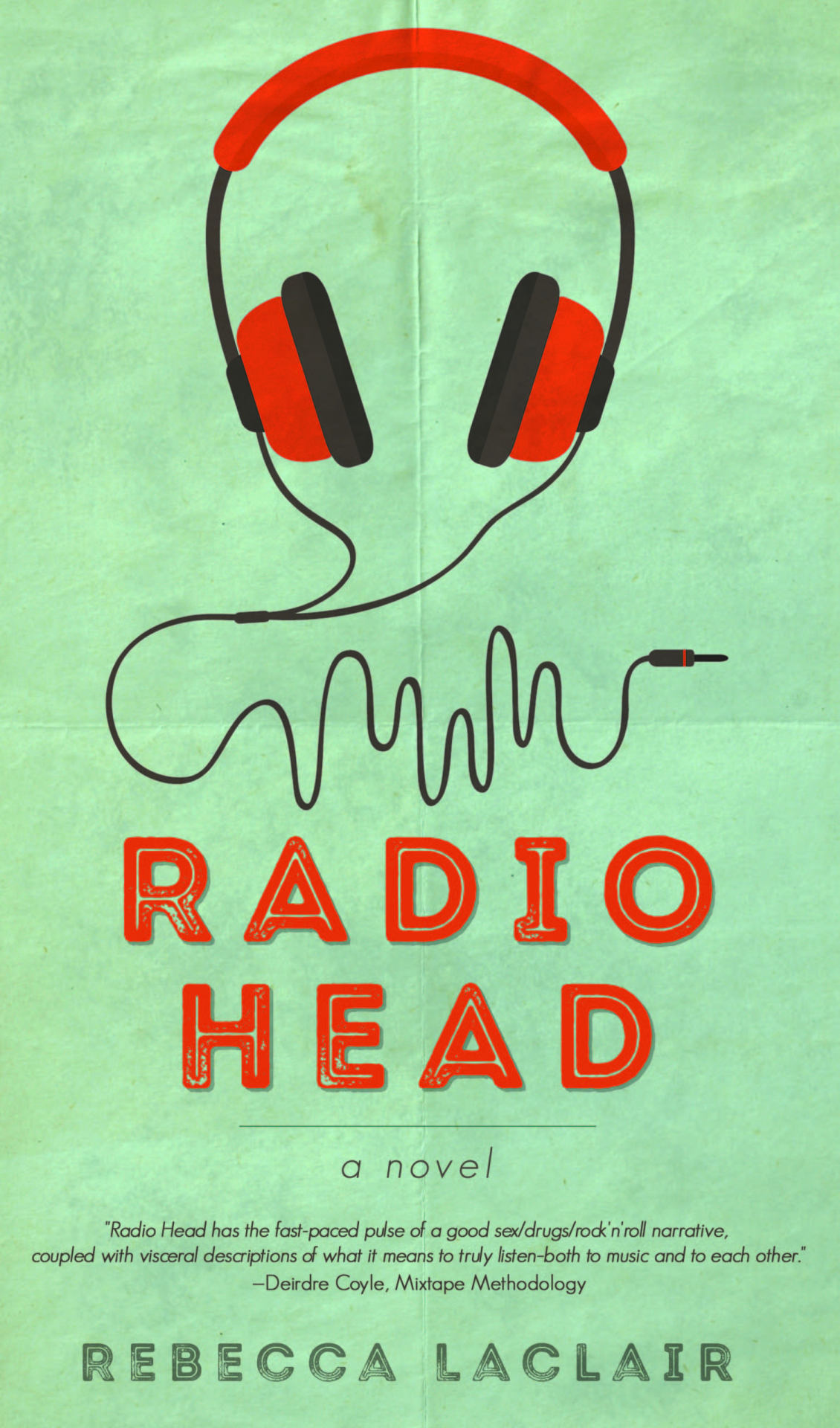

Radio Head (Excerpt)

CHAPTER ONE

Shelby

White-coats say I’m crazy.

I never met anyone else who can do it, get an earful of everything that makes up a person just by touching them. It’s a one-sided conversation, a blind confessional, listening to a stranger who can’t hear me. And lonely.

Music is my only friend. How’s that for crazy?

The westbound bus going under the freeway and into Laguna Beach is a good long ride. Three full loops should fill the time until Mom goes to her night shift.

