[Editor’s Note: The following is an excerpt from Stacy Mitchell’s new book, Big-Box Swindle: The True Cost of Mega-Retailers and the Fight for America’s Independent Businesses (Beacon Press, 2006).]

Citizens groups are waging a growing number of successful campaigns against big-box retailers. They are winning victories in places as far-flung as Damariscotta, Maine, a coastal village where two stay-at-home moms ignited an uprising this past spring that not only blocked a Wal-Mart supercenter but led several towns to adopt store size cap laws that effectively ban big boxes region-wide, and Inglewood, California, a working class city near Los Angeles where voters handed Wal-Mart a stunning upset two years ago even though the chain spent over $1 million on a massive public relations blitz.

Despite differences in circumstances and demographics, all of these successful campaigns — and there have been dozens in the last two years — have one striking commonality: a core part of their strategy involves getting people to see themselves not just as consumers, but as workers, producers, business owners, citizens, and stewards of their community. When people walk into a voting booth or city council meeting with this vastly expanded sense of their own economic and political identity, they are far more likely to reject big-box development projects and to endorse measures that force these companies to adhere to higher standards. This is a crucial lesson as we work to knit these local efforts together into a broader movement to counter the power of global corporations.

In contrast, when the big chains win, they do so by getting people to assume the familiar and narrow role of consumer and to view their relentless expansion and radical restructuring of the economy as simply a matter of shopping options.

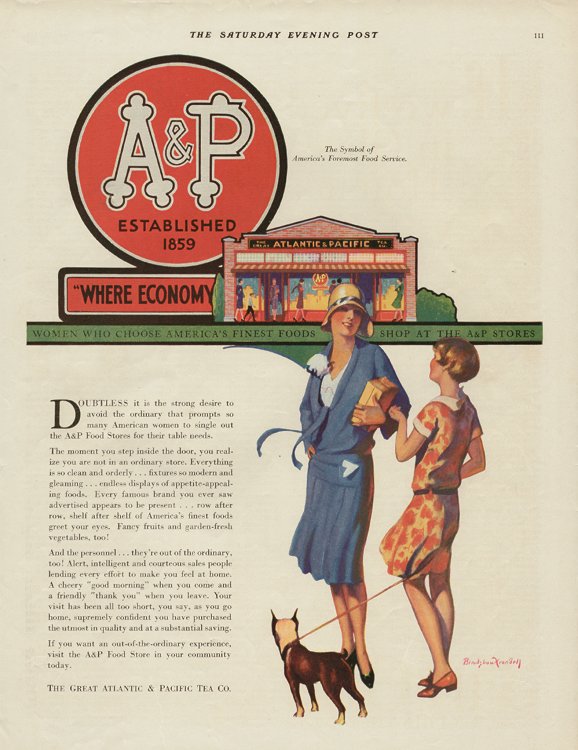

Although pervasive in its influence today, this consumer identity is a relatively recent invention. It only became a powerful force in U.S. politics in the years after World War II. To a large degree, it was created and propagated by the first generation of chain retailers-companies like A&P, Kroger, and Woolworth-which encountered such strong public opposition in the 1920s and 30s as to call into doubt their continued existence. The chains responded with a massive PR campaign that managed to transform American citizens into consumers-a sharply circumscribed identity that corporations have used to augment their power ever since.

Chain stores first began to multiply in large numbers in the years following World War I. During the 1920s, the number of chain stores climbed from about 30,000 to 150,000. By the end of the decade, they were capturing 22 percent of all retail sales nationally. Leading the pack was A&P, with some 15,000, mostly small, outlets that accounted for 11 percent of the country’s grocery sales and generated over $1 billion in annual revenue. A&P was the Wal-Mart of its day-although it was, in relative terms, significantly smaller, accounting for 2.5 percent of all retail sales, compared to Wal-Mart’s 10 percent share today.

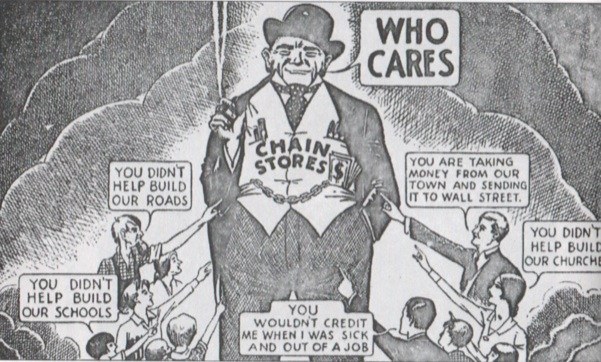

As the chains expanded, so too did opposition to their presence. It was a cause embraced by populists, progressives, unions concerned about wage pressures, farmers fearful chain store buying power, wholesalers, and of course local business owners. By the late 1920s, more than 400 local organizations had sprung up around the country to counter the chains. These “home defense leagues” and “better business associations” were varied in their approaches. Some, like the Community Builders in Danville, Virginia, never mentioned the chains, but instead promoted the idea, through billboards and radio programs, that money that stayed in town helped to build the community and its institutions. Other groups attacked the chains directly and exhorted people to boycott them. A campaign in Springfield, Missouri, urged, “Keep Ozark Dollars in the Ozarks,” and ran newspaper ads describing chain store managers as “mechanical operators” whose duty was to “get Springfield’s money and to send it to the Home Office.”

The anti-chain cause was the focus of at least forty newspapers and a dozen radio programs, including a broadcast by W.K. Henderson, the popular and foul-mouthed forerunner of today’s shockjocks, whose show, out of KWKH in Shreveport, Louisiana, was heard throughout the South and West. In 1930, the Reverend J.M. Gates, a prolific African-American preacher who sold tens of thousands of records of his sermons, including such hits as “Are You Bound for Heaven or Hell?” and “Kinky Hair is No Disgrace,” recorded one calling on people to “stay out of the chain stores.”

The anti-chain cause was the focus of at least forty newspapers and a dozen radio programs, including a broadcast by W.K. Henderson, the popular and foul-mouthed forerunner of today’s shockjocks, whose show, out of KWKH in Shreveport, Louisiana, was heard throughout the South and West. In 1930, the Reverend J.M. Gates, a prolific African-American preacher who sold tens of thousands of records of his sermons, including such hits as “Are You Bound for Heaven or Hell?” and “Kinky Hair is No Disgrace,” recorded one calling on people to “stay out of the chain stores.”

By 1930, “the chain store problem” had entered the national political debate in full force. The Nation ran a four-part series entitled, “Chains Versus Independents,” while The New Republic asked, “Chain Stores: Menace or Promise?” That year, the nation’s high school and college debate teams argued the proposition, “Resolved: that chain stores are detrimental to the best interests of the American public.” Several U.S. Senators and Congressmen ran on anti-chain platforms, while Progressive gubernatorial candidates in Wisconsin and Minnesota made the chains a central issue in their campaigns. An ex-governor of Texas reportedly “received a revelation from God to get back into politics and save his people from the chain-store dragon.”

Opponents argued that the chains threatened democracy by undermining local economic independence and community self-determination. As they drove out the local merchant — a “loyal and energetic type of citizen”– the chains replaced him with a manager, a “transient,” who was discouraged from independent thought and community involvement, and who served as “merely a representative of a non-resident group of stockholders who pay him according to his ability to line their pockets with silver.”

Many believe, wrote Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, author of Curse of Bigness and a strong advocate of vesting both economic and political power in local communities, that “the chain store, by furthering the concentration of wealth and of power and by promoting absentee ownership, is thwarting American ideals; that it is making impossible equality of opportunity; that it is converting independent tradesmen into clerks; and that it is sapping the resources, the vigor and the hope of the smaller cities and towns.” Chain stores drained money from communities, drove down wages, and squeezed producers. In a study of 45 chain and independent grocers in ten cities, two writers for The Nation found that prices at the chains were seven percent lower, but their wages were 20 percent less.

At a time when Americans had not yet defined their role in economic and political life as primarily that of a consumer, but still thought of themselves as independent producers, workers, citizens, and custodians of local communities, these arguments found widespread support. The chains’ overall market share stagnated, hovering at just over 20 percent through the 1930s and well into the 1940s.

Those opposed to chains sought not only to change people’s shopping habits, but to implement legislation that would retard their growth. In the mid 1920s, several state legislatures debated bills that would impose a special tax on chains. In 1929, Indiana became the first state to adopt such a tax. It was a graduated business license fee that increased according to the number of outlets a retailer operated, ranging from $3 a year for a single store up to $25 per store for chains with 20 or more outlets. The law was immediately challenged as a violation of the equal protection clause of the U.S. Constitution. Two years later, it was upheld by the Supreme Court in a 5-4 ruling that concluded that the distinction between chains and independents was reasonable enough to justify different tax rates.

Between 1931 and 1937, twenty-six states adopted chain store taxes. Dozens of cities did as well, led by Portland, Oregon, in 1931. Others, including Cleveland, Louisville, and Phoenix, soon followed. Some of these taxes, such as Indiana’s, were nominal enough to have little impact on the chains. Others were more severe. Texas assessed a $750 per store tax on chains with 50 or more outlets; Pennsylvania collected $500 on stores in chains exceeding 500 units. To put this in perspective, the grocery chain Kroger, which had 4,000 outlets in 1938, posted profits of about $1,000 per store, while Walgreen with 1,900 units earned about $4,000 per store. When figuring the tax, most states counted only the number of outlets within their borders, but Louisiana based its levy on the total number of stores the chain had nationally.

Although the U.S. Supreme Court upheld these taxes in several cases, including one challenging Louisiana’s law in 1937, it defined the scope of state authority very narrowly and somewhat arbitrarily. Variations on the standard chain store tax-the graduated license fee-were struck down by the Court, including laws in Kentucky and Iowa that taxed a retailer’s revenue, increasing the rate according to the volume of sales. The majority concluded-with Brandeis and two other Justices dissenting-that these laws treated national retailers differently from other retailers, violating their rights under the 14th Amendment, which was adopted after the Civil War to ensure all people equal treatment under the law.

The decision was built on rulings going back to the 1880s, when the Supreme Court had greatly expanded the power of corporations by extending to them the same protections granted to citizens under the Bill of Rights. It was a radical departure from the first century of U.S. history. Where once corporations had been subordinate to the public will, now they were given equal footing and potent legal rights. This expansive notion of corporate “rights” hindered states’ ability to regulate chains. It endures to this day and explains why mega-retailers have been allowed to initiate ballot referenda and engage in political campaigns: despite their superior financial resources, they are deemed to have the same rights as citizens to free speech and participation in the political process.

As cities and states continued to test the reach of their authority to regulate chain stores, Congress took up the issue, passing the Robinson-Patman Act, which barred large retailers from using their market power to coerce suppliers into giving them special deals not made available to independents.

Then, in 1938, Congress turned its attention to another proposal by Rep. Wright Patman, who sought to levy a national tax on chain stores. Co-sponsored by seventy-five Congressmen from 33 states, the bill would have dealt a death blow to most national chains. For those with more than 500 outlets, the base rate was $1,000 per unit. This was then multiplied by the number of states the chain spanned. Had the tax been in place in 1938, A&P would have owed $472 million in taxes on earnings of $9 million, while Woolworth’s would have been assessed $81 million on $29 million in profits. Patman’s bill phased in the tax over several years; the intent was to give the chains time to sell most of their stores to local owners.

By the time Congress considered Patman’s bill, however, the political terrain had begun to shift. The chains had mounted a massive public relations effort. It began in California in 1936, when the chains hired the Lord and Thomas Advertising Agency to gather signatures to force a referendum on the state’s newly enacted chain store tax and to wage a campaign against the measure.

Lord and Thomas advised the chains that they had three natural allies: their employees, suppliers, and customers. Under the ad firm’s counsel, the chains started calling employees by name rather than number, raised their salaries, and lessened their work load. They curried favor with farmers by absorbing a bumper crop of peaches. They tried to improve their community image by ordering store managers to join local chambers of commerce. Lord and Thomas dispatched an army of speakers, who extolled the chains’ virtues before any civic group or club that would listen.

Two months before the vote, the chains unleashed a barrage of radio and newspaper advertising. They sidestepped the issues of community self-determination, jobs, and local businesses, and instead cast the debate in the narrow framework of consumption. “Vote NO and keep prices low,” they urged. Early opinion polls had shown strong support for the tax, but on election day, it was trounced by a two-to-one margin.

The chains took their public relations campaign national, forming the American Retail Federation (which later became today’s National Retail Federation) to carry it out. They ran advertisements touting their consumer benefits and attacking the Patman tax in every daily newspaper in the country. They won over key constituencies, notably farmers and organized labor. Support from farmers came as the chains continued to buy up surplus crops, saving citrus growers in Florida, walnut growers in Oregon, and turkey farmers in New York. In 1938 and 1939, A&P, which had previously fought unionization, permitted its stores to be organized and signed a series of collective bargaining agreements. The company’s change of heart came “under the guidance of their public relations council.” In meetings with the president of the American Labor Federation, they cut a deal: unionization in exchange for labor’s opposition to Patman’s bill.

Most significantly, the chains continued to cultivate the consumer identity. The more people saw themselves as consumers-not producers, workers, or citizens-the less concerned they were about how the chains were impacting their livelihoods and their communities, and the more inclined they were to see the chains as satisfying an essential need for “quality, price, and better buying information.”

In 1939, Business Week reported that the chains had “reversed the trend against them.” Patman’s tax failed in 1940. The following year Utah voters rejected a chain store tax. No other chain store taxes were enacted after that point. Over the years, those on the books were either repealed or rendered irrelevant by inflation.

The post-war years saw the triumph of the consumer as the primary way in which Americans identified themselves and articulated their economic and political interests. The notion that the ownership structure of the economy ought to embody and support democratic values faded from view. Economic policy was no longer seen as an instrument for nurturing self-reliance and self-government, but for furthering efficiency and consumer welfare.

Brandeis’s stance in favor of decentralizing both economic and political power disappeared as a working policy position. Liberals instead resolved the problem of concentrated economic power by embracing a strong federal government that would regulate corporate America’s worst excesses and establish a social welfare system to absorb the fallout. Today, while liberals and conservatives may argue about the size and scope of the federal government, support for breaking up and dispersing economic power finds expression in neither of the major parties.

Unease about corporate power and a desire for greater community self-determination has, however, emerged once again as a potent issue at the local level. It’s evident in the rising interest in locally grown food and other products, and in the many cities that are setting their own economic policies, enacting such measures as living wage laws and ordinances that restrict the expansion of Wal-Mart and other corporate retailers. Many are also actively fostering the development of a locally rooted economy. Meanwhile, in some three dozen cities, local business owners have banded together in Independent Business Alliances that are calling on people as citizens to engage in a kind of economic disobedience by withdrawing support for the chains and shopping locally owned, as well as shaking up local politics by articulating a pro-business agenda that differs markedly from what’s put forth by most big business-dominated chambers of commerce.

It’s too early to tell, but these initiatives-which will be the subject of the remainder of this book-may well usher in a future America that is not dominated by a handful of global corporate giants, but rather embraces a decentralized economy more conducive to democracy.