Dementia

For Those With Alzheimer’s, a Place to Remember

Can we help people with dementia and Alzheimer’s recall their pasts?

Posted August 26, 2016

Alzheimer’s disease slowly and invariably steals a person’s past. But we may be able to create environments that help people remember. I recently visited a space designed to bring old memories to mind.

In Aarhus, Denmark, there is a museum called Den Gamle By (The Old Town). Buildings from different time periods are preserved in Den Gamle By; some date from hundreds of years in the past. Not only does the Old Town preserve old buildings, it is also a living history museum. Actors play the parts of people who lived and worked in different times. You can visit a variety of workshops and stores: a blacksmith, a shoemaker, a tailor, a merchant store from 1864, a bookstore from 1927, and an electronics shop from the 1970s. (That was cool.)

But one part of the museum isn’t open to the general public. Instead, these rooms are a special place for visitors with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. These rooms comprise the "reminiscence apartment."

Dorthe Berntsen, my colleague from Aarhus University’s Center on Autobiographical Memory Research, recently took me to visit the reminiscence apartment. We were met by Tove Mathiassen, the museum curator who designed the apartment and who leads the reminiscence project.

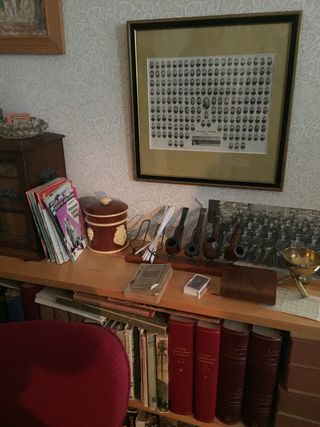

The reminiscence apartment is designed to be a small family home from the 1950s. You can see some pictures I took during my visit. Everything is historically accurate: the furniture, the kitchen and cooking utensils; the books and photos; the bedroom and bathroom; even the clothing in the closet, the sheets on the bed, and the beer in the pantry. During our visit, we had coffee and pastries just like what a family would have served visitors in 1954. The apartment is beautiful, and real.

Even though I’m not Danish and wasn’t alive in the 1950s, I found a sense of nostalgia coming over me occasionally. There were enough similarities with things from my parents’ and grandparents’ homes that I felt transported in time. But the apartment isn’t a perfect match to my American past. According to my Danish colleagues, the impact is stronger for Danes whose grandparents’ homes containing many of these articles.

And for Danes who were young adults in the 1950s, the reminiscence apartment is incredibly powerful. Unbidden memories bubble into awareness. Nostalgia overwhelms one’s emotional state – that warmth of awakening the past often accompanied by both a sense of longing and the realization that the 1950s cannot be completely revived.

The reminiscence apartment regularly hosts visits by individuals with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. When visitors arrive, they are invited to explore, open drawers, and handle everything. Eventually the visitors move to the table, sharing coffee and pastries just as my colleagues and I did. Afterwards, they move to the living room and sing songs from their youth. Every item and every experience helps to reinstate the 1950s.

In this fashion, every aspect of the visit cues the retrieval of memories. Smells and tastes can be powerful retrieval cues. Music induces nostalgia (as I noted in my post, Music-Evoked Nostalgia). As my colleague Dorthe Berntsen suggested to me – memories may lie hidden in places, objects, smells, tastes, and sounds. Seeing and handling the objects may pull long forgotten memories to mind.

The responses are beautiful. When elderly individuals with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease walk into the apartment, they are typically overjoyed. Tove Mathiassen described the reactions and I’ve also seen a video. Not only are people happy, but they also start remembering. Sometimes they share and describe general experiences from the time of their young adulthood. Often the setting, objects, smells, tastes, and sounds bring to mind particular events from decades of the past. When they leave after a two-hour visit, the dementia visitors are tired and happy.

In an experimental investigation, Dorthe Berntsen and her colleagues found the reminiscence apartment improved the retrieval of memories in individuals with dementia and Alzheimer’s (Miles, Fischer-Morgensen, Nielsen, Hermansen, & Berntsen, 2013). They presented objects as retrieval cues to a dozen older individuals with dementia. In the reminiscence apartment, they presented objects from the 1950s. In the individuals’ modern living locations, they presented matched objects from the current era. The respondents remembered more and provided richer narratives when they were in the reminiscence apartment. The apartment is clearly effective in bringing memories to mind—even and maybe especially for individuals suffering from dementia and Alzheimer’s disease.

Why is the reminiscence apartment so effective, both in helping memories return to people and in lifting mood? Clearly retrieval cues matter. The better the match between the current context and the context of the original event, the more likely autobiographical memories return to awareness. The impact of retrieval cues works for all of us, not just individuals with Alzheimer’s.

But the nature of remembering also matters. Sometimes we search for memories. We make a voluntary effort to remember something, whether it's an event, a piece of knowledge, or the location of our car keys. Voluntary remembering relies on effective cognitive control of mental activity. It is effortful and often hard. It may be particularly disrupted in dementia. Simply asking someone with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease about the past is unlikely to result in memories coming to mind. The information may remain with the person, but they are generally unsuccessful in trying to voluntarily retrieve the memories.

Other times we experience involuntary memories. Something around us reminds us of an event. We don’t search for a memory. Instead the memory finds us. The reminiscence apartment provides a perfect match to the Denmark of the 1950s. You don’t have to search for memories if you were a young adult then. The objects, tastes, smells, and sounds call the memories to mind. This form of remembering feels effortless and appears relatively spared in dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Involuntary memories don’t require effective cognitive control. They bring to mind emotions as part of the re-experiencing moment. Eventually, involuntary remembering will also be destroyed, but for a time, memories and emotions can emerge in response to a thoughtfully designed world.

The reminiscence apartment obviously provides lessons for constructing living situations and daily events for people with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Keeping some familiar objects from an earlier time period may provide more than simply comfort. Listening to old music may do more than create a sense of nostalgia. The smells and tastes may do more than bring to mind grandma’s kitchen on Christmas morning. For a period of time, the memories and emotions may also help restore the person.