Through the eyes of women artists, motherhood is increasingly a subject of contemporary art. For the Argentine-born artist Ana Alvarez-Errecalde, motherhood was the very impetus for becoming a contemporary artist. Alvarez-Errecalde’s searing photographs depict experiences like home birth, breastfeeding, care for a special needs child, and gestational loss. Drawing on the traditional trope of classic portraiture, and often taken outdoors or against a white backdrop, her staged images balance the wild and unknown—the blood and pain of bodily cycles—with the sensitivity and tenderness of human connection. Straightforward, tender, and often messy, her work is a response to popular media depictions of motherhood as immaculate or sexy.

Alvarez-Errecalde’s self-directed images of motherhood present a counter archetype of the mother: a woman in control and unapologetic about the gore, discomfort, and trauma involved in bringing a new life into the world. In an interview with Flic Magazine, Alvarez-Errecalde said, “I don’t think we have to get rid of one thing for the other. The problem that I see is that we only have this singular story being told and I think we have to be as plural as possible. Most of the popular imagery that we see of women comes from a male, heterosexual, occidental, and patriarchal perspective.”

Alvarez-Errecalde grew up in Bahía Blanca, Argentina and began her career in television, working as a producer for a TV channel based in Buenos Aires. After receiving a film production grant for minorities from Third World Newsreel, she moved to New York City and continued working in short documentary film production. While in New York, she met her husband, the artist Jorge Rodríguez-Gerada.

It wasn’t until the arrival of her first child, who was born with a severe neurological condition in 1999, that she turned to photography as a way to document how monumentally her life had changed. Her infant son’s acute physical and developmental needs and necessary therapy overwhelmed what she already felt was an isolated experience of motherhood, far from loved ones. Since most of her friends were in their early 20s and not yet parents (let alone a parent of a special needs child), few in her social circle could offer support.

Photographing her son was a way to share time with him, creatively and outside the rigor of therapy. “While I was photographing him, everything was perfect, there was nothing to ‘fix,’” she says. The photographs taken during his first year, and later when he was 14 and 15, celebrate her son’s beauty and the challenge of his condition. In her 2002 work Icarus at Home, she shows his body in repose, his underdeveloped arms and legs carefully folded, and his torso delicately wrapped in string, which secures the wings he is wearing. “I came to the realization that no matter how many ‘great’ programs I followed to make him more able, my ambitions were not his ambitions,” Alvarez-Errecalde said of the work in a 2014 interview with Hip Mama Magazine. “The situation reminded me of the myth of Icarus where Icarus’ purpose was not the same as his father’s, who built him wings in order to save him.”

Eventually the family moved to Spain, where Alvarez-Errecalde now lives with her husband and three children, and where she has established her artistic career. There she began shooting self-portraits and photographing other personal situations that she felt were underrepresented in contemporary art.

Alvarez-Errecalde’s work includes photography, video, and installations, and often features vivid depictions of the nude female body. For the show More Store, she displayed life-size nude “suits” of female bodies, from ages 18 to 75, hung like clothing in a boutique, their imperfections and stretch marks recalling details on a dress. Confronting the sexualization of female bodies, she presents them as harbingers of unique lives, each with its own story.

Her work is currently included in a traveling group show, Crítica de la Razón Migrante (Critique of the Migrant Reason) which has traveled throughout the Spanish-speaking word: The Casa de Encendida in Madrid (Spain), The Centro Juan de Salazar in Asunción (Paraguay), the Centro Cultural de España in Tegucigalpa (Honduras) and opened in Mexico City at Cooperación Española Cultura Mexico on January 19. Her work also appears in two English-language books about art published last year: Probing the Skin: Cultural Representations of Our Contact Zone (January, 2015) by editors Caroline Rosenthal and Dirk Vanderbeke and The Superhero Costume: Identity and Disguise in Fact and Fiction (Dress, Body, Culture) (November, 2015) by Barbara Brownie and Danny Graydon, which features the photograph Symbiosis from her series The Four Seasons 2013-2014.

We conducted our interview through email and later by Skype, during which Alvarez-Errecalde graciously answered my questions at 11 p.m. her time in Barcelona, while her youngest son peeked in on our conversation. She spoke directly and eloquently about herself and her career.

—Bryony Angell for Guernica

Guernica: How did your identity as an artist begin?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: I became an artist when I became a mother. My first son was born with a severe neurological condition and with that I saw all of my certainties crash around me. My husband and I were living in New York City at the time, far away from friends and family, and I was spending a lot of time caring for my son and trying to do a very exhausting early intervention program. Everything was so overwhelming and I was feeling so lonely that I started taking photographs as a way to cope. I needed to focus on the beauty and unique presence of my son regardless of his challenges.

Guernica: What is your process for creating art?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: The process is different every time, there is no template. Sometimes while doing something completely ordinary like bathing my children or driving, I come up with a thought that stays in my mind. Other times it can be a conversation with my wonderful husband or my friends, or I might have an image in my mind inspired by a specific place or person or a recurrent dream. I transform these thoughts and dialogues into images to reach a broader audience.

Guernica: Some of your most arresting images are Birth of My Daughter and those in The Four Seasons series, which depict motherhood in ways that challenge the conventional mother/child imagery. How did you conceive of these images?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: I took the photographs for El Nacimiento de mi Hija (Birth of my Daughter, 2005) because I had a profound need to see this sort of maternity represented. While I was pregnant with my daughter, every time I would close my eyes to go to sleep, I had this recurring image of being connected to my baby by the umbilical cord. When I took these photographs it wasn’t my intention to include them as part of my artistic work.

I soon understood that these photographs had a universal importance that transcended the personal documentation of my experience.

Guernica: So you prepared to take these photos immediately after the home birth of your daughter?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: I didn’t know if the home birth would allow me to capture these moments, I just wanted to do my best to create an image like the one that had enchanted me in my mind. When I saw the contact sheet (at that time I was still shooting film) I soon understood that these photographs had a universal importance that transcended the personal documentation of my experience. I was healthy, happy, and lucid to the extent of being able to do a self-portrait! I felt that these photographs could help others rethink the idea of the fragile, painful, out of control, and overly medicated birth that is considered the norm.

The births performed in movies or television tend to make the woman into a spectator, the baby into a product, and the doctor into a hero. A home birth like mine subverts the order completely. The mother is the hero, the baby is the motivation that gives meaning to the experience, and the doctor or the figure that represents him—a midwife, husband, etc.—is a mere spectator who accompanies according to the woman’s needs. A birth like this one is subversive and at the same time it’s a metaphor in the sense that it goes beyond the occurrence to delve into deeper issues of our understanding of society, fear, and life.

Guernica: The Four Seasons can be viewed together or individually; each one is so distinct.

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: Las Cuatro Estaciones (The Four Seasons, 2013-2014) is a series of photographs based on my experience of mothering three children and having a late gestational loss. Each image was inspired by different circumstances.

Annunciation (The Four Seasons, 2013-2014) is a self-portrait with my eldest son. I portray unconditional love, a bittersweet love that can inspire and devastate while we commit to accompany the destiny of another human being. I have seen myself holding my son’s body so many times, with an attitude that reminded me of La Pietà by Michelangelo, and I reflected upon the contradictory feelings that are provoked by seeing a little boy growing up and still being completely dependent on his parents. That is how Annunciation was conceived.

Guernica: What circumstances inspired the photo with your daughter?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: Shadow (The Four Seasons, 2013-2014) is a self-portrait with my daughter, and represents the mother wolf who is capable of ferociously defending her offspring as well as imposing fear, repression, and limits on them. It was inspired by a conversation with a close friend. She was suggesting my daughter could ride her bike alone in the countryside and I was telling her about the reasons why I could not allow her to do so by herself. Being aware of my own fears, having to come to terms with the freedom I would like to guarantee while at the same time feeling obliged to either repress or put her at risk, triggered this image in my mind.

Guernica: The Four Seasons addresses each of your children, including the one you lost late in term?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: Yes. Assent (The Four Seasons, 2013-2014) is based on a late gestational loss and is about trust and letting go—detaching oneself from expectations, wishes, and demands. I treasure that experience and the sense of calm, trust, and reconnection with an innate wisdom that it gave me.

Guernica: One of your Four Seasons images is both playful and provocative, showing you and your youngest child in costume, you wearing the mask portion of his superhero costume and his arm concealing your breasts.

It is not about being a “supermom.” It is about two complete beings that strengthen each other by the relationship they establish. That is where the mutual empowerment resides.

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: Symbiosis (The Four Seasons, 2013-2014) talks about relationships that nourish each other both physically and psychologically. It challenges the idea of a negated mother who also negates her body and her presence to her children, so they will all ultimately conform to our unattended, unloved, and unnourished society. It is not about being a “supermom.” It is about two complete beings that strengthen each other by the relationship they establish. That is where the mutual empowerment resides. It was created while breastfeeding my child one summer evening. He was starting to wean himself and was running around in his Spiderman costume. At this casual moment, I contemplated the powerful repercussions that our bond manifests and will continue to manifest in our lives. I decided to put the mask on too. Between the two of us, we complete a primal super identity.

Guernica: How does your early career as a documentary filmmaker influence your work?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: I think I am still documenting stories. Before I was focusing on other people’s stories and now I am documenting my own. I was working in Buenos Aires for a TV channel as a producer for a show, which would talk about art and events in the city. A grant from Third World Newsreel was what got me to New York. It was a grant for minorities in New York, which allowed me to produce a few shorts. Later, I worked for independent producers who would then sell to PBS or other arts organizations. After becoming a mother I realized I also had a story to tell.

Guernica: How do you feel your message of motherhood differs from other images of motherhood in contemporary art?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: In my case, letting my mothering experience permeate in my artwork makes me vulnerable to other people’s judgments and preconceptions. I have been criticized for exposing the intimate moment of birth and for breastfeeding an older child. The fact that I show the blood of birthing or menstruating is sometimes compared to the vulgarity of photographing someone defecating. I am not offended by these comments because I know it is an indicator of the lack of respect there is towards women’s bodies in general, and it brings to light a more alarming issue: the little value that as a society we give to birth, breastfeeding, infancy, and caring for people in need.

Guernica: Becoming a mother clearly empowered you to share your experience of injustice.

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: Motherhood intrigues me and inspires me because in our western society it is being idealized and punished at the same time. [Societal] admiration and judgment is rooted in the general objectification of women.

We can see all sorts of artwork—om paintings to movies, from songs to poems—idealizing mothers. We have an incredible amount of advertising that gives incentive for women to have babies. Not to mention how the media glorifies the pregnant bellies of each movie star or model, and later their naked bodies with their offspring to sell magazines. But in reality, mothers have no support, mothers are lonely. We lack family and neighborhood networks. We lack the tribe that is needed to raise a child. Society shuts us out of the marketplace and almost forbids us to earn a decent living unless we comply to leave our babies in the hands of a monstrous system that does not cover the baby’s innate needs of breasts and arms, the exo-gestation needed by any immature mammal.

Mothers who choose to stay with their babies are said to be “blessed” by having the opportunity to raise them, but in reality it’s a courageous decision. And we paid a high price for it. By raising a child mostly by themselves, mostly within a diminishing economy, and mostly while having to cope with a socially devaluing judgment that tells mothers that by having a baby they just committed professional suicide.

And if you happen to have a child with any kind of disability it becomes even more severe. Like any other woman, mothers are judged, advised, directed. But ultimately, if they express themselves, if they decide by themselves, then they are punished. Mothers become invisible.

Guernica:You include your own mother in your artwork. How did your upbringing and her influence impact your artistic evolution?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: I have included both my mother and my father in my artwork. My parents impacted my creativity because they were supportive of their children’s diverse interests. It wasn’t always easy for them, that is what makes their support even more valuable.

The city I grew up in, Bahía Blanca, was very conventional, with a huge religious and military presence. My parents both worked, my mom was a teacher and my dad owned a perfume shop. I am the youngest of seven. We grew up in a house full of books. During the almost permanent economic crisis in Argentina, my mom managed to buy National Geographic magazines, and because of these I had an interest in anthropology and storytelling. Those magazines from my mother were a huge influence.

When I started developing my art career, my art was not the kind of art they could relate to. They couldn’t understand how I could show that (Birth of my Daughter). But they have not judged me. They understood the importance of telling the story and bringing awareness. It took a while for my father to feel proud, but I knew he was when he took my catalog to show his coffee shop friends—all in their eightiess—in Bahía Blanca!

When women are the ones that take care of and raise the children, it seems creativity is diminished by that, but it can be a source of power to add to creativity.

Guernica: How does your artistic work influence you as a mother?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: My artistic work does not influence me as a mother. It is the other way around. When women are the ones that take care of and raise the children, it seems creativity is diminished by that, but it can be a source of power to add to creativity. Childrearing and creativity are activities that are intertwined. You accommodate your needs to the child’s questions and you think creatively.

In Spanish I like the fact that the words “to create” (crear), “to raise children” (criar), and “to care for” (cuidar) are so similar. Creativity is exercised every time you are challenged and taken away from your comfort zone: Kids are great masters.

Guernica: You and your husband include your children in your artistic life. They are in your work, they travel with you to your shows.

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: Including the kids in our life happened organically. We want to be the ones caring for our kids and the fact that we are both artists, we talk about art, we create art, it becomes very natural. When my eldest son was 12, one festival assistant where I was exhibiting asked me, “You have never been away from your children in 12 years?” I hadn’t realized, up till then!

Of course we go out once in a while as a couple, but if we have to mount an exhibition, what is a better stimuli or learning experience for a child than being part of your parents’ life and daily jobs? Kids want to learn from real life and like to collaborate and feel that they are valuable.

Guernica: How has the arts community and market supported you as an artist and mother?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: The arts community and market has offered very little support. I have submitted a few of my projects to open calls where they would get some funding but curiously enough all the money had to be spent on the art production. So there is never money left for personal and family needs. My immediate community (which lately is mostly online) supports my art by giving visibility to what I do and by taking part in my projects. Over the years, with a broader recognition of my artwork, I am starting to participate in art festivals and exhibitions that have given their support not only economically but also logistically.

Two art shows covered the stay for our whole family: City of Women in Ljubljana, Slovenia and Extravagant Festival in Zagreb, Croatia. I told the organizers that I travel with my family, with a child in a wheelchair. It’s important to say that this is what I do, I travel with my family, this is part of my activism as a mother/artist, and the organizations understood this. It’s one thing if women are saying this, but men need to say this as well. My husband also does it.

Guernica: Are your images meant to be confrontational? What response do you expect from viewers?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: I assume that each viewer comes with different cultural, social, and personal emotional baggage. I do not create the artwork with a specific confrontational purpose. The images can confront the viewer with their own most profound fears and with their ingrained religious and/or technocratic beliefs.

I want to challenge the preconceived ideas that make young girls believe that menstruation has to be painful and that they should be ashamed if someone notices that they are bleeding. I want to tell men and boys that being supportive of the autonomy and strength that women are able to experience can only make our bonds stronger, more meaningful, and more sacred.

I want to tell pregnant women that birth, with its intrinsic demands that pushes our physical and mental boundaries, can be an absolutely transformative path, very pleasurable and worth being experienced to the fullest. Medicine and pharmaceutical interests have made a pathology of every normal and physiological process. If we are healthy, we can trust ourselves and an ancient design perfected by evolution to know that our bodies are doing exactly what they need to do. That our babies are asking for exactly for what they need in order to grow happy and healthy: arms and breasts. Love and being part of our daily active lives, instead of being left for hours with substitute mothers such as nurseries or TVs, tablets, phones, and screens that isolate them from nature and human interactions.

Guernica: Some of your work addresses migration. How has your experience as a migrant to the United States and Spain impacted your art?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: More Store (2008) and DSD, Islas Migrantes (DSD, Migrant Islands, 2010) are two projects addressing migration. I have experienced migration both in the US and in Spain, always as a young, white, South American woman. I have experienced underpaid jobs, abuse of power from Immigration officers, and submission to absurd laws that are against the basic human right of freedom and equality. But I was lucky enough not to experience prejudice or persecution as some other migrants who are often conditioned by their place of origin and/or skin color. I did not have to migrate due to war, or experience the impossibility of returning home. In a way I was a privileged migrant but I also suffered the injustice of an inhumane system.

Working with migrants from different origins allowed me to portray a broader reality while capturing the essence of a system which keeps feeding itself by generating poverty in many countries around the world, advertising the extravagance and abundance of others and subjugating the people that, due to lack of opportunities, wars, or other types of violence, see themselves obliged to leave their homeland.

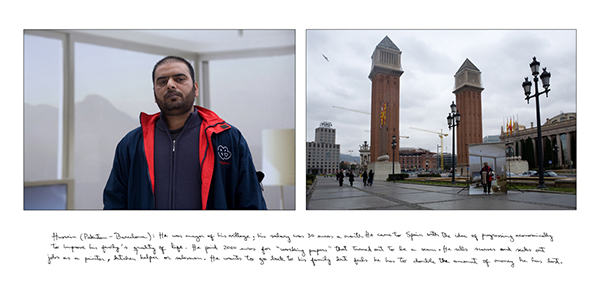

DSD, Migrant Islands is a photographic project that utilizes a concept used in antique studio photos, where people would have portraits taken against an idyllic backdrop to be able to have a memory for family and friends that projected a dignified, prosperous, and happy life.

To realize DSD, Migrant Islands, I interviewed immigrants coming from diverse countries in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, and Latin America that look for a way to survive with pseudo-jobs on the streets of Barcelona: like selling knock off products, pirated music and videos on bed sheets laid out on the sidewalk, beer cans, samosas, flowers, jewelry, and domestic help. Based on these interviews I created backdrops that were a modern take of the idyllic backdrops used in the past and photographed each immigrant protagonist in two distinctive compositions.

Guernica: Your past work has been in response to personal experience. What are you responding to now in your work?

Ana Alvarez-Errecalde: I want to continue to expand the constrained social imagery regarding motherhood, parenting, vital cycles, and aging. I also want to question attitudes that encourage us to delegate responsibility to others. Our freedom is proportional to the responsibilities we are able to assume.

To contact Guernica or Author Name, please write here.