The concept of manifest destiny began to show cracks the day Lt Col George A Custer met his end at Little Bighorn, outnumbered by Lakota Sioux and other warriors by an estimated 10 to one. Like all self-deluding notions, both he and it were bound to fail, and did so on an operatic scale. Walt Whitman wrote of Custer’s tawny flowing hair in battle, despite the fact he had shorn his famous locks days earlier in preparation for what he knew would be a bloody campaign.

“Now ending well in death the splendid fever of thy deeds, (I bring no dirge for it or thee, I bring a glad triumphal sonnet,) Desperate and glorious, aye in defeat most desperate, most glorious,” continues Whitman in his 1876 poem, From Far Dakota’s Canyons, written in faraway Brooklyn. The reality at Little Bighorn was somewhat different.

Custer planned to ride into the village and hold women and children hostage as a negotiating tactic. “Human shields might not be the best analogy,” explains Stanford professor Scott Sagan. “They were human shields in the sense of potentially protecting the soldiers, but were also a magnet that would force the warriors to stay put and defend the village.”

Sagan, a professor of political science who is widely published on issues related to nuclear arms, was drawn to this particular area of study for several reasons, principal of which are a series of 12 drawings made by an eyewitness to the historic conflict. Red Horse: Drawings of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, on display at the university’s Cantor Arts Center through 9 May, offers a rare chance to see first-hand accounts from a Native American perspective.

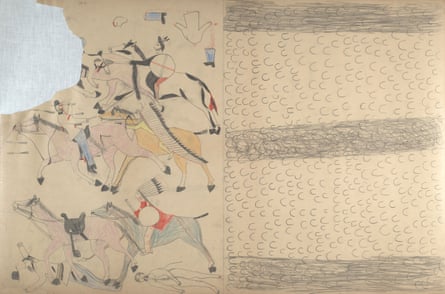

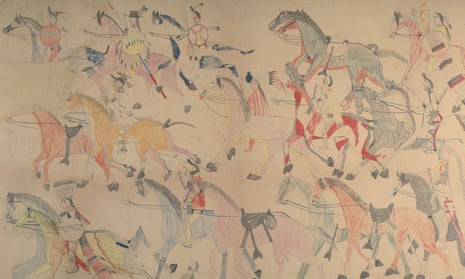

Red Horse was a warrior of the Minneconjou Lakota Sioux and a respected artist. He made his drawings in 1881, five years after the battle, as part of his testimony about Little Bighorn. The 12 pictures are on loan from the Smithsonian, where 42 works by the Native American artist were last exhibited in 1976 to commemorate the centennial of Little Bighorn.

Images include Custer comrade General Marcus Reno’s initial attacks on the village as well as Custer’s forces in battle on a hillside. There is a graphic portrayal of Native American casualties in addition to a field of dead horses, and combatants from both sides leaving the battlefield.

“These candid pictures show the reality of warfare at the time, but also Red Horse’s efforts to show the heroism of his friends, his fellow warriors,” notes Sagan. “So he shows them fighting hand-to-hand combat against what he viewed as the invaders from the United States.”

“What’s particularly fascinating about these is they’re so honest in the brutal depictions of warfare,” says Stanford undergrad Sarah Sadlier, who has ancestors that were at Little Bighorn and a great-great-uncle who may have been Red Horse’s translator. “In many ways Red Horse’s work is the most trustworthy sort of visual depiction we have of the battle of Little Bighorn, a Little Bighorn that’s not Custer-centric, one that nativizes from a participant who is a very respected person among the Lakota.”

A popular genre of the time, ledger drawing was new to Native Americans who previously drew on animal hides. Sagan compares the drawings to the Bayeux Tapestry, a depiction of the Norman invasion and one of the oldest representative historical documents also considered a work of art. Red Horse’s work is an ideal complement to The Face of the Battle, a popular sophomore seminar he teaches, in which students visit famous sites such as Little Bighorn and Gettysburg, assuming the roles of various historic participants based on research to help give them a combatant’s perspective of the conflict.

Although the conflict marked a rare victory for the Lakota Sioux, it was only a reprieve before a stronger push to put plains Indians on reservations. Red Horse’s drawings, along with an accompanying exhibit of student-curated Native American art on the subject, give voice to the victims of this barbarous treatment of indigenous peoples.

In his 2011 novel, Our Kind of Traitor, John Le Carre wrote: “The sacrifice of a brave man cannot be justified by the pursuit of an unjust war,” words that ring truer than Whitman’s eloquent, though misguided lionization of Custer in his poem.

“The portrayal of him has been one of gallantry, charging in a heroic last stand,” says Sadlier, who hopes the exhibition might debunk a myth or two. “What people need to understand is the impact of his devastating tactics against women and children, completely against the rules of war. I think it’s very important people be aware of that. This is one little crack in the facade that’s been created around Lt Col Custer.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion