Women of Their Word

Two counter-culture mavens of Salt Lake City's alternative magazine market reinvent themselves for the digital age.

By Stephen Dark @stephenpdarkOne afternoon in spring 2015, Angela H. Brown stood up in the Miller Business Resource Center in Sandy to give a commencement speech to 80 fellow students. They were graduates of the Goldman Sachs' 10,000 Small Businesses program, and the blue-chip investment bank had asked them to dress as professionals for the occasion. Brown wore a gray dress, matching suit jacket, her mother's pearl necklace and, perhaps as a salute to her punk-rock core, red heels.

For the past 15 years, Brown has been publisher and editor of SLUG Magazine, a monthly, free alternative print and digital publication, the title of which stands for Salt Lake Underground. She told the audience that the three-month course had shown her "I had a problem with fear," whether in terms of taking on loans to grow her business or asking her partner of 10 years to marry her.

The raven-haired Utahn, who sports a tattoo down her back of a Japanese folk art-styled phoenix rising from water, is not the only Salt Lake City counter-culture maven to have sought enlightenment from the global investment bank. Brown encouraged Greta deJong, Salt Lake City's long-standing alternative-lifestyle magazine Catalyst's founder, publisher and editor, to apply.

The irony that the editor of the gritty, punk-rock-born zine and the founder of Salt Lake City's only environmental and holistic-focused monthly turned to one of America's most successful and aggressive multi-billion dollar corporations for help is not lost on either of the longtime friends. deJong wrote in her March 11, 2016, Editor's Notebook, "Business school? For a bleeding liberal magazine editor and publisher? Hell, yeah. I should have done it years ago."

Utah has seen many small publications come and go over the past 50 years, such as the first underground newspaper, Electric News, the Street Paper and the Salt Flat News. Catalyst and SLUG, the longest surviving niche alternative monthlies, launched in 1982 and 1989 respectively.

"That Greta and Angela have survived so long, publishing local monthly magazines is a wonder," says Ken Sanders, veteran book seller and owner of Ken Sanders Rare Books. "It's a testament to the determination and drive of both of these women."

Both were awarded the Josephine Zimmerman Pioneer in Journalism award—Brown in 2013, deJong in 2014—by the Utah chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists, and now each faces the trial of ensuring their publications survive. SLUG and Catalyst, much like every other print and digital publication in Utah, has to address the same challenge: identifying new revenue streams in a world of shrinking print advertising budgets and the Internet.

Brown's response to that challenge, driven by the insights she gained from Goldman Sachs, has been to step down as day-to-day editor—managing editor Alexander Ortega is taking charge—while, as "executive editor" and publisher, she focuses on long-term planning. deJong, by contrast, knew what she had to do before seeking the college's help. According to Catalyst's nonprofit prospectus, "the magazine's long-successful model of providing educational and interpretative news coverage has been only partially successful in adapting to ever-spiraling costs of news print, mailing and other related expenses." So she took the advice of readers and advertisers who said they would be willing to donate funds to keep it going, and turned her 34-year-old magazine into a nonprofit which also allows her to pursue funding through grants.

Brown bought SLUG when she was in her 20s, recalls Utah Film Center's Mariah Mann Mellus, a writer who has scribed a gallery-stroll column for the magazine for 16 years. What was once a punk-rock focused, black-and-white magazine has become, under Brown's stewardship, a boldly colorful, quality-print monthly that encompasses not only local bands but art forms beyond music, action sports and food.

Brown introduced snowboarding, skateboarding, belly dancing and other elements to the magazine that "expanded what underground meant," Mellus says. "SLC Punk had happened—what's our scene now?" Brown grew up and the magazine grew up with her, Mellus says. "Now, she's got mentoring programs for photographers and writers. SLUG has policies and procedures, for heaven's sake. The paper's never looked better."

Under Brown, SLUG went from printing 5,000 copies monthly to 25,000, Brown says. Approximately 150 people are listed on her masthead working at the magazine in some form, many as volunteers as well as a smaller number of freelancers and full-time salaried employees. Brown says that her business model is "based on volunteers looking for experience, resume-building opportunities, a genuine love for community or hoping to interview their musical heroes." Running a publication on good-will, charisma, loyalty and little in the way of a paycheck has its drawbacks, though. Brown couldn't afford health insurance all these years and only got it at age 39 when she got married last year.

With her restructuring in place, Brown hopes to address long-term issues such as monetizing SLUG's website and dealing with rent increases at her downtown Pierpoint Avenue offices, which nearly doubled from $9 a square foot to approximately $16 after property ownership changed. "If you're assigning out stories, it's hard to make time for thinking of the future," she says.

Catalyst's fortunes have been less heady of late, its circulation cut in half from its peak of 30,000 copies distributed monthly in the early 2000s, with the number of ads per issue down from a heyday 160 to 60. deJong "put her heart and soul into that paper," Sanders says. "She kept it going despite the economy." Catalyst has championed everything from the slow-food movement, through environmental issues to mycro-remediation (using mushrooms to battle contaminants in the environment).

For 34 years, deJong has steered her publication, as founder, publisher, editor and columnist. "Catalyst has really been my life. If I ever get a bit bored, I change its size. Or have a big party. Or do something with my hair," she writes in an email.

Catalyst continues to be "like my personal journal," says deJong, 64, in her apartment above the magazine's offices in downtown Salt Lake City. "It's sort of a reflection of where I'm at, what I'm doing."

What unites the two women across their generations—beside both being Capricorns with backgrounds in contemporary dance—is an anchoring passion for the creative and healthy wellbeing of their city.

deJong says when she started Catalyst —dedicated to the idea of "healthy living, healthy planet"—there was a schism between the two populations she was serving, environmentalists and New Age spiritualists. "They were at odds; now they are integrated. I graciously accept any part I played in that happening." Catalyst also provided a platform for the growth of yoga in Salt Lake City and massage therapy. Even though she did not intend Catalyst to carry journalism when she began, it's the stories and the profiles of locals who breathe life into New Age issues and her own fire for such topics that keeps her going after three-plus decades as publisher. Catalyst readers, she says, aren't identified by age, gender or income, but by attitude, "a culmination of personal influences, a values thing."

Brown's husband, artist Fletcher Booth, says Brown sees her role in the community as similar to deJong's. Brown is "trying to make [SLUG] grow, to make it bigger, a more inclusive entity within the community. It's really about that, promoting all the things that are great in the city." Brown, he recalls, talked about leaving Salt Lake City for "a cool city, but then she realized at some point you make the city you live in the city you want it to be."

A CELESTIAL WEDDINGGreta deJong grew up in Neenah, Wis., in the early 1960s, with an older brother who published his own magazine on organic farming called Countryside. That brother infected his younger sibling with a passion to be a magazine editor from her childhood.

Her brother Jerry Belanger "was always her mentor and hero," Catalyst art director and deJong's niece Polly Mottonen says. "She's a little sister, I think that her role in life is to be a proud little sister. She's always rooting for her siblings, her employees and her city."

After graduating from the University of Wisconsin, she worked for two years at Countryside, editing a column of environmental news called Spaceship Earth.

In 1978, deJong followed her then-boyfriend to Salt Lake City where he had found work with a gas company.

Several years later, in 1981, after working in computer sales, she joined forces with two other women, Victoria Fugit and Lezlee Spilsbury, to produce what was initially a monthly guide to community resources, rather than a magazine.

"My friends and I were discovering Native American, Eastern and Celtic spirituality," deJong recalls. People were interested in "real food," moving "back to the land," as the New Age movement became holistic. It was also a time when the few massage therapists in town had to undergo annual VD tests and register with the vice squad, while yoga and meditation were both esoteric pass times few did.

"There was a lot going on, but nobody knew about it," deJong says. "Everything was underground, and there was no way for people to communicate," she says, other than on the bulletin board at the legendary Cosmic Aeroplane bookstore and head shop.

To launch the magazine, in December 1981, the three women threw a party. There were belly dancers, tarot readers, wandering violinists and a church choir in the balcony.

After seven issues, Fugit and Spilsbury moved on, and deJong soldiered on alone, for a while turning the publication into a quarterly.

Greta met her future husband, John deJong, a Vietnam veteran with a degree in industrial engineering, in 1985. He was working on a computer start-up with a friend and was sharing a house with several men who were bicycle couriers. A friend described him as "the next Bill Gates," Greta recalls. He had built a 5-foot-deep, 2,000-gallon concrete hot tub in the backyard—its only rule: no swimsuits—and one day, Greta was invited by others for a dip. The man who did not believe in love at first sight was smitten.

From the start, their emotional relationship was intertwined with business. "He decided he'd much rather work for Catalyst than be a millionaire," deJong says, noting that John brought "political acumen" to the publication. He wrote a column of political commentary called the "Cynicgrill," about a group of characters sitting at a bar. "I feel sad he stopped it. It was so witty and insightful." His current column is "Don't Get Me Started," where he vents on political issues of the day. He is also associate publisher and distributes the paper.

John proposed marriage to Greta in late 1985, and they were married the following March. In her Editor's Notebook entry for March 2007, Greta describes how they were wed in the former Hansen Planetarium on State Street (long since an O.C. Tanner store). "Guests entered through the rings of Saturn. I strode down the side aisle under the constellation of Capricorn. John entered opposite under Leo. ... We said our vows by candlelight."

Despite skepticism that Salt Lake City could support a magazine focused on holistic arts and environmentalism, Catalyst thrived. "Everybody wants clean water and clean air for their grandchildren," she says.

The most important stories Catalyst has done "were related to environmental issues." Now, "there is a broad-based concern for environmental issues," deJong says. "In 1982, it was something for the fringes."

Staff writer Diane Olson joined in 1994. Catalyst was "beautiful and handmade," she says. She immediately penned a number of investigative pieces, including an expose of mismanagement and embezzlement at Tracy Aviary, and a hard-hitting series with John deJong, Greta recalls, on a nerve gas incinerator at Dugway. While the Dugway story was broken by a Deseret News reporter, "we certainly brought in angles that nobody else had," Olson says. "We stirred up a lot of shit."

Another Olson-bylined story that drew plaudits from the Deseret News was a piece on the Bennett Paint building. deJong recalls the glass tower was "a longstanding eyesore." Olson revealed through a title search that it was owned by Sen. Bob Bennett's family. The building was ultimately torn down. Other stories the publisher is proud of include "Karen Denton's story on Kennecott's contaminated groundwater plume seeping out of Bingham Creek" and more recently a piece by Katherine Pioli, also a City Weekly contributor, on hens in city neighborhoods, "which was instrumental in getting laws changed."

Olson, who left Catalyst in 2004 in search of better-paying work than journalism, echoes the description of other staff members of the much-adored deJong. "She's not quite human, she's kind of magical and weird." Come the monthly crunch of going to press, she recalls that often at 3 a.m., as the staff struggled to finish, deJong would be doing handstands. "It was madness, but rather glorious madness," Olson says.

BRIGHT LIGHTS, SMALL CITY

While deJong was a wide-eyed import to Utah, Brown was born and raised in a conservative Mormon household high up in the then-wilds of Emigration Canyon, three miles from Hogle Zoo. Brown was the last of six children and shortly after her birth in 1976, her mother was repeatedly institutionalized with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

Her father was the dean of social work at the University of Utah and an entrepreneur who owned a counseling business specializing in drug and alcohol issues. A portrait of her dad from when he was dean adorns the top of a bookcase in the SLUG offices. "He encouraged me to follow my dreams," she says.

Raised in a "shrouded LDS bubble," Brown's cousin would give her SLUG to read. "There really was another world out there," she learned from its pages, one she believed was the domain of punks she saw hanging around outside the old Crossroads/ZCMI malls, where City Creek Center stands today.

Brown pursued photography, shooting local bands for free for the experience. Then SLUG publisher Gianni Ellefsen hired her to shoot a cover in 1997, and six months later took her on as managing editor.

In 2000, Brown faced a decision. She had always wanted to move to New York City and pursue her dream of being a documentarian and a music photographer. Suddenly she had an opportunity to go to San Francisco as an artist rep for Universal Music. But Ellefsen then offered to sell her SLUG.

She wondered, bright lights, big city or Salt Lake City? Then, she found out her father had been diagnosed with cancer, from which, four years later, he would succumb. She decided to stay near her father and took over SLUG.

One question she had to resolve was her own approach to the magazine's content. One of its former publishers told her, "'I just play God, I put what I like in the magazine.'" While she felt initially disappointed by the seeming lack of an overall philosophy, she later realized, that putting in what she found compelling was "really good advice. This is how you do it."

FROM HUSBAND TO "WASBAND"

Greta deJong's role as a "catalyst" extends beyond her publication. In 1987, she became friends with a woman who had had two miscarriages and was getting a divorce. "I can't wait around for Mr. Right," deJong recalls the woