Francis Bacon suggested the need to understand which idols need to be abandoned before we can achieve progress. Bacon’s battle against scholasticism would today take the form of a collective debate about the existing idealised vision of science and scientists. Next, having witnessed the failure of economics to anticipate and solve recent crises, a reappraisal of its role as a master discipline to adjudicate human affairs is called for. For economics to offer useful recipes – including to Brexiteers – it need to solve its own cyclical internal crisis of relevance.

Andrea Saltelli and Silvio Funtowicz work at the Centre for the Study of the Sciences and the Humanities (SVT) at the University of Bergen (Norway). Andrea Saltelli is also a member of ICTA at the Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona (UAB).

Tony Strike: “Universities and researchers can’t wait two years. We need answers and assurances now.”

After the referendum result a friend of mine wrote on social media: “I don’t want to hear anyone whinge for more than a day, get out there and DO something about it. We all need reassuring hugs, and to get on with it.”

It was a good reminder. As director of strategy at the University of Sheffield, I know only too well how vulnerable our universities are to an exit from the EU, and the need to reduce policy uncertainties as we plan ahead.

Everyone should care about the damage higher education will suffer because our universities serve all our economic and social goals. They educate our children, support innovation, bring wealth to the nation. The arguments go far beyond what might be perceived as an educated elite defending their interests, or access to money and resources.

UK universities have in the region of 100,000 collaborative links involving UK-based researchers working with European counterparts. 60% of all internationally co-authored research papers produced by UK scientists include a European co-author. EU money enables our universities to work together across a continent, to lead multinational collaborations, and to share in European resources, data and expertise.

What we now need from Theresa May’s cabinet is a firm commitment to securing our ability to continue collaborating with our European partners. Recent ministerial statements stop short of making that commitment. It’s true of course that we will have a two-year period to negotiate Brexit. But research grant applications are already in trouble because of the current policy uncertainty.

Student mobility is also good for our young people and for the international character of our universities. 200,000 UK students have studied or worked abroad through the European Erasmus programme. We need our politicians to guarantee our university students freedom of movement through Europe so they can continue to study abroad.

Large numbers of European students also come to the UK. A Universities UK analysis, based on 2012 figures, found over 125,000 students from other EU countries in the UK, generating £3.7 billion for the UK economy and supporting 34,000 UK jobs. This is all at risk. Non-UK EU students have been told they can access student loans but have no assurance on fees. We need a political guarantee that EU students coming to the UK this and next September can pay UK/EU fees for the duration of their study.

And one in five academics in our top research universities come from elsewhere in Europe, but are now uncertain whether they will be allowed to stay. Imagine the brain drain and loss of national capability if one in five researchers, treated as migrants, decided to leave.

If the UK leaves the EU without free movement, our recruitment of staff would become subject to restrictions through the tier 2 (highly skilled) visa route, with an annual cap on visa numbers which is already oversubscribed. We need the government to guarantee that academics, as highly skilled knowledge workers, will have freedom of movement across the continent.

Those of us who work in universities will get on with it, but politicians must give us the assurances we urgently need. It is not enough to tell people who are helping find new cures for diseases, keeping us safe from cyber attack or creating jobs in local industry that they have to wait two years for answers. They need to know now. If they don’t, the loss to our universities, our society and our economy will be devastating.

Dr Tony Strike is Director of Strategy at the University of Sheffield.