Along the road sped the white Transit van, carrying its precious cargo. In its back were stacked rows of black Thermo boxes containing 750 freshly made children’s lunches. Chefs had been making them since around 4.30am that morning, working in a large kitchen on a small industrial estate a few minutes from Liverpool airport. Now it was just gone 9.30am and we were driving them over the bridge to north Wales and the playcentres of Flintshire.

For some children at the other end, this white van contained their first meal of the day. Simon Bazley, a play worker at the biggest centre of the lot, Quayplay, said, “If they don’t get school meals, some of them won’t eat. They come here hungry and angry.”

None of this is unusual. For around 13 weeks of the year when school is out, free meals are over – and family poverty across Britain is pitilessly exposed.

Here, in the sixth-richest country in the world, up to 3 million children spend their school holidays at risk of not getting enough food, according to an investigation by a cross-party group of MPs and peers. Their report into holiday hunger, published last summer, contains testimony of a child vomiting “because their diet consisted entirely of crisps”, as well as a group of kids dropping out of a football tournament “as they had not eaten a meal” for days beforehand. “Their bodies simply gave up on them.”

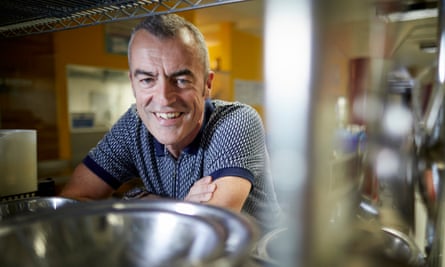

Such is the evil the chefs at Can Cook in Garston, Liverpool, are fighting to keep at bay this summer holiday, by making well over 4,000 free hot lunches a week for nurseries around Liverpool and playcentres in Flintshire. Can Cook makes a lot of free meals: 37,000 around Merseyside alone. This latest consignment was being chauffeured by the social enterprise’s boss, Robbie Davison.

Senior Conservatives would have you believe they love people like Davison. The former welfare secretary Iain Duncan Smith said, “I welcome food banks. I welcome decent people in society trying to help others who … have fallen into difficulty.” Last autumn, Jacob Rees-Mogg declared food banks proof of “what a good, compassionate country we are… To have charitable support given by people voluntarily to support their fellow citizens I think is rather uplifting”.

Davison is propelled by a kinetic anger. “An absolute, diehard socialist”, he despises that language and those politics. He doesn’t want to be dishing out charity. Most of all, he hates the food aid system. Chief among his targets are two of the biggest food charities: the Trussell Trust, which is synonymous with food banks; and the nationwide distributor of surplus food, FareShare. He’s trying to build an alternative to food charity. It’s caught the eye of the shadow chancellor, John McDonnell, who has popped by to praise Can Cook’s work and whose aides want Davison at Labour conference next month.

Davison condemns food banks for serving “poor food to poor people”. In the back of Davison’s Transit, by contrast, are what he calls “good, healthy meals”, the kind Can Cook taught Liverpudlians to cook when it launched just over a decade ago. Davison began as a kind of Jamie Oliver, trying to ignite a cooking revolution in post-industrial Britain years before the TV chef carted his Le Creuset to Rotherham. Except, unlike Oliver, he grew up with the very people he was trying to win over.

A few minutes into our drive, Davison pointed over to his childhood home, the vast township of the Speke estate. “Like an island on the outskirts of Liverpool,” he said. “All sorts of things go on there that no one else ever knows about.” He was his family’s secret, raised by grandparents as their own son while his 14-year-old mum pretended to be his sister.

Then came years on the dole and as a carer, giving Davison a solid grounding in the reality of being broke. When he started cooking lessons, “nobody in their 20s or 30s had seen fresh food”. People would complain that his team was using obscure ingredients. What were these “spices” they kept going on about?

To prove them wrong, he ran over to the local grocer and asked for the spice rack. “The supervisor came over and took me to the Oxo cubes. He thought Oxos were spices.

“That’s the kind of food intelligence you’re dealing with. People are so disconnected from what they eat. If people don’t know what a spring onion is, don’t talk to them about five a day.”

As they spotted the white van pull up at Quayplay in Flintshire, children broke off from sliding down the hill on cardboard sleds and began speculating about what was for lunch. On being told it was chicken and noodles (wrongly), one said, hesitantly: “I have Super Noodles, and they’re chicken-flavoured. Is it like that?”

Inside the dining hall were low tables and toy chairs and boys tentatively forking through their Chinese chicken and rice. “You have to mix the offer or you’ve got no chance,” said Davison. “We hand-make fish fingers sometimes and some parents will say, ‘Don’t give them that healthy crap, give them Bird’s Eye.’ If I turned up with spinach and quinoa they’d tell me to stop feeding their kids shite.”

As if on cue, a blond boy of around seven held out his fork to me. “What’s this?” It was a slice of courgette – something he said he’d never seen before. Unlike my school meals, which looked like they had suffered death by blender, the meat and veg rested in their sweet sauce in thickly cut chunks. His mate held out his fork. “What’s this?” It was half a button mushroom.

Jan, a supervisor at the playcentre, came over. She had something else to get off her chest. “Children should not be victims of austerity, should they? Because they don’t have a vote, they’re relying on us. So the fact there’s a shortage of food, it’s up to us adults to sort it out.”

Davison looked out of this hall at the top of the hill and guessed there would be about 10,000 households in the area – “and probably 4,500 of them are moving in and out of food poverty”.

To my eyes, food poverty looks like any other form of poverty: it’s about not having money. But Davison argues otherwise. “You can’t do anything if you’ve got no food.” I put it to him that you can’t do anything if the house is freezing and sticking on an electric-bar heater will blow your budget. He simply replies, “Put a coat on,” and adds: “I know it sounds hard, but hunger is different.”

The million households that last winter faced a choice between heating and eating might disagree, but Davison rolled on. “Everybody organises their lives around food. ‘See you at lunch!’ ‘When’s teatime?’ We stop functioning if we’re hungry. You give people the means to eat and they will get themselves out of any hole.”

It’s clear that for him this isn’t about food so much as dignity. Food in Britain remains a proxy for class. And here is the chief sin of the big food charities, in Davison’s eyes: they feed poor people what they can, not what they need or want. In doing so, they deny poor people the self-respect of eating properly – and a route out of poverty.

To see what he means, look at the Trussell Trust’s own analysis of its emergency food parcels, published in April. Food scientists at University College London describe the three-day parcels as “nutritionally adequate”, albeit with far too much sugar. Getting those stuffed carrier bags may be a lifeline, especially for the 60% of food bank visitors who report not having eaten for days. But the scientists note that, while the likes of Asda and Cadbury focus-group and taste-test to death, the Trussell Trust doesn’t give its consumers much of a say over what they get. “Food parcels could be developed to better meet the needs of clients, while being pragmatic and nutritious,” says the report.

While the Trussell Trust asks food-bank managers for input and to offer feedback forms, it argues, “We’re an anti-poverty charity, not food experts, so we dedicate our resources to improving the support we give and campaigning so we don’t need to give that support in the future.” It also works with “independent nutritionists, who advise on the contents of our parcel and what we can do to improve it”.

The Trussell Trust was never meant to be based in Britain. Its founders, Carol and Paddy Henderson, began by feeding children sleeping rough in Bulgaria. Only when a desperate neighbour in their home town, Salisbury, asked for help did the Hendersons start distributing food out of their garden shed. Similarly, FareShare began life giving homeless people surplus food from Sainsbury’s. Two decades and 420 food banks later, both charities are now huge.

As the government ignores requests from UN agencies even to monitor food insecurity, town halls and Whitehall now treat food charities as part of the greater welfare state. Says food policy adviser Lindsay Graham: “Food banks are here to stay. They are now part of the system, whether we like it or not.” What was ad hoc is now industrial.

As food aid has become bigger, it’s attracted more and more controversy. In 2016, FareShare was reported by the website Vice to be using workfare labour in its distribution centres. And just this year, both charities signed a £20m partnership with Asda, the supermarket giant that was itself reported in 2015 to employ 120,000 workers who had to have their pay topped up by government benefits.

FareShare tells me the deal “will enable us to expand warehouse capacity and to buy new forklifts, vans and chillers in order to handle, store and redistribute much more good-quality surplus food. This will in turn enable us to have the capacity to help feed even more people”, while Trussell says the cash “will provide support directly to food banks and support us to develop our research and campaigning work”.

But umbrella group the Independent Food Aid Network formally protested against the deal “when colleagues across the sector are seeking ways to move the UK away from its reliance on charitable food aid and address the wider problems of food insecurity”.

Davison prides himself on running not a charity, but a social enterprise run on a business-like basis. His staff are not volunteers but on the real living wage.

Back at Can Cook’s kitchens in Liverpool, he showed me a recipe video produced by a food bank. A dutifully jovial cook was demonstrating how to make a pasta bake, using ingredients from a food parcel. It started simply enough: half a bag of pasta, tuna, a can of tomatoes. Then things took a turn for the perverse: he dumped in a tin of peas and another can of spaghetti hoops, telling us to “really take a little bit of time to make sure everything’s nice and combined”.

Davison was almost spitting. “A chef instructing other people to eat in the crappest way possible! No one in the world eats like that. Not if they have a choice.”

Against that, Davison is negotiating with councils to establish good food areas, in which food banks will form a part – but only a small one. Primarily, the plans rest on taking surplus food from farmers and producers and cooking it into meals (“as good as Tesco’s Finest or M&S”) and selling them to schools – setting aside money from each contract to provide meals for others. The dishes would also be available from food banks and as a meals-on-wheels service. But Can Cook’s other innovation would be to sell them for £2 a pop in convenience stores, so that those who can’t face or aren’t referred to food banks can still get high-quality, low-price meals.

On its Facebook page, Can Cook has a video from last year of John McDonnell being shown the plan by Davison. You can see how large and ambitious the scheme is, but the shadow chancellor cottons on to its importance. He responds: “We can’t allow our society to become dependent on food banks … We’ve got to have a new model that’s sustainable and that gives people decent food.” Davison thinks the first good food area should be up and running by Christmas.

A lot could go wrong. Councillors might lose their nerve, while Can Cook struggles with social-enterprise syndrome: having to jump through a series of hoops to raise funds. But if Davison pulls it off, he’ll have found a way to use the social institutions of the everyday economy – schools, care homes, corner shops – to sustain a smaller, fresher and more local food system. In a Britain that has got used to firms like Carillion serving up school meals, that would be a radical departure.

Before leaving, I spoke to Tony Evans, the head chef at Can Cook. “My dream was to be a Michelin-starred cook. But that’s not real food,” he said, his accent betraying his south London upbringing. “This is probably the hardest job I’ve ever had.” Then he recalled “a young lad” at one of the Liverpool schools he caters for. When they started serving meals, “he was starving. He’d be coming up for seconds and thirds. He’d be acting up, acting out.” Now, with decent school lunches and being given a few dinners and slow-cooker meals to take home, “you can just see the difference. He’s not running around like a lunatic any more.”

Up since well before dawn, Evans had been cooking for 10 hours already and was about to be interviewed by a food magazine that had shortlisted him for community chef of the year. His day had another couple of hours in it yet, but for now he was enjoying thinking of this boy. “That’s what gets me out of bed. Every time.”