Reno Is Gambling It All on Tech

With Tesla and Switch moving to town, the city unveils its tech ambitions.

RENO, Nev.—The first thing that catches the eye on the approach to Reno is a cluster of casinos rising from the valley, a tangible sign of the city’s history as a gambling destination.

But if the orange glow of Circus Circus and Silver Legacy’s moon-like dome entice visitors by night, by day, they are drab reminders of a past this city of 240,000 wants to outgrow.

It is in the midst of trying to reinvent itself as a center of tech innovation where graduates of the University of Nevada’s Reno campus would actually want to live.

Already, there are signs of progress. On the outskirts of town, Tesla is building a gigafactory expected to create 6,500 jobs by 2020. Drone companies, drawn by the area’s status as one of a handful of commercial testing sites, have settled into the area in the last couple of years. Las Vegas-based Switch, Apple, and the cloud company Rackspace have all recently announced new data centers. The city dubbed a stretch of downtown Start-Up Row, and a popular coworking space has given rise to local entrepreneurial ventures.

The transformation isn’t a mere facelift. Reno’s economic health and prosperity depend on it.

Gambling tourism is down and people are more apt to head for the slopes and casinos of Lake Tahoe 40 miles southwest. Reno cannot compete with Las Vegas in terms of entertainment and restaurants, and there is little else to draw vacationers here. The housing-market crash hit locals especially hard, and downtown is dotted more with cheap motels than apartments where software engineers would want to reside.

While city officials say the current revitalization has been in the works for years, the Tesla announcement has lent a certain legitimacy to the idea that the city is a budding destination for tech companies, and sparked a sense of hope among locals that pulling this casino town into the 21st century is possible.

Yet, if Reno wants to supply talent for the growing number of tech-sector jobs, the city will need to improve how it educates and trains residents to join the new knowledge-based economy. The city is “pinning a lot” on companies like Tesla and Switch, said Eric Herzik, a professor at the university, noting that Reno has tried to woo businesses by touting low taxes and living costs, as well as its proximity to Silicon Valley. But low costs won’t necessarily be enough to attract workers who can afford to take their skills to culture-rich cities like Austin.

“I think it’s a work in progress,” said Mike Muro, director of policy at the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, and one of the authors of a report that suggests Nevada has not done an adequate job of aligning education policy and workforce needs, particularly when it comes to the science, technology, engineering and math (STEM) fields.

In 2013, the report found, 15 percent of the state’s jobs required “a high level of knowledge in at least one STEM field,” whether a four-year degree in computer science or lower-level technical training. Those jobs have driven a significant portion of the state’s economic recovery, helping lower unemployment from 14 percent in 2010 to around 6.4 percent today, and paying 28 to 68 percent more than non-STEM jobs. Yet, the average STEM job in Nevada takes 30 days, or a week longer than non-STEM jobs, to fill. Three-quarters of local kids don’t earn bachelor’s degrees.

In many ways, Muro, whose department looks at demographic and social changes happening in metro areas around the country, added, “what’s happening in Reno is an extreme example of the kinds of challenges many of our metropolitan areas face.” From Detroit to Houston, cities around the country are grappling with how to grow their supplies of middle-skill STEM workers.

Where producing qualified workers wasn’t a major challenge when the casinos were booming (“It doesn’t require a degree to flip cards,” one resident said), the years of coasting are over.

“We don’t have that luxury anymore,” said Mike Kazmierski, the president and CEO of the Economic Development Authority of Western Nevada during an interview at his office just south of the Reno airport. “We need educated people.”

So the city has adopted a multi-pronged approach that involves ramping up STEM education in schools, strengthening its relationship with the university, and bringing more restaurants, housing, and culture into downtown to convince workers that Reno is a desirable place to live.

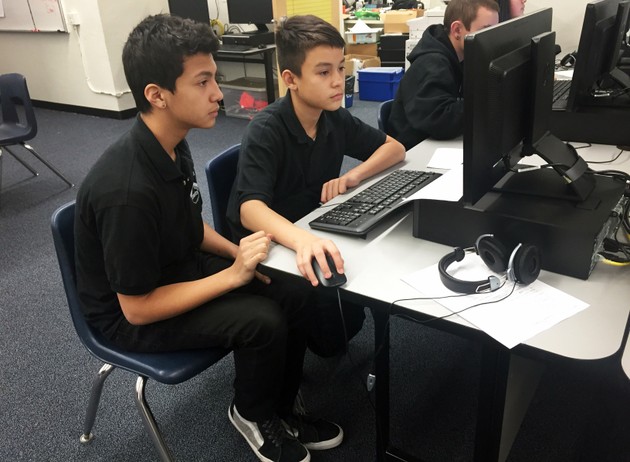

On a recent Friday at Dilworth STEM Academy, a formerly struggling middle school just east of Reno in Sparks that has been reworked with a math and science focus, eighth graders Daniel Villasenor and James Tidwell are researching robots online. Later in the school year, they’ll learn to build and program them. There’s not a textbook in sight. Lea Bell, their 33-year-old teacher, received training in how to teach the course through Project Lead the Way, a nonprofit that offers professional development for STEM instructors.

Across town at the career-and-technical high school in Reno, transformed in 2009 from a part-time school for juniors and seniors into a comprehensive full-time school offering both core academics and career training, engineering has become one of the most popular courses of study. Tesla, instructors and students said, visited the campus and told students, “We want you to come work for us.” The company will contribute $37 million to K-12 education in the state over the course of five years, and $1 million to battery research at the University of Nevada Las Vegas. Tesla did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

While these steps to expand STEM education, particularly for younger children, are promising, Nevada is among the worst-performing states in the country when it comes to education. A recent Education Week report gave the state an F on education spending and just a D+ on adult outcomes. Washoe County, where Reno is located, has a graduation rate of 75 percent, higher than the state’s 70 percent average but below the national average of 82 percent. While the state’s white students graduate at a rate of 77 percent, just 65 percent of Latino students and 54 percent of black students do.

Kelly Cannon, the science program coordinator for the Washoe County School District, said the district has made progress in increasing its STEM education in recent years, but acknowledged that a lack of professional development for teachers means some STEM-related resources sit unused. The state, Reno included, has also been plagued by a serious shortage of qualified science and math teachers.

To help fill the gap, the University of Nevada’s Reno campus last fall joined UTeach, a national effort to produce more STEM middle- and high-school teachers. The university, which recently began offering a minor in batteries and energy storage technologies, in September unveiled the InNevation Center in a midtown space it acquired from the city. The center, to which Switch contributed half a million dollars, is intended to serve as something of a start-up incubator for both students and community members. That the center is downtown and accessible to non-students (for a membership fee) is an important step. Interstate 80 divides the university from the bulk of Reno and multiple people interviewed for this story faulted both the city and school for largely ignoring each other for years, but said there is increased conversation about how to make Reno more of a college town à la Boulder, Colorado, than simply a town with a college.

“We want to really engage with the community … and foster that connection of people and students and businesses,” said Heidi Gansert, a university spokeswoman who served in the state assembly and is running as a Republican for a state senate seat.

The university’s engineering college, which Gansert said has doubled enrollment in the last 10 years, runs a mobile “engineering-education laboratory” that it took to 320 classrooms in 2014.

The trick, Muro, the Brookings fellow, noted, will be to quickly scale up the number of STEM graduates in a way that, when the casinos were booming, wasn’t important. “It’s really a major cultural shift,” he said. Kids who might become interested in tech through the mobile lab, for instance, are years from entering the workforce, and tech companies are working on a much tighter timeline.

“Nevada’s P-12 public education system and its universities and colleges must begin to ameliorate the state’s existing proficiency crisis if Nevada hopes to prepare greater numbers of students for future opportunities in STEM occupations,” reads the report.

While the city works to produce graduates who are qualified to fill tech jobs and attract companies like Tesla with cushy tax incentives, convincing young people who might be eyeing the vibrancy of a place like San Francisco or Austin that Reno is right for them is another matter entirely. Reno isn’t immediately appealing the way such cities are, but midtown boasts an increasingly vibrant restaurant scene, with hip outposts like Bowl offering diners seared scallops with sunchoke-potato gratin, creamed spinach, and fennel relish for $18. And nearby, a cafe that would be at home in Brooklyn has brought people back to the riverwalk.

Downtown, the former post office reopened as a would-be Chelsea Market, with a juice bar and chocolate and flower shops. An adjacent plaza and bridge are slated to be complete by June. A few blocks east, bars and restaurants have gone up near the new minor league ballpark in the so-called Freight House District. Dotted around the city are works of art from Burning Man (the annual festival takes place in the Black Rock Desert, northeast of Reno). The non-gaming hotel Whitney Peak is gaining traction.

Reno is “on a path to rapid rebirth,” Kazmierski said.

But even he acknowledges that producing enough affordable housing is a concern. Home prices have doubled in the last four years. The city will also have to contend with casinos clinging tightly to the city’s gambling roots. Even with the revitalization effort underway, they are still the city’s most dominant feature.

Bob Fulkerson, the state director of the Progressive Leadership Alliance of Nevada and a longtime resident of Reno, worried during an interview at his office along the river that the city has become a place for “resource extraction.”

“We want that money to stay here to build wealth for our families,” he said.

But while city officials like Kazmierski say they are committed to supporting local students and workers, they also have no qualms about attracting big-name companies and new residents to Reno.

“We’re going to have to attract talent to the region,” Kazmierski said.

Muro agrees. Regardless of the growing pains, the opportunity to become a tech hub is a good one for the state. It’s impossible, he said, to underestimate “the symbolic and material importance” of that opportunity in forcing a push toward a more diversified, sustainable economy.