You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

Getty Images

More and more universities are experimenting with hiring multiple scholars into one or more departments based on shared, interdisciplinary research interests. That’s in part because cluster hiring, as it’s called, can be an effective way to approach big-question or 21st century challenges-type research goals. Cluster hiring also can help lead to increased faculty diversity, which is a top priority for many campuses right now. And in an era when many administrators say they can't support growth in or even fill all vacancies in departments, cluster hiring provides a way to make a splash in high-profile fields that enhance institutional reputations.

While there’s no one right way to launch a cluster-hiring initiative, there is apparently a wrong way -- at least according to preliminary faculty responses to a cluster-hiring program at the University of California at Riverside. Results of a survey of professors’ reactions to how the initiative has gone so far are pretty damning, but provide potentially valuable insight for other colleges and universities considering such programs.

“The process was chaotic, disorganized and very opaque,” reads one narrative survey response, echoing dozens of others expressing similar criticisms. “Enormous amounts of the faculty’s time was wasted. … We’ve been given new instructions repeatedly, have had to redo job descriptions and must search for all the positions simultaneously, which will be very difficult. I doubt the outcome will be good.”

In 2014, Riverside’s new chancellor, Kim A. Wilcox, proposed several key areas of focus for the campus, including increasing the faculty by 300 professors, to about 1,000, by 2020 -- a number indicating real growth after years of tight budgets for public higher education in California. Another priority was accelerating campus construction and infrastructure improvement projects. Related to those goals, Paul D’Anieri, the university’s new provost, started soliciting cluster-hire proposals that same year, in December.

In a memo to professors, D’Anieri said the goal of the program was to hire scholars “with promise for excellence in both research and teaching,” build “nationally visible” programs, and diversify the faculty. Proposals could be submitted by individuals, groups of faculty or larger academic units, he said, and would be reviewed by a dean’s council and a faculty panel convened by the vice chancellor for research (with representation from the Academic Senate). Final decisions would be made by D’Anieri, in consultation with these groups.

The provost and the vice chancellor for research reserved the right to request proposal revisions or recommend combining proposals that seem redundant or complementary. Proposals were to be evaluated by their potential to attract exceptional faculty, likelihood of increasing performance on appropriate competitive metrics (such as fellowships or federal funding) and ability to bring programs into the top fifth of national rankings and put Riverside at the leading edge of emerging fields. Proposals’ likelihood to contribute to faculty diversity and complement existed programs also were listed as criteria.

The memo included a template for proposals, saying they could be no more than 12 pages in length. Proposals were to address the future importance of the research area, existing on-campus assets, new assets needed and whether the proposal involved multiple departments or colleges. How many hires would the cluster entail, D'Anieri wanted to know, and how quickly could these professors be recruited? (The deadline was three years.) How would the cluster contribute to diversity, and what had the academic unit done previously to diversify?

An informational meeting was set for January, with proposals due at the end of February 2015. Initial allocations were to be made by May.

Some 130 proposals were submitted and evaluated by boards including faculty members and administrators. That yielded 26 approved clusters, from human neuroimaging to the global arts, and 80 associated new faculty lines. Searches are now under way for those professors.

On paper, the idea was appealing to many professors. In reality, the process was anything but smooth. Almost immediately, faculty members complained that the guidelines for cluster proposals were vague. Later, they accused administrators of controlling the proposal selection process and selecting clusters arbitrarily or, worse, for their own ends. The massive cluster-hiring initiative also seemed to be overtaking established, department-level search procedures, they said.

While the first wave of clusters already has been approved, the recruitment process is still happening. Part intervention, part response to faculty concerns, the Riverside division of the Academic Senate recently surveyed its members on their views of the initiative thus far. The results were released to faculty members earlier this month, and Inside Higher Ed obtained a copy. A little less than half the faculty -- some 330 professors -- responded, indicating a high level of interest in the matter. The idea is that the body will use the responses to offer constructive feedback and guidance to the administration in the coming weeks.

Here’s what the survey found. First, most respondents -- 82 percent -- said their departments already had strategic hiring initiatives in place before the clusters. Some 49 percent of all departments have been able to fill all open positions on their own.

Most of the respondents either agreed that or were neutral as to whether there was sufficient time to prepare cluster proposals (41 percent of respondents were not involved in any proposal). But 72 percent of respondents either disagreed or strongly disagreed that criteria for proposals were clear.

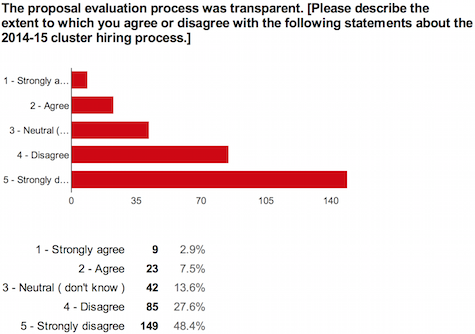

As to the proposal evaluation process, 76 percent disagreed or strongly disagreed that it was transparent. Just 14 percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that the feedback they received on their proposals was appropriate, compared to 45 percent who disagreed or strongly disagreed (the rest were neutral).

Some 46 percent of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that the provost’s appointed steering committee for the initiative did a good job, compared to the 14 percent who had a positive view (40 percent were neutral). Nearly half of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed that members of the selection panel knew enough to properly assess proposals.

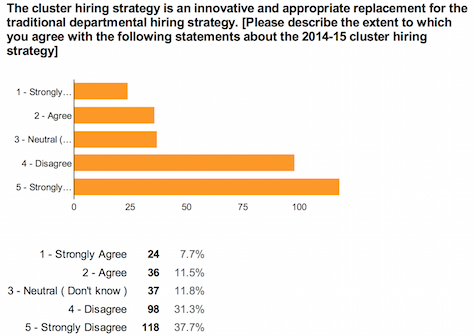

Perhaps most importantly, the overwhelming majority of respondents -- 69 percent -- disagreed (over half of them strongly) that the cluster-hiring strategy “is an innovative and appropriate replacement for the traditional departmental hiring strategy.” Most said their own departments’ hiring strategies were inconsistent with the cluster strategy; over half said the cluster strategy interfered with their departments’ strategies.

Less than one-third of respondents (29 percent) agreed or strongly agreed that the cluster strategy was likely to raise Riverside’s profile. Respondents were divided (though the largest proportion of respondents -- 36 percent -- was neutral) as to whether the initiative was likely to attract high-quality professors.

Such findings were fleshed out in the survey’s narrative section, which yielded more than 170 comments -- most of them negative. Many comments were supportive of cluster hiring in general but said Riverside’s initiative was too big and too haphazard to yield meaningful results.

“The cluster-hiring process is a true disaster for our university,” wrote one faculty member, suggesting that a much smaller initiative of 10 to 20 percent of overall hires would have been better. “It is destroying our disciplines and it is unprecedented in the U.S. (among reputable universities. [Riverside] will becoming the laughingstock [of] all U.S. [academia] when it will be realized that so much potential and so many resources have been wasted on such a foolish project. The process is pitting field against field, is pushing people to pretend that they will work in collaborative ways with other fields when this is not the case, and is undermining our core disciplines (for which no hiring plan B has been proposed).”

Another faculty member wrote, “The cluster-hiring process is a mess: by disempowering departments, it also disempowers faculty -- and creates enormous bureaucracy and procedural problems. My department makes each and every hire with tremendous care; now we have committees trying to hire four to eight people in less than a year! Stunningly stupid.”

Similarly, a professor of psychology wrote that a cluster-hire program could lead to innovation, but that the Riverside process seemed to ignore carefully crafted departmental growth plans. A professor of chemistry wrote that that department had been “systematically” excluded in the cluster selection process, despite being one of the strongest research departments on campus, and another respondent said clusters appeared to be chosen based how good they looked on paper, not necessarily their potential for success. One other professor said the approved clusters thus far seemed to ignore key issues, such as energy (although there is a group of clusters dedicated to renewable energy, those clusters selected so far are multiphase atmospheric chemical transformations, environmental toxicology and air quality in relation to health).

Some professors expressed concern that the clusters selected seemed to favor the science, technology, engineering and math fields -- a common criticism of cluster-hiring initiative and grand challenges-oriented research. "It appears that the cluster hires largely bypassed [the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences]," one respondent wrote. "There is also an impression that they focused on hiring people that can obtain grants, which again largely rules out" the college. Indeed, only a handful of accepted proposals were pitched by groups of faculty members primarily from that college.

One telling comment came from a faculty member who claimed to have been on one of two boards that evaluated the cluster proposals. The discussion was guided by administrators based on questions such as “Can you give me input on that?” rather than following any plan, the comment reads. “A clear challenge was that faculty on the board were overall relatively successful and from successful departments, so they were conflicted in voting for proposals from successful faculty (like themselves)/departments (they are members of). The results were often haphazard.”

Jose Wudka, a professor of physics and chair of the Academic Senate at Riverside, said the survey results generally communicate “support for the idea and goals of the program, but concerns about its implementation.” Concerns about the program in relation to standard hiring practices based on long-range visions for departments and individual colleges also are clear, he said -- specifically “that the latter would be starved to support the former.”

Wudka said the senate is working on recommendations that will be discussed by its executive council. The intent, he said, is “to provide constructive feedback aimed at improving the program and its likelihood of it being successful.”

D’Anieri, the provost, said in a statement that Riverside is “very excited” about the initiative.

“We believe that cluster hiring will help us to further diversify one of the country’s most diverse research universities, and will help to build new areas of strength,” he said. “Obviously, any program as innovative as this will spur some opposition, and we welcome good suggestions about this novel process.”

Laura Severin, professor of English and interim director of first-year writing at North Carolina State University, was involved in what is largely considered a successful cluster-hiring initiative on that campus. She said that many universities don’t understand that cluster hiring is a “tricky business that must be implemented carefully or it can easily fail.” Based on the Riverside survey, it seemed several mistakes were made, including not sufficiently engaging the “faculty imagination” in the process. In other words, she said, it seems professors “did not understand how this process could create a more exciting and productive work environment for those already on the faculty.”

In another apparent mistake -- and one that seemed to generate the most negative comments -- cluster hiring appears to have supplanted, rather than enhanced, traditional departmental hiring, Severin said. “Leadership needs to continue to hire in the disciplines, and make it clear to the faculty that disciplinary hires are still valued.”

Addressing several comments in which faculty members claimed that facilities they needed for their clusters were not yet ready for use, or in some cases, not even built, Severin said the “way forward” had not been adequately prepared. Communication also seemed to be a problem, she added.

“A good cluster-hiring program requires much planning and ongoing support from the highest levels of leadership,” Severin said. “Those who understand the issues surrounding interdisciplinarity need to be troubleshooting every step of the way, or the program will most likely fail.”

Severin recommended anyone considering a cluster-hiring program read a 2015 report from Urban Universities for HEALTH. While the paper focuses on how cluster hires can increase faculty diversity, she said, it’s also a good general introduction.

The leader author of that report, Susan D. Phillips, former senior vice president for academic affairs at State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and vice president for strategic partnerships at SUNY Albany, declined comment on the Riverside initiative specifically. That's in part because the initiative is still under way -- professors are only now being hired.

Generally, she said, her study of successful cluster hires suggested that “early buy-in from department and decanal leadership was critical, as was engagement and leadership of faculty.” That’s even if administrators have the final say. Another best practice for any initiative is clear and consistent communication during all phases of development and implementation, she said, quoting from the study.

“The anticipated benefits of cluster hiring need to be emphasized during the buy-in phase, when marketing the program to deans,” the study says. “Those submitting proposals for clusters need clear guidelines in advance. New hires need to know what their expectations are, and how activities related to the cluster will be integrated into the tenure and promotion process.”