I dump my backpack in the next seat to block anyone from sitting there and put my headphones on. Out the window, the early morning traffic rushes to change lanes. I wish I had somewhere to go. I can’t stay at Mom’s apartment much longer. When I was little, I thought I’d enlist like Daddy. We always had a decent place to live and food to eat. And we moved a lot, which I really liked. It seemed we were able to pick up and leave just when the county social worker got wind of my bruises, the kind a kid gets when her parents are falling down drunk or when one finds out the other is getting a little side action.

I try to ignore the noises from my stomach. There isn’t much to pick from at the apartment. A lot of things don’t agree with me anyway, but I don’t find out until my tummy starts that deep ache, a sharp stab right in my center.

We lumber on through traffic, lurching occasionally to a stop. New passengers shuffle on, an immigrant mother pushing a baby stroller loaded with groceries, surrounded by two silent children not yet old enough for school, and an older lady in a maid’s uniform, clutching a lunch box. The women are careful not to meet each other’s gaze yet they both scowl at me. Next on, a guy with a 12-pack in a grocery bag who eyes me hopefully. I hate Mom’s clothes. Between the silver tunic and the heels—too big, and too high—they probably think I’m either hooking or on my way to dance at Mom’s club. I swear I never will. The manager tells me no one will ever pay me as much as I could make dancing. This sniffs of a lie. Seems to me it’s Mom who pays to dance. Maybe not in cold, hard cash, but she’s definitely paying something cold and hard.

I thumb the dial on my radio and close my eyes, rolling the tuner back and forth, dusting the last few specks off a station that plays music without words, by people with extraordinary names like Tchaikovsky and Haydn. Their music fills me more than I can bear, saturating and stretching me from the inside, like when I think about what happened to Dad, or that time when I threw up and the school nurse stroked her fingers in my tangled hair for almost an hour. She wasn’t mad, and she didn’t wish I would just go away.

They call it “classical,” which cracks me up, because the instruments and melodies sound so unlike the other classical stations: Classic ‘80s, Classic Rock, and Classic Oldies. Sometimes static interference becomes the DJ, broadcasting stations at the radio frequency’s whim. But it has to be music. Any music. I don’t listen to people talking, talking, talking about stuff that happened to someone somewhere, or the weather, or the Bible. I already know the story they’re going to tell because I hear it in music. Songs are all about those things, even when the lyrics aren’t. The rise and the fall of the tempo and the melody tell all the talkers’ stories of troubles, of triumphs, of people hurt or lost, or reunited. There’s nothing the talkers can say that the music hasn’t already told me.

As the bus edges closer to the coast, I people-watch for a half-dozen stops or so. There is a change to the mood of the passengers the closer we get to the beach. The listless stares at the scuffed, black-matted floor become far-off glances out the window into the salted, marine air. Conversations shift to plans for the weekend, excitement grows. There is buoyant hope for the possibility of fun.

A couple squeezes up the steps of the bus, hip crushed against hip in the narrow entrance. The only double seats available are next to me. I turn my gaze away as they approach, whispers toppling one another as they exchange ideas for how best to spend a day by the water. I can almost feel the warmth of their regard for one another when I realize I’ve been holding my breath, longing for my own connection, a hand to hold mine that won’t let go.

“You mind?” the woman asks, standing over me. I pull my backpack into my lap and she plops down, her thigh wedged tightly against mine. Through her touch I can hear her, the song she holds inside, the rhythm of her selfish assumption, “If no one finds out, no one gets hurt.”

They’re cheaters. Truants, I can tell. Escapees from marriages no longer joined at the hip.

I replace my headphones to my ears and turn up the volume, singing to myself to drown her out, and stare hard at the asphalt scudding by below. I need to keep moving forward. When I get some money I’m moving away. Old enough to live on my own, Mom says.

I wish Dad was still around; he’d point me in the right direction. I figure it’s no coincidence that all I have left of him is his old AM/FM radio. I think he meant for me to have it.

Maybe he’d put back a few too many, but he told me he bought it for my grandma, who passed around the time I was born. “She really got into pop and electronic music back in the early ‘80s,” he said, a far-away admiration warming his drawn face. “She just wanted to dance.” He didn’t sleep for several days; the radio exhumed a glimmer of the boy he used to be, held him afloat a while. Like a stupid kid I told him he should have gotten an MP3 player so he could load Grandma’s favorite songs. He shook his head, a dense load of nostalgia weighting the simple gesture. “You got to tune in to the pulse of the moment. It’s a chance encounter, Shelby, that’s what she used to say.”

There is a sudden sting where a few caught strands of my hair are yanked from my head. My music is stripped away in one motion, like pulling a Bandaid left too long over a wound. I gasp and cover my ears where my father’s headphones should be.

