They come from very different worlds, yet have remarkably similar tales to tell. One hails from the outskirts of Barnsley, in the small south Yorkshire mining village of Darfield. The other was brought up under the shadows of the magnificent slopes of Africa’s second-highest mountain, Mount Kenya.

Bonding over a “love of fine beer and a shared enthusiasm for science”, Steve Lancaster and Anthony Gachanja have come a long way since they met 28 years ago as PhD students, studying analytical chemistry at the University of Hull. Back then they were both the first in their families to attend university. Now, they are teaching scientists in Africa how to use analytical skills to solve global challenges.

Yorkshire roots

Leaving school at 16, Lancaster worked as a lab technician for five years, while studying part-time for a Higher National Certificate (HNC) in chemistry at Barnsley College of Technology. Despite “supportive and inspirational” science teachers, he always believed he would end up working down the pit as many of his elder classmates had.

“My secondary school chemistry teacher tried to persuade me that I should go, but at the time, I believed university was not for a lad brought up in a Yorkshire mining village,” says Lancaster.

It was only through peer pressure and encouragement from work colleagues that Lancaster ended up pursuing his university ambition at Sheffield Hallam University. He graduated with a chemistry degree, and was keen to continue studies at PhD level, specialising in analytical chemistry.

From the slopes to the east coast

Gachanja, meanwhile, had quite the journey from his hometown of Kirinyaga to studying in Hull. The sixth of seven children in his family, he spent his childhood in rural Kenya working on his parents’ farm and attending a small, basic local school. It was here he became captivated by chemistry.

“I just liked going to school, it was much better than doing the farm work,” chuckles Gachanja. “My parents were very keen on basic education and for me the sciences explained what was happening in the world.”

While his siblings went into agriculture and primary teaching, Gachanja left his rural home for the bright lights of the Kenyan capital city, Nairobi. He completed a BSc in chemistry at the University of Nairobi, before looking at potential international options for PhD study. Stumbling upon a noticeboard bulletin one day, he saw opportunities for sponsorship studying analytical chemistry at the University of Hull.

For Gachanja, boarding a plane was one thing, but moving country was a whole different feat. He vividly remembers arriving on Yorkshire’s east coast.

“Boarding a plane for the first time was exciting enough, but coming to the UK felt like a whole new chapter of my life,” says Gachanja. “I remember arriving in October, coming from a tropical country, to biting temperatures – I was constantly lost.”

Recounting tales of perplexing accents, getting hopelessly lost in his own halls of residence, and countless lectures trying to interpret local linguistics he also recalls being “dazzled” by the sheer amount of equipment available in the university’s laboratories.

“I had not seen many of the instruments before, let alone used them. My impression of UK science was that the science teaching was very high and the lab equipment readily available – I wasn’t wrong,” he says.

“The difference between African and European laboratories is stark and Africa is a long way behind in terms of gaining exposure to different instrumentation.”

Meeting of like minds

It was in the university laboratory that they first met. Lancaster was studying chemiluminesence – developing organic reactions that emit their own light - while Gachanja was looking at the chemistry of various cooking mediums, including wood and dung. Their enthusiasm to know more about science and go beyond the experiment results was what initially sparked the friendship.

Following their respective courses both continued in analytical chemistry, Lancaster taking a research and development role at BP , while Gachanja went on to postdoctoral studies at the University of Plymouth, before making the difficult decision to move back to Nairobi after over a decade in the UK.

Returning home

Torn between an extremely attractive career in a developed country or returning home to laboratories lacking basic equipment, Gachanja was forced to decide who needed him most as an analytical chemist: Africa or the developed world?

“One part of me really wanted to remain in the UK, but my gut was telling me I should go back to Africa to see what I could do for instrumentation and the use of analytical techniques in Africa,” he says.

Realising his impact on science would be greater back in Kenya, he returned. His immediate actions were to spend a number of months visiting different industries across the country to discuss their analytical problems and needs. Here he saw first-hand the challenges facing chemists working in analytical laboratories. Gachanja strongly believes that improper access to analytical techniques has had a detrimental impact on many of the country’s sectors, including the economy, trade and the environment.

The figures on African science at first glance read starkly. World Economic Forum research shows Africa produces only 1.1% of global scientific knowledge , with just 79 scientists per million Africans, compared with 4,500 per million people in the US. Yet there is hope. Research output more than doubled across sub-Saharan Africa between 2003 and 2012, with much of this growth in the life sciences sector. Some argue though, that science and technology has never been seen as central to decision-making processes and has resulted in a “brain drain” of talented African scientists leaving the continent.

“You get to Africa, you have the knowledge, you have the energy, but you don’t have any facilities. How are you supposed to learn practical skills and do basic research?” says Gachanja.

It was this very predicament that led Gachanja to call for help in 2004. Finding resources extremely scarce in his new role as a professor of analytical chemistry at Nairobi’s Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology (JKUAT), he knew there was one friend he could count on.

“It was getting frustrating and I knew I needed help, so I called Steve to see if there was any way we could get equipment over to Nairobi,” he recalls.

Lancaster immediately responded and started to put feelers out to colleagues and industry contacts. “I managed to identify a company that was willing to donate a Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS) machine fairly quickly, it was just then a matter of raising funds to transport it over and send an engineer to commission it,” says Lancaster.

This sparked months of fundraising activities and a collaboration lasting more than ten years. As well as helping source, ship and install a GC-MS instrument in the laboratory one year later – a first in a Kenyan public university – the friends realised that there was more to be done.

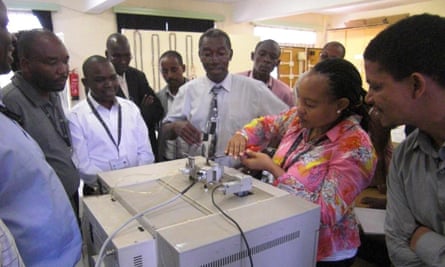

“We decided equipment was one thing, but training scientists in Africa in the local laboratories on instrumentations, another,” says Gachanja. “So Steve and I chose to team up and train scientists on GC-MS – a fantastic technique for analysis on a wide range of substances.”

A combination of Gas Chromatography, which separates complex, volatile mixtures into their constituent parts and Mass Spectrometry, which allows the scientist to identify the substances that are present, Gachanja describes GC-MS as one of the most widely used and powerful analytical techniques in use today.

Emphasising the importance of analytical chemistry beyond the laboratory, he highlights government agencies as significant employers of analytical chemists, working in areas as diverse as environmental monitoring, food safety and forensic science.

Training future scientists

In 2005, Lancaster found himself in unfamiliar surroundings, much like Gachanja had years before him. It was his first time in Africa. “Africa was a lump of land on a map that I learnt about in geography when I was at school, and that was as far as it went,” says Lancaster. “The thing that immediately hit me in the face was the poverty.”

He was visiting Nairobi, to hold the first ever training session with Gachanja, for African students, academics and industry. “It was very informal back then and we had a small number of around 15 people from across Africa attend,” says Lancaster.

In the sessions, participants would learn how to use the instruments, interpret the data, and understand how the data could be used when checking the purity of pharmaceuticals or identifying counterfeit drugs.

“They had all seen the machines in textbooks and were all very well versed in the theory but there was a certain reluctance to use the instruments for fear of damage,” says Lancaster. “After the first few days, we got them over their initial fears, and it was incredible to see the transformation getting results from their samples.”

What started as low-key soon morphed into an annual training session, the introduction of degree programmes with an analytical chemistry focus in some Kenyan universities, and funding from international organisations.

Following years of sponsored bike rides, walks, driving across Europe in a car that cost just £200, as well as a third instructor joining the team (Mathias Schäfer, from the University of Cologne), the sessions were to be funded by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) and the Royal Society of Chemistry’s Pan African Chemistry Network (PACN) – a network set up to provide support for researchers across sub-Saharan Africa.

“Over the years we’ve raised more than £60,000 to send instruments over, keep them running and provide training,” says Lancaster, who still fundraises. “The PACN has been great in providing the resources and organisational aspects of running the courses, such as advertising to students.”

Lancaster, who went onto work as an analytical chemistry programmes manager at the Royal Society of Chemistry, before joining technology company Domino, reiterates the importance of analytical skills in African science.

“Analytical data is used in every walk of life,” he says. “When you buy food from the supermarket, you want to know the food is good quality and not contaminated with pesticides or pollutants. In order to do this, you need to do analysis and very often this is GC Mass Spec. Same with drugs, water quality and the blood or urine samples your doctor sends off for analysis – without this skill Africa can never develop to be an advanced 21st-century economy.”

The programme has trained more than 200 scientists to date and contributed to a wealth of articles in scientific journals. However, what Gachanja says is most promising is the shift in mindsets, as scientists are more confident using the machines, which in turn, has led to a higher demand for research and therefore more research actually being carried out.

“Barriers have been removed and the improvement in research output has been very promising,” says Gachanja, who believes the training can be replicated across developing countries. “I am very happy to see the potential for future generations of African trainers, leaving a legacy, for many years to come. If I accomplish one thing before I retire, it is to have improved the level of awareness that analytical chemistry has in Africa.”

Just last month, a five-year partnership was agreed between the Royal Society of Chemistry and GlaxosmithKline (GSK) to fund the programme, and expand it to four countries including Kenya, Nigeria, Ethiopia and Ghana, training 400 scientists.

“Science skills should be shared for the benefit of mankind,” says Gachanja. “Right now for me, analytical chemistry is a way of life. It is not like I go to work and do chemistry and come home. I see chemistry everywhere I go.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion