SDPD’s drive to get back to community policing

Department was once in the vanguard of interacting with citizens it serves; but budget cuts, service demands caused it to stray

Soon after San Diego police Officer Richard Valenzuela graduated from the academy in 2008, he stumbled on what he hoped would be his first community project.

It was an old house in City Heights. The neighbors hated it. The windows were boarded up and the inside was covered in graffiti. Shady characters were spotted moving in and out of it at night.

To a fresh-faced officer, dealing with that neighborhood problem was what being a cop was all about, especially at the San Diego Police Department, which since the 1980s had championed working with the community to solve problems — the foundation of community-oriented policing.

Senior officers showed Valenzuela the ropes, teaching him how to contact property managers, and how to get the go-ahead to police on private property. He got to work.

“Once I hit the streets I was so excited, and that’s the first thing I did. I found that one house,” Valenzuela said. “I talked to people around the neighborhood. They said, ‘Yeah, that house has been so problematic…’ This was my opportunity. It was excellent.”

But then he got into his patrol car and got a radio call. Then another. And another. From his shift’s start to its end, he rushed from call to call.

“Not to make excuses,” Valenzuela said, “but we felt that we were limited in the time we had to work on those things, or they would take longer. Handling those calls. That’s what was driving us.”

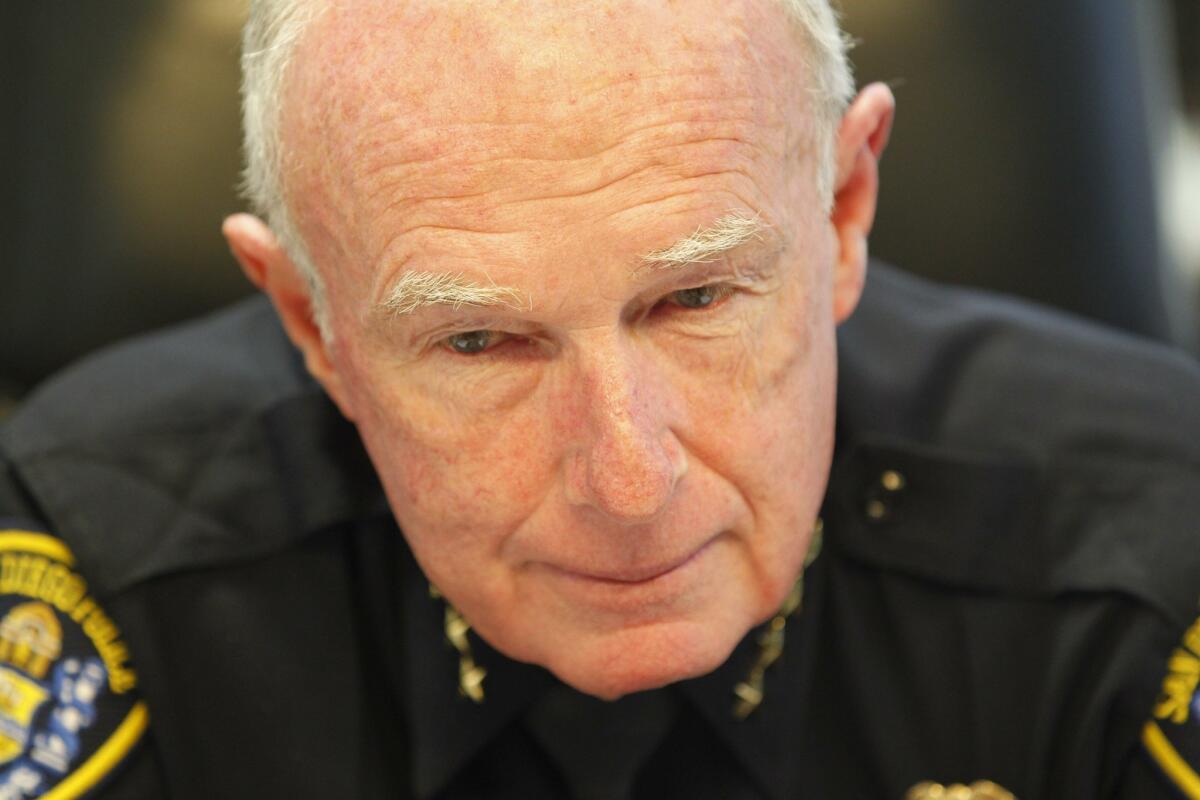

Fast forward to February 2014. Then-San Diego Police Chief Bill Lansdowne asked the U.S. Department of Justice to conduct an audit of his department, which was mired in the scandal of officer misconduct that included drunken driving, drug dealing and sexual assaults.

After a yearlong investigation, the feds doled out 40 recommendations. Most were ways the department could better deter and prevent misconduct, but the report also included suggestions intended to help restore public trust. Eight of them focused on how the department could better forge community relationships. (See audit recommendations, results, below.)

So how did the department go from leading national conferences on community-oriented policing to being cautioned by the Department of Justice that it needed to do better in that area? And was San Diego alone, or were departments across the county, throughout the nation — in other countries — struggling to make community policing happen, too?

Brief history lesson

At its core, community policing is about partnering with neighborhoods to identify and solve problems that might lead to crime. It’s more about prevention than response. The philosophy emerged in the late 1970s, and by the early 1990s, it was being embraced by police departments around the world.

Starting in the 1960s, crime steadily started to rise, peaking nationwide around 1991. Violent crime hit its height in San Diego County in 1992. Understandably, police were very crime-focused, said Jason Stamps, the associate director of the Center for Public Safety and Justice.

“They were focused on bringing down crime rates, solving crimes, catching bad guys and putting them in jail,” he said. “Which is good, but that singular focus started to create distance between (officers) and the community.”

That enforcement mentality, compounded by instances of police abuse, fueled tensions, especially in communities of color.

Crime began plummeting in the early 1990s, but a number of agencies discovered that community relationships had been strained in the process.

Meanwhile, sociologists and other academics were finding correlations between small neighborhood problems and larger crime issues.

“Community-oriented policing was that first effort at bringing law enforcement and the community back together,” Stamps said.

It was also supported by minority communities as a way to curb police violence.

The Department of Justice’s Community Oriented Policing Services office was created in 1994 and a nationwide network of community policing institutes was set up to study the philosophy and help departments do it well. But a handful of departments were already doing it well, including the San Diego Police Department.

In the late 1980s, the department had begun encouraging officers to partner with community members to identify neighborhood problems that might cause crime later. The strategy was called problem-oriented policing, and it’s a pillar of community policing.

It was a time-consuming, resource-heavy process. Officers and residents would get together, research a problem and explore solutions. They tackled crime hotspots, but the process also cultivated trust and transparency.

San Diego was internationally recognized for how it embraced the philosophy, with articles and awards. It even hosted the first national conference on the topic.

As the crime rate reached unprecedented lows in the late 1990s, both locally and nationwide, community policing was hailed as a success.

Financial constraints

Lansdowne took the helm in 2003. Shortly afterward, a municipal pension crisis thrust San Diego into financial turmoil.

Police contract negotiations increased pension fund contributions and salaries were frozen as the city tried to tackle a $2 billion deficit. The result? San Diego police officers left in droves to other departments or other industries where the benefits were sweeter.

“The city was in a very tenuous financial position, and it caused us to make changes,” Lansdowne said. “... It was detrimental to the way we were policing, but there weren’t a lot of alternatives, as we looked at the possibility of bankruptcy.”

By 2006, the department’s staffing levels were in crisis mode, according to then-San Diego Mayor Jerry Sanders. And that was before 2009, which saw an exodus of 264 officers. The department went from 2,102 sworn officers in 2004 to 1,821 in 2012.

Lansdowne said the department was forced to do business differently — and community policing suffered.

“Very clearly, at least to me, was (the need) to keep our beats staffed so we could get to emergency calls within a seven-minute timeline,” he said. “To do that, we had to move people to patrol, and we couldn’t support the specialized individuals that were dedicated to ... community policing.”

Neighborhood storefronts, where citizens could conveniently interact with officers, were mostly shuttered. Bicycle and foot patrols were cut or eliminated. Problem-oriented policing continued, but projects were fewer and farther between, and staff and officers in positions dedicated to community policing were laid off or returned to patrol.

Lansdowne said he heard from officers and community members about the changes. No one was happy.

“I can’t tell you how many discussions I had in meetings with officers who said they’re feeling like they’re rushing through calls, and in their heart they want to spend more time but they couldn’t do it,” he said. “... It was a huge frustration.”

The department also scaled back on police service officers, who are not uniformed officers, and community resource officers, the officers who had been attending community meetings and neighborhood events. For many residents, they were their connection to the department and its face. In 2010, the department went down to 11 community resource officers, a task that been shared by dozens of officers before. The number of police service officers went from 57 to eight.

“The community was getting the impression that we weren’t as committed as we were before because they didn’t see as many officers,” Lansdowne said.

Meanwhile, more was being asked of the front-line officers.

“Officers were demoralized, stressed out, and you saw that manifest itself in a variety of ways,” said San Diego police Lt. Scott Wahl, the department’s chief spokesman. “There was an exodus from the profession, there was officer misconduct, I don’t know if you can factually prove that was the cause, but I think it would be very naive to say that the stresses of the job compounded by the economic downturn and that level of responsibility — that that didn’t contribute.”

A national decline

Robert Chapman, deputy director of the federal community policing office, said similar stories unfolded nationwide after the economic downturn of 2007-08.

The office commissioned a report to assess the impact of the recession on community oriented policing. It surveyed the Major Cities Chiefs Association, a group of chiefs and sheriffs from the largest cities in the U.S., Canada and the United Kingdom, and of the 42 agencies that responded, more than half said the recession affected their community policing efforts.

“We were hearing it was creating challenges and constraints for police agencies across the country,” Chapman said.

There were other factors, as well. A new policing strategy called intelligence-led policing emerged and was embraced by some local agencies, including the San Diego Police Department. The practice involved using data to analyze and predict where crime might occur, allowing departments to more efficiently deploy resources that were suddenly limited.

“We used data to analyze where crime was happening and then we put people there to prevent it,” Lansdowne said. “But by doing that, you took (officers) out of other neighborhoods.”

Many departments said staffing shortages contributed the most to cuts in community policing initiatives.

Chula Vista police Capt. Lon Turner said the department went from about 250 officers to 190 in two years. The department eliminated programs to keep patrolling at a bare minimum.

“Community-oriented policing takes a lot of resources to do well, and for many years we were downsizing our organization,” Turner said. “The department did what it could to still provide specialized policing to communities, but follow-up for investigations, responsiveness — it all suffered.”

At one point, the department cut its number of school resource officers from 20 to 10.

“We had less interactions with kids and that’s a big deal,” Turner said. “It’s important that they see officers in a positive light, that they have positive interactions.”

Other departments, especially ones that didn’t lose officers, were able to maintain community programs, but it wasn’t easy.

Oceanside police Lt. Leonard Cosby said the department considered scaling back its neighborhood policing team to beef up patrol, but ultimately decided against it.

“I can tell you, officers (in patrol) got upset, because they saw how those neighborhood officers could help them,” he said.

The decision wasn’t just about where those officers would be most effective. Leaders also didn’t want to send the wrong message to the public.

“Are you telling them that you’re abandoning them? That what you were doing in the first place wasn’t worthwhile?” he said. “We committed ourselves to the philosophy, and that meant committing our officers, too.”

The federal community policing office was affected as well. In 1994, when it was founded, the federal agency had a budget of more than $1 billion. This year, it was just more than $200 million.

A number of local departments said grants that allowed them to take on special community policing projects dried up in the wake of the recession.

“It was worse than going to Vegas and dropping your money in a slot machine,” Cosby said. “One year you’d get a certain amount of money and the next it was half that. The projections were that it was going to keep shrinking.”

The philosophy also had its critics. Some charged community policing was “merely a triumph of public relations,” as one review on the practice said. While community policing consistently improved a community’s perception of police work, there isn’t solid evidence that it reduces crime.

In a 2014 review of 25 reports containing 65 independent tests of community-oriented policing, researchers found the practice had a positive effect on citizen satisfaction and the perceived legitimacy of police, but a marginal, if any, effect on crime, according to the study published in the December 2014 Journal of Experimental Criminology.

Others argued community-oriented policing was an expensive and time-consuming strategy that, if not employed correctly, wasted resources and was the job of a social worker, not a police officer.

Despite such challenges and criticisms, local departments and most surveyed by the community policing office said they remain committed to community policing as a strategy.

Back to basics

The San Diego Police Department recently added nine new community resource officers. It also instituted a new department-wide training program and one for academy graduates with a special focus on community engagement.

But had the department’s culture changed?

Around 2008, Bishop Cornelius Bowser, who runs the Charity Apostolic Church in Santee, partnered with the San Diego department to combat gang violence.

Then, several years later, he helped shape the Community Assistance Support Team. Tackling gang activity was still a priority, but Bowser also wanted to create relationships between members of the community and the police to promote problem-solving of all kinds.

The group started doing something called the walk-and-knock. Community members and police leaders would walk through the neighborhood, meeting and greeting residents along the way.

“We want them to see the police in a different light, engaging them in conversation, just talking with them,” Bowser said.

At first, neighbors didn’t know what to think. Bowser said a couple of residents saw police going door-to-door and assumed someone had died, or a child had been kidnapped. That’s because for years, Bowser said, it seemed like police only showed up when something was wrong.

“The officers and the people we work with have the same goal: to prevent crime and build bridges,” he said. “But when the rank-and-file officers out on the street are always in the mode of 911 and reacting to crime, it makes it difficult to build that relationship.”

The bishop said while he and other community leaders enjoy strong relationships with department leaders, the public at large, especially black and Latino residents, has a lot of hostility toward law enforcement.

“From one perspective, we have the police department working with us and walking in our communities, but then there are these officers in the field,” Bowser said. “They may feel like they’re doing their job, but the community feels harassed. Picked on.”

San Diego police Lt. Natalie Stone remembers watching her relationships with residents get icy, as community projects took a back seat.

“I remember, the people in the community used to wave at you, they supported you,” she said. “The nationwide tide that’s turned on law enforcement, that’s part of our lack of engaging the community.”

Across the nation, tensions between communities and law enforcement have imploded, and protests and rioting erupted. Most were set off by a specific incident — when Michael Brown, a black teen, was fatally shot by a white police officer in Ferguson, Mo., or Eric Garner was choked to death in New York — but the unrest that followed was fueled by years of toxic relationships.

“People see us (just) as some cop driving by going somewhere fast,” Stone said. “...You see the repercussions of that in the national news every day.”

Officials say that some officers, especially younger ones, don’t remember what policing was like before the incessant demands coming from their radios. They say they didn’t get taught how to interact with community members or the importance of seeking positive interactions. A different culture of officer was being cultivated, one that didn’t have time, or wasn’t making time, for community policing.

“Who teaches you about the culture of an organization? Your elders, right? But they’re gone,” Wahl said. “Suddenly you’ve got this new, young organization and all they’re seeing is you get in your car, you hit that you’re available and it’s radio call after radio call until the end of your day. ...”

“Suddenly, we had a generation of officers that was at risk of not knowing how to community police, or how to be proactive in between answering those radio calls.”

When Shelley Zimmerman became police chief in 2014, restoring community policing initiatives was immediately made a top priority, because, department leaders said, the federal report just confirmed what many already knew: San Diego police officers weren’t the problem solvers they once were, and it was time for an intervention.

Like many departments, San Diego police started coming up with ways officers could incorporate community interactions into their already busy days.

Officers embraced email, answering concerns from residents when they had down time or on their days off, Wahl said. They launched Twitter accounts and signed up for Nextdoor.com, a neighbor-to-neighbor site the department has come to rely on for community engagement.

But department leaders felt community policing needed to go beyond meetings and community events and Twitter, even beyond that house on the corner. The philosophy needed to be a part of every interaction, for the well-being of the community and the officers who served them.

“Whether it be a traffic stop, a call for service or even an interaction while walking a beat, the very nature of those interactions can play a role in how community members feel, not just about an officer, but about the department as a whole,” Stamps said.

So when the department chose to revamp its training programs with a renewed focus on community-oriented policing, they added something to the mix: procedural justice.

Community policing 2.0

Procedural justice is community-policing on the front lines, as Stamps put it. It focuses on fostering respect, legitimacy and fairness in every interaction, not just when working on problems or at neighborhood meetings.

“I’ve made it a priority for all of our officers,” Zimmerman said of the philosophy. “I want all of our officers to have the understanding that every interaction that they have should be positive, even if we get called for negative things.”

Chapman, of the federal community policing office, said although community policing may change as departments adapt to budgetary demands, or to make room for other philosophies, the practice is here to stay.

A recent report on best police practices by the President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing echoed that sentiment. Community policing was equated to good policing, and was at the heart of many of the task force’s recommendations, Chapman said.

“It represents the very future of not just where the profession is heading, but where it has to go, particularly in light of recent challenges we’ve seen across the country,” Chapman said. “We need to get back to creating those relationships and reestablishing, enhancing and institutionalizing levels of trust in the communities we serve.”

Recommendations, results

An audit commissioned by the U.S. Department of Justice gave the San Diego Police Department 40 recommendations for improvement following a spate of officer misconduct cases.

1: Draft policy on recruitment, selection, background, investigation and hiring process. Working on it: Department adding policy that pulls from existing manual on process.

2: Update recruitment video presentations and website. Done: Four recruiting videos showcasing diverse officers and assignments were produced, and a 30-minute documentary on San Diego’s policing philosophy and hiring process is in the works.

3: Post minimum qualifications and automatic disqualifiers on recruitment website. Done.

4: Find ways to recruit more diverse applicants that reflect the community. Working on it: The department put job ads in a variety of media in 2014, from movie theaters to newspapers, a marketing plan is in the works, and recruiters went to 30 colleges, 67 community events, and 41 military installations.

5: Expand and diversify the group that sits in on officer interviews. Working on it: The department expanded the panel of department employees who sit in on officer interviews and put together a Hiring Advisory Board comprised of community leaders who will act as potential recruiters.

6: Give all useful documentation about applicants to police psychologists so that a complete assessment about a potential officer’s suitability can be determined. Done.

7: Require two commanding officers to OK evaluations of trainees with performance issues and to give input on trainees’ performance before recruits get final approval. Done: A captain who has been assigned to the training division will coordinate trainee evaluations.

8: Take better advantage of the probationary period for recruits with performance or discipline issues. Done.

9: Implement body-worn cameras as a training tool during field training. Done: Trainees now use mock body-worn cameras to prepare them for using the real thing.

10: Create case studies of criminal sexual assault and other officer misconduct for officer training. Done: City Attorney created training presentation for officers showcasing SDPD criminal misconduct, emphasizing where supervision fell short.

11: Use annual supervisor training on procedural justice to ensure that community members are being treated fairly. Working on it: Emotional intelligence and relationship-building techniques were also added to training.

12: Minimize the use of acting sergeants and work to keep supervisors in charge of the same officers. Working on it: The department has promoted nearly 80 sergeants, which should limit the use of acting sergeants.

13: Consider monthly meetings for patrol division supervisors to reduce the impact of sergeant vacancies in patrol, increase officer supervision and provide mentoring opportunities for new supervisors. Done: Lieutenants have also started meeting more often with sergeants to foster mentoring.

14: Give first-line supervisors more training on accountability and the application of principles of fairness so that officers see discipline consistently applied. Working on it: The department has set up training in this area for lieutenants, captains and new sergeants.

15: Find ways to measure whether officers are using community policing and procedural justice. Working on it.

16: Create a personnel development strategy to retain personnel, perhaps with more mentoring. Working on it: A new training session for supervisors covered how to create development plans and identify opportunities coaching.

17: Consider placing more emphasis on the roles and responsibilities of supervisors. Working on it: The department plans to look into whether those roles and responsibilities need to be revised.

18: Make improvements in handling complaints against officers, and send all positive community feedback to supervisors, who should give feedback to the officers. Done: That’s generally been the practice anyway, department leaders said, but it will be added to the department’s policies and procedures for good measure.

19-25: These seven recommendations relate to the department’s Early Identification & Intervention System, which aims to zero in on problem behaviors in officers early. Working on it: No real changes have been made, but the department said it has done a fair amount of research by reviewing systems used at other police departments and speaking with experts.

26: Provide an unambiguous policy that prohibits the use of alcohol for a specified amount of time before the officer starts a shift. Done: The policy has been revised to read “No alcoholic beverages can be consumed within 8 hours of the officer’s shift.”

27: Implement a truly randomized selection process for drug testing. Done: Officers are no longer told when a new testing cycle has started or concluded.

28: Provide the Citizen’s Review Board with routine updates on the status of complaints received from the board. Working on it: The department has given the board access to a document that lists updates in such investigations.

29: The SDPD should eliminate the Public Service Inquiry process, which was created to document and handle “informal” citizen complaints against officers and gave an “enormous” amount of discretion to supervisors. Done.

30: Return to the process of ranking complaints against officers and then forwarding them to internal affairs. Done.

31: Ensure the discipline process is administered consistently across divisions and that it is as transparent as possible for those within and outside the department. Done: Commanding officers now have a disciplinary protocol to follow.

32: Decisions to veer from the protocol must be described in writing and approved by an assistant chief. Working on it.

33: Work to rebuild trust with the community by focusing on community policing and procedural justice strategies. Working on it: A group of department and community leaders was created to eradicate the “us-versus-them” perspective held by some officers and community members. Also, new training programs teach respect-based policing and emotional de-escalation.

34: Consider setting up a program that helps department officials confront unconscious biases, to address concerns of biased policing. Working on it: The department has crafted a 40-hour training program for officers and supervisors on the topic, and another for recent academy graduates.

35: Give officers opportunities to attend community meetings and engage in problem-solving activities and reduce the time they have to spend on reporting noncriminal and less serious calls. Done: Accommodations will be made to allow officers to attend community meetings in their beat area, and leaders are trying to make filing crime reports online and by phone more efficient.

36: Consider conducting outdoor lineups and community walks with upper-level command staff, and/or inviting community members to stations to attend pre-shift briefings. Done: Every command hosts community walks, and neighborhood leaders are being invited to pre-shift briefings.

37: Consider neighborhood or beat-level “customer” satisfaction surveys and use the results in deciding on patrol priorities. Working on it: Command lieutenants have been randomly contacting citizens about the service they received from officers since May 2014. Findings are reported to department leaders monthly and individual officers receive feedback. A beat level survey is being explored.

38: Develop tailored cultural education involving community leaders and representatives to be delivered during lineup. Working on it: The department has opened its doors to various community groups to provide such cultural education.

39: Develop own citizen’s police academy. Done: The program is called Inside San Diego PD.

40: Update the SDPD website to embody the goals values, and mission of the Department. Working on it.