CHAPTER TWO

Zac

A stout guy with a nearly indiscernible neck leans over the high counter to chat up Dr. Gibson’s receptionist. One thing about LA, every damn front desk girl could pass for a model, a freak phenomenon I binged on when I first moved here.

Lots of girls offer “you-get-what-you-pay-for” hook-ups, fun and done. Good genes will get you so far, but as aphrodisiacs go, cash and publicity incite an inelegant madness. I get it, every conquest is a stepping stone. But there’s always another guy, richer and more famous than me. They say no one walks in LA. Truth is, no one settles in LA. I’m glad I figured that out fast and hooked up with Ashtynn Kingston.

The waiting room’s carved wood door swings open and the guy at the counter swirls his stocky body away from the receptionist. I glance up, surprised to see Dr. Gibson stroll through carrying a cardboard tray with four coffee cups. He was Ashtynn’s doctor when she O.D.’d. It was only eighteen months ago, but I barely remember him, like a distant uncle or second-cousin I met once at a family reunion.

It’s one thing to make me sweat it out in his waiting room, but showing up late? Who’s the rock star here, bud?

“Coffee boy this morning, eh, Roland?” the guy teases him.

I begin to reach for my phone to text my manager, Berger, about Gibson rolling in late, but freeze. Dumping me in the lap of some shrink who doesn’t give a crap looks a lot like step one in a not-so-covert plan to finish me.

Dr. Gibson grabs my frozen hand and shakes it. “Good morning, Mr. Wyatt. Nice to see you again. I look forward to working with you.”

I shake his hand and size him up, searching for sincerity behind his veneered smile.

Gibson turns and nods to the other guy and the receptionist, “Zac Wyatt, I’d like to introduce you to Dr. Elliott Rachman, and our assistant, Carly.”

That burly dude is Elliott Rachman? The so-called, “Counsel-ebrity,” and director of this practice? I’d always wondered why Ashtynn didn’t choose him as her therapist. Now I get why she picked Roland Gibson. He’s the PR-friendly pretty-boy.

“Take my word for it, Roland’s all about serving his flock,” Elliott says with a wink. “Just be glad it’s only coffee. He might offer to wash your feet.”

I appreciate Rachman taking a few jabs at the man who’s got my balls and my future at the mercy of his professional opinion. Gibson thinks he’s Jesus, that’s funny.

“It’s an Americano,” Gibson says, handing me a coffee. Rachman grabs his own from the tray, takes a sip and winces.

“That was Carly’s chai tea. It wasn’t your mocha.”

Rachman spits the tea back in and hands it to Carly, grabbing the last cup. He adds three packets of sugar and works the stir stick like he’s already had his share of caffeine. Yeah, Rachman would make Ashtynn barf.

Gibson places his hand on my shoulder and asks me to join him in his office. Anxious to get on with it, I follow him in, sliding into a broad leather chair. He closes the door and takes his seat behind a heavy, polished desk, big enough to garage a vintage convertible.

I stroke the side of my chair, reclaimed leather, and swivel to face the floor-to-ceiling abstract art installations behind him. Fuck, now I’m getting a little worried. Is he going to ask me what I see in them, like some lame Rorschach test? How do you pass one of those things?

Folding his hands, Gibson takes a deep breath and closes his eyes. Keeping them lightly shut, he starts to speak. To himself.

“I immediately release all thoughts belonging outside this room, and allow any judgments I may have to drift away,” he breathes. “I provide an open, safe environment for growth. I am ready to listen. I—”

“This is bullshit,” I say, shaking my head.

Gibson’s eyes open leisurely, not the least disturbed by my interruption.

“Let’s get one thing straight right now. I’m here because I have to put on an act for all my fans who’re afraid I might fall from grace. Ooh, drugs are bad.”

I need to chill, I’m getting ahead of myself.

Changing gears, I level with him: “I don’t have a drug problem. I can pretend to get past one for the public if you want to play that scene, but the truth is I’m no fucking junkie.”

Gibson says nothing for a moment, then surprises me with a grin. “It must be easy for scouts to spot raw talent. They just look for the person who is, for no one reason, larger than life. Certain people fill the room with an energy and light the average individual simply cannot muster.”

Rising from his chair, Gibson walks around to the front of his desk and leans against it, only inches from me. “We’re all observers of people, students of the human condition, aren’t we, Zac? It’s how we navigate the social arena, and realize the truth of ourselves—within the context of our interactions.”

“You of all people, a shrink, shouldn’t judge a book by its cover.”

Gibson lets out a big, hearty laugh. I’m glad one of us thinks this is a good old party.

“Nearly everyone who walks through my door issues the ‘Non-Junkie Declaration,’ Zac.” He is quiet for a moment, then adds, “More than 4.6 million people in America meet the criteria for needing treatment, but don’t recognize they have a problem.”

I shift in my seat, contemplating whether to walk out. I’m not a junkie. It was nothing, just one fucking time. I still have bad dreams about the hospital, the night Ashtynn went into ER. Gibson was there, he ought to understand that I get it. I get what can happen.

What if I walk out, tell this fucker I don’t need him, that I don’t belong in rehab? Everyone forgives our guitarist, Stanford. Getting wasted is just part of his persona, his goddamn brand. There is no forgiveness for Zac Wyatt, no way. I’ve got to play along until the whole miserable episode blows over and is forgotten. You want to play, Doc?

I turn it on, gazing at him with what Amp’dTeen mag called, “Silvery turquoise eyes crackling with life and lust and liquid hope,” a far cry from the lifeless stare of some random heroin addict.

“All my rehab patients are required to submit to a physical and blood test, and your evaluations are scheduled for this afternoon. It’s standard protocol, Zac,” he continues. “Your skin tone, eye clarity, and healthy, muscular build support your assertion. But more importantly, I’m here to listen. You tell me what’s true and what isn’t. Let’s begin our partnership with a shared goal of trust. Are you with me?”

I don’t have much choice.

“Right on.” I grip Gibson’s outstretched hand in a loose cycle of gang-inspired handshakes. The old guy manages to keep up. His fingers are as smooth as Ashtynn’s.

Sliding into the matching leather seat next to me, Gibson doesn’t waste any time. “Why don’t you tell me how you landed here, then. What series of events lead to an entertainment attorney asking me to help rehabilitate you from drug use,” he asks. “Should be an interesting story.”

In fact it isn’t. My management prepared an official statement in rebuttal of the photo leak. I’m supposed to recount it verbatim. But I guess I should give him the unscripted version.

“There isn’t much to tell. Me and Stanford—”

“Stanford?”

Seriously? This guy hasn’t done any homework on me? “Stanford Lysandre, Grounder lead guitarist. Perhaps you’ve heard of him?”

“Of course. I only ask for clarification, and invite you to do the same, Zac.”

“Right. We were hanging with a group of girls—some fans of the band, you know—just kicking it at our producer’s place while he was in Munich, when Stan and one of the girls decided to do up.”

“Do up? You mean, inject diacetylmorphine intravenously?”

“Yes.” I hate having to talk about this. “Dude, c’mon.”

Better him than go to court. He motions me to continue.

“They were all into it, and I decided ‘what the hell.’ If I was worried about anything, it was about getting sick or shitting my pants.”

That would have been worlds better than the mess I’m in now with my management, my label, and my fan base. I’m not even speculating what my band might do about it.

“You were worried?”

“I’m pissed off. You’ve probably seen the photos–they’re on every website, and in every magazine. One of the girls took them with her phone, making I don’t know how many thousands of dollars without ever revealing her identity.” I inhale after that mouthful of words, and add, “That bugs the shit out of me, but damn if I can’t remember her name to call the sniper out.”

“So from your perspective, this is her fault?”

“Yeah!”

He doesn’t say a word in response.

“Well, not entirely,” I back-pedal. “I just fell under a negative influence,” I assure him, recalling the lingo of mandatory high school drug awareness programs. Exactly who that “negative influence” was shouldn’t require any stretch of Gibson’s imagination. Stanford is a notorious addict.

We’re both quiet. Gibson can wait for me to ‘fess up.

I need to take some control here. “You a music fan?”

“Yes, of course,” he says. “I’m a big fan of Ray LaMontagne. He’s from my hometown. I also dig Van Morrison, Jeff Buckley—” Gibson demonstrates his affinity for acoustic rock with an air guitar impression. Fuck, there ought to be a law against air guitar.

☊

Rebecca Laclair is author of the novel RADIO HEAD (February 12, 2016). She has published short stories and band interviews in Gravel, Wordhaus, and Mixtape Methodology. Get acquainted with her work at www.RadioHeadBook.com.

RADIO HEAD is now available for pre-order on Amazon! Click to pre-order where books are sold:

Amazon I Barnes & Noble I Books-a-Million I IndieBound I Amazon UK I Goodreads