After four decades of debate, India’s plans to connect its rivers finally got underway last September. Drums were played, bright yellow flowers were thrown and mantras were chanted. Farmers and journalists waded into the brown waters of the Godavari river as the first pumps of the Pattiseema irrigation scheme were turned on, lifting water into a canal and down towards the Krishna river.

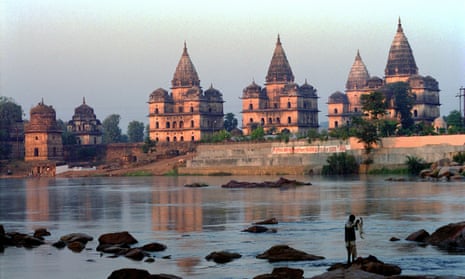

“History will be made today,” tweeted Nara Chandrababu Naidu, chief of the large state of Andhra Pradesh. The linking of the Godavari and Krishna rivers is the first, temporary part of a vast engineering scheme billed to connect 37 rivers in India through the construction of 15,000km of canals, thousands of water storage structures and 34 gigawatts of hydroelectric power. The Pattiseema project is due to be fully completed by March. Further north, a second scheme to link the Ken and Betwa rivers scheduled for construction in December has been delayed.

The government believes the national river linking project will simultaneously tackle the country’s acute problems with flooding and drought by diverting “surplus” water from flooded areas into those with a deficit. It has also been presented as a solution to hunger – a problem that pervades India, now home to the second highest number of undernourished people in the world according to a report by the UN. The government claims the scheme will create an extra 35m hectares of irrigated land.

But not everybody is celebrating the implementation of a plan first envisioned by the ministry of irrigation in 1980. Critics have warned that it could have enormous negative impacts, from the large-scale displacement of populations to the submersion of forests and national parks, home to endangered tigers.

The management of water has long been a political issue in India, with hydroelectric projects often provoking action, but the vast plan to link its rivers pits the interests of states both against each other, and against what is viewed as being in the national interest.

Activists let the issue lie during the ruling years of the Indian National Congress who abandoned the project, but Narendra Modi’s BJP party – elected in 2014 – is fast pushing it forward. Meanwhile, civil society struggles to mobilise against the project because of a dearth of information and lack of due process, they claim.

Himanshu Thakkar, an engineer who coordinates the South Asia, Network on Dams, Rivers and People (Sandrp), which monitors water governance in India, said: “It’s a long and slow struggle. They are not viable projects, there are no specifications. We need a democratic process to inform decisions [and] proper environmental, social and hydrological impact assessments. Only then can we come to the right scientific conclusions.” The network has been scrutinising the proposals and writing to project developers and government bodies to demand information.

According to Sandrp, the Godavari-Krishna link could be “illegal, unnecessary and misconceived” because an environmental impact assessment (EIA) has not been done. They also challenge the claim that the Godavari river basin has “surplus” water. It is home to Marathwada, an area known as “India’s emerging farmer suicide capital”. With the area experiencing the country’s highest level of rainfall deficit during last year’s monsoon season – which followed three years of drought out of four – farmers have struggled to maintain the crops and finances needed to keep operations afloat.

Amid fear of natural disasters, people have been more open to viewing river linking as a solution and NGOs have been unable to counter their arguments with action, says Narasimha Reddy Donthi, a public policy expert who has been analysing the Godavari-Krishna link.

Opponents say that a lack of due process has also made it difficult to challenge the Ken-Betwa project. Although an EIA was completed for this section of the plan, experts say it is flawed.

“It underplays that the 10-year construction period would not only impact the area involved, but the whole landscape would be devastated,” says Pushp Jain, the director of the EIA’s Resource and Response Centre which monitors environmental clearance processes for the Legal Initiative for Forest and Environment. Jain believes the EIA underestimates the impact on two protected areas – the Panna tiger reserve and Ken Gharial wildlife sanctuary – as well as the cumulative impact of multiple projects in the region which include a major thermal power project and mining giant Rio Tinto’s diamond exploration plans.

ERC also say the government has failed to adequately consult the public. Two public meetings were held a year ago in Madhya Pradesh, but none were held in the other affected state, Uttar Pradesh. Sandrp claim that public consultation documents were only available online on the day of the second meeting, were not published in local languages, and mandatory advance notices of the meetings weren’t issued to village administrations.

Joanna Van Gruisen, a wildlife photographer who runs a small tourism retreat on the banks of the Ken river, attended the meetings and recalls that local villagers, including school children and NGO and political representatives were unable to voice their objections because BJP party workers shouted them down.

“There will be community conflicts [and] long drawn out litigations,” says Jain. And indeed conflicts are already starting. Some land owners who expect their land to be submerged or built upon are demanding – and in some cases successfully claiming – compensation from the state or central government.

But this may not be to the advantage of those who oppose the project as a whole, says Medha Patkar, head of the broadly leftwing National Alliance of People’s Movements (NAPM).

“In Andhra Pradesh there has been a lot of questioning and agitation by farmers but it has not come to anything because the state has played a number of games. It’s trying to divide people and some have accepted the compensation,” says Patkar.

“We must reach out to each area, disseminate information and build awareness. We will rise up and take a strong position.”

The Indian National Water Development Agency did not respond to the Guardian’s requests for comment.

Join our community of development professionals and humanitarians. Follow @GuardianGDP on Twitter, and have your say on issues around water in development using #H2Oideas.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion