Zika Has Landed

The BG-Sentinel 2 doesn’t look like a human, but to certain mosquitoes, it smells like one. The round trap stands about a foot and a half tall, with black netting on the side and a white top pitted with small holes. A cluster of clear tubes rests on top. The cylinders are stuffed with lactic acid, octenol and sodium hydroxide—a mixture that mimics the scent given off by humans.

As the smell wafts through the air, it draws in mosquitoes hungry for blood. When the bugs get too close, a fan sucks them down into a small black net, where they buzz around until someone from Sarasota County Mosquito Management comes to collect, kill and study them.

Chip Hancock, today’s executioner, bends over a trap that’s nestled in the V made by a pair of palm trees that stand at the edge of a ditch behind a house in Gulf Gate. Hancock pops the top off the trap and fishes out the net full of mosquitoes.

“The most I’ve ever seen in a trap like this is maybe two, three hundred,” Hancock says. As dribbles of sweat roll down his forehead, he peers inside to examine his catch. “It looks like we have maybe one or two,” he says. “We may have none. Which is what we hope to see.” The fewer he finds, the better, because today Hancock is hunting Aedes aegypti, one of two mosquito species known to carry and transmit the virus known as Zika.

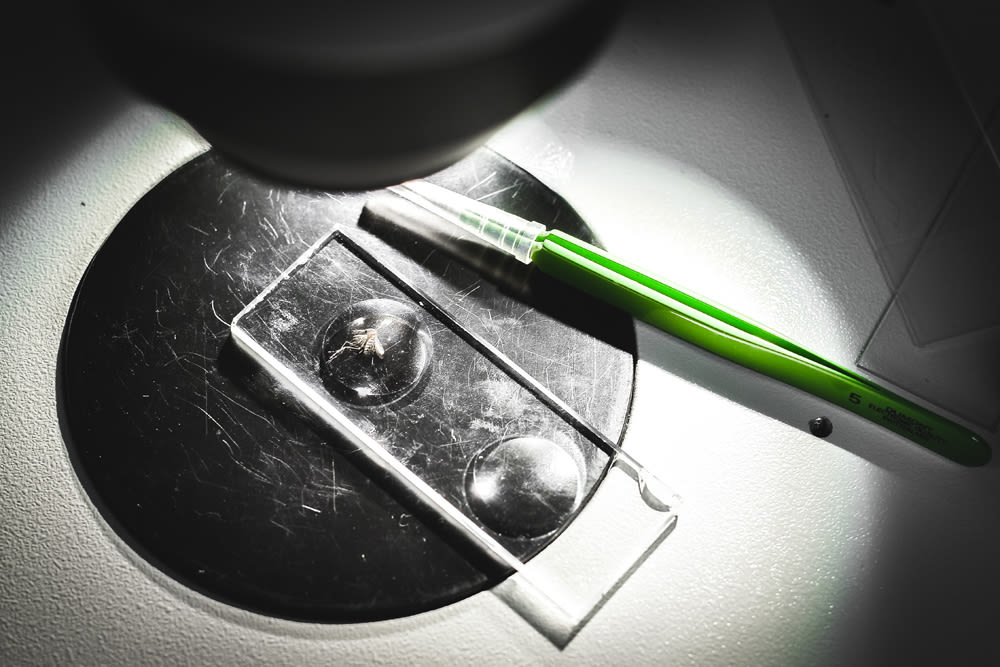

Biologists and students at the University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee are dissecting Aedes aegypti to identify the bacteria that live inside the mosquitoes

Almost 3,500 different mosquito species populate the planet, and 170 of them live in Florida, including Aedes aegypti, which terrorized the state long before Zika. We tend to think of mosquitoes as nuisances. In fact, they’re the deadliest animal on earth. Mosquitoes have killed more humans than all wars in history. In addition to Zika, mosquitoes spread malaria, yellow fever, dengue fever, chikungunya, encephalitis and West Nile virus, killing more than 1 million people each year. In 2015, malaria alone struck 214 million people around the world and killed 438,000.

Aedes aegypti, which originated in sub-Saharan Africa, likely arrived in the Americas in the 16th or 17th century. Gordon Patterson, a professor at the Florida Institute of Technology in Melbourne, theorizes that the mosquito reproduced in water barrels inside ships transporting slaves from West Africa to the Caribbean. The first documented yellow fever outbreak occurred in Barbados in 1647. When plantation owners in the Carolinas later imported slaves from Barbados, Aedes aegypti came with them, and it’s been feeding on Americans ever since.

Only the female targets humans—she uses the human protein found in blood to build yolk protein for her eggs—and she targets only humans. Unlike other mosquitoes that spread diseases like West Nile by biting birds and then biting humans, Aedes aegypti wants only human flesh.

She’s a fierce biter. She buzzes low and attacks ankles to avoid the slap of hands. After landing, she punctures your skin with her proboscis, then releases saliva that keeps your blood flowing until she’s sucked her fill. Unlike many mosquito species, which bite only when the sun is rising or setting, Aedes aegypti lurks in your yard in full daylight, waits for you to come out and attacks.

And she has been attacking Floridians—often fatally—for centuries. Yellow fever spread by Aedes aegypti ravaged Cedar Key, Apalachicola, Pensacola, Key West, Tampa, Plant City and Manatee County throughout the 1800s, a dreadful story recounted in detail in Patterson’s history of Florida mosquito control, The Mosquito Wars.

In 1877 in Fernandina, a coastal town near Jacksonville, yellow fever struck 1,146 out of 1,632 residents. Eleven years later, an even greater outbreak hit Jacksonville itself. The city was quarantined for nearly six months, with 5,000 confirmed cases and 427 deaths; 10,000 residents fled Duval County. The crisis ended only when temperatures dropped in the winter. (Mosquitoes fare best during long, warm, rainy summer days, and diseases replicate better in warmer temperatures.) The Jacksonville outbreak occurred during the height of the 1888 governor’s race and caught the attention of politicians in Tallahassee. The following spring, the Florida Legislature created the state’s first Board of Health.

It took years for researchers to isolate mosquitoes as the primary vector for yellow fever and other dreaded diseases like malaria, but once the connection was made, the state attacked mosquitoes with vigor. Workers dug runoff ditches to eliminate stagnant water and stocked water channels with minnows that devoured mosquito larvae. They added a thin sheen of oil to bodies of water to suffocate insects. They screened in dwellings and encouraged residents to add mosquito netting to their beds.

Killing mosquitoes wasn’t just a public health concern. It was an economic necessity. Settlers who moved to the Everglades in the early 20th century were terrorized by mosquitoes.

The bugs “came in swarms, they zinged and bored, they even brought droves of fireflies to light up the massacre,” wrote one Florida memoirist quoted by journalist Michael Grunwald in his book The Swamp. Mosquito control advocates argued that the Sunshine State would grow only once mosquitoes and the diseases they spread were eliminated.

Enter dichloro-diphenyl-trichloroethane. DDT. The chemical was discovered in 1874, but its insecticidal properties weren’t realized until World War II, when the military used it to ward off a typhus epidemic in Naples, Italy. Mosquito control agents in Florida began testing the chemical by spraying salt marshes in 1943, killing almost all the adult mosquitoes they came across. After World War II ended, the chemical was approved for civilian use, and just four years later, malaria had been eliminated in Florida. Along with air conditioning, mosquito control made Florida habitable.

But the triumph of DDT was short-lived. Mosquitoes and other insects quickly developed resistance to the compound. “If you use a chemical and it kills 98.8 percent of mosquitoes, that 1.2 percent will become resistant and repopulate,” Patterson says. By the late 1950s, DDT had fallen into disuse and been replaced by other chemicals like malathion. By 1973, more than 1 million gallons of insecticide were being sprayed across the state each year.

Sarasota County Mosquito Management biologist Chip Hancock checks a trap for Aedes aegypti

Having netted his Aedes aegypti in Gulf Gate, Hancock puts his captives in his white truck and heads back to the lab. Sarasota County Mosquito Management, founded in 1940 by public referendum, occupies a series of old one-story buildings in an industrial swath of south Sarasota. The campus includes a handful of offices and research facilities, as well as aquaculture tanks growing larvae-devouring Gambusia holbrooki fish, and chicken coops where birds are tested for viruses. If Sarasota’s steamy back yards and waterlogged ditches are the battlefield, this is the human command center, where mosquito experts research their opponent and plot how to counterattack.

“We take a scientific and careful approach,” says department director Matt Smith. His team uses a strategy dubbed “integrated pest management.” That means starting with the least toxic solution and moving toward more powerful methods only if necessary. The strategy was developed after researchers began questioning the indiscriminate application of pesticides. Rachel Carson’s 1962 book Silent Spring raised alarm about the damage pesticides cause to humans and wildlife, as well as their persistence in the natural environment. Today chemical sprays are just one weapon in the mosquito control arsenal.

“We don’t ever just spray chemicals into the air on any kind of set schedule,” Smith says. “It’s always done in response to data.” That data comes from traps like Hancock’s, set out in hundreds of spots around Sarasota County. Staffers collect the mosquitoes and bring them back to the lab, where the dead bugs are laid out and examined. Staffers peer through microscopes and identify the species bug by bug, tallying up their results with clickers. The county is home to 58 different mosquito species; only 20 or so represent a health threat.

After identifying species, staffers match the results to a map showing where the traps were set, telling the department what kinds of mosquitoes are popping up where. That information dictates how to respond. If it’s a localized problem, workers will strap on backpacks and do minimal sprays, dump larvae-hungry fish into ditches or abandoned pools or send out trucks for sprays. In swampy rural areas, where swarms of mosquitoes can take over large tracts, Vector Disease Control International, a private contractor, will drop mists of the insecticide Dibrom from planes over 64-acre plots. Timing matters. The department waits until a mosquito population crests and then sprays at night, when mosquitoes are active, to inflict maximum casualties.

In addition to Aedes aegypti, the closely related species Aedes albopictus can also transmit Zika. Smith says we have “modest numbers” of both types. We’re also home to Culex quinquefasciatus, commonly known as “quinks” or the “southern house mosquito.” It is a third species that has been linked to Zika. Labs have proven that the species is a “competent vector” but it hasn’t yet been found transmitting the virus in the wild.

Aedes aegypti is a “container breeder,” meaning it only reproduces in small vessels of water, like those slave ship barrels centuries ago. “They don’t breed in ditches, lakes, ponds, open water, swamps, none of that,” says Smith. Instead, they pop up inside bromeliads or in the base of flower pots, or even in receptacles as small as a bottle cap or a crease in a tarp. That’s one reason why the species sticks so close to humans. “You typically only find little containers like that around people,” Smith says, “because we leave crap lying around everywhere we go.”

If we could eliminate containers, goes the theory, we could eliminate the threat of Aedes mosquitoes and Zika. If we all walked around our yards once a week and dumped out every bit of standing water we found, the mosquitoes would have nowhere to reproduce. The species typically doesn’t travel farther than 200 meters from where it is born, so if you can eliminate it in your neighborhood, you don’t need to worry about it.

But that’s harder than it sounds. Even though Zika has generated headlines around the globe, not everyone is aware of the disease or informed about how to prevent it, and Smith’s department doesn’t have the manpower or the political mandate to march door to door, policing yards and overturning containers. Much of the battle against the disease involves educating people about how to fight Aedes aegypti on their own.

Zika has been transmitted in almost every country in South America, Central America and the Caribbean, as well as more distant nations, including Papua New Guinea and Cape Verde. More than 460,000 suspected cases of Zika had been identified as of mid-August, with 174,000 of them in Brazil alone. More than 2,200 cases have been reported in the United States—419 of them in Florida. Most of those cases involved people who had traveled overseas, but at least 14 people have been infected by local mosquitoes in several locations in South Florida.

Sarasota County has so far seen just one travel-related Zika case; Manatee County has reported two. Privacy rules prevent mosquito control workers from knowing patients’ exact addresses, but the Florida Department of Health passes along locations where Zika might have been transmitted. Protocol calls for trapping and research and sprays, if necessary, up to 400 meters from where the bite took place.

Aedes aegypti breeds rapidly in places with large concentrations of people whose homes don’t have screened-in windows and air-conditioning and who use barrels or cisterns to store water. As a result, like all mosquito-borne diseases, Zika disproportionately strikes the poor. Low-income Americans may not collect water in rain barrels, but their yards are likelier than those of more affluent Americans to be strewn with containers and they’re less likely to have air-conditioning. Patterson says most recent outbreaks of mosquito-borne diseases in Florida have struck poor people who lacked air-conditioning and information. Zika could follow the same pattern, he says: “Your air conditioner and your television set may be your best protections.”

Most mosquito experts say they’re concerned, not alarmed, about the potential of a Zika outbreak here. Smith claims it will be “super-easy” to bring the mosquito population down to zero in any local area where Zika is found. Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has however said that eradicating the mosquitoes in the Miami area where Zika was found has proven more difficult than they expected.

“Nobody should panic,” says Patterson. “That’s not the appropriate response.” Still, the disease and its unknown effects frighten many. There is no vaccine or treatment.

Scientists first discovered the virus in 1947 in a rhesus monkey living in Uganda’s Zika Forest and a year later found it in nearby mosquitoes. Human cases were identified as early as 1952, and the virus slowly spread around the rest of the African continent and eventually as far as Southwest Asia. In 2007, the first large Zika outbreak occurred on the island of Yap, one of the Federated States of Micronesia; the disease then hit several other Pacific islands. The first case of locally acquired Zika in the Americas was reported by Brazil on May 7, 2015.

Symptoms begin with a fever, rashes, joint pain and conjunctivitis. As of July, the death toll in this hemisphere stood at just 10, but the disease’s worst effects might be found among the next generation. Brazil has already reported more than 1,800 Zika-related cases of microcephaly, a condition in which a baby’s brain does not develop properly during pregnancy. Babies are born with deformed heads and brains, and can suffer seizures, severe developmental and intellectual disabilities and other problems.

Scientists also report a connection between Zika and Guillain-Barré Syndrome, which can lead to nerve cell damage, even paralysis. It kills one out of 20 who suffer from it. And some also fear the Zika virus might have latent effects that could emerge years after infection.

Further complicating efforts to study and battle the disease, many people don’t realize they’ve been infected with Zika. Four out of five of those infected will never experience even mild symptoms. The disease can also be spread from infected men to women during sex. But how likely is it for a baby to develop birth defects? How long does the Zika virus stay in semen? Many of the specifics of the disease remain unanswered, an ignorance exacerbated by political inaction.

This summer, Congress recessed for seven weeks after failing to approve any additional funding for Zika research at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. President Obama had requested $1.9 billion. In an interview with National Geographic, CDC director Frieden called Zika an “unprecedented threat to pregnant women” and lambasted Congress for doing nothing. “Mosquitoes don’t go on summer break. This is no way to fight an epidemic,” he said.

University of South Florida Sarasota-Manatee assistant professor of biology Aparna Telang examines an Aedes aegypti

In a small portable on the west end of the University of South Florida’s Sarasota campus, Aparna Telang is trying to find a new chink in the Aedes aegypti armor. Many mosquitoes collected by Sarasota County Mosquito Management end up here, where Telang and undergraduates dissect the insects. Telang is trying to figure out what kinds of bacteria live inside mosquitoes. Answering that question might provide a new weakness to exploit.

“We have decades of research on her and we still haven’t eradicated her,” Telang says with a baffled laugh. “It just goes to show the complexity of the problem. She is a formidable opponent.”

Telang and other mosquito researchers may be hunting for Aedes aegypti’s weak spot, but eradicating the species isn’t necessarily the goal. Destroying a species raises profound questions.

“How do we know that if we kill off Aedes aegypti, Mother Nature won’t come up with an even more sharp-toothed beast?” Patterson says. “I’m cautious about those who look for golden bullets.” Many ask what mosquitoes are good for, he concedes.

“Let’s ask, ‘Are humans good for anything?’” Patterson says. “We’ve come up with some really bad ideas. Mosquitoes, they’re pretty direct: They want a blood meal. They like water. And I do my best to tell people three words: Don’t get bit.”

In a cramped back room of Telang’s lab, the professor and her students are raising swarms of mosquitoes in a small screened box. They apply clear patches to their skin and then stick the plastic strips on nodes filled with pig blood. The heady mixture of pig blood and human scent drives the mosquitoes crazy.

As a visitor leans down to get a closer look, a swarm of tiny creatures moves close, dancing on the other side of the delicate screen. Forget swimming with sharks or alligators. As we move through our daily lives, we attract one of mankind’s most dangerous enemies with every compound our bodies give off. The female mosquitoes in Telang’s cage are well-fed and bulky, hungry and eager to pounce. Your scent and breath are making them crave your blood, Telang tells the visitor. She says with a laugh: “Oh, they’re fierce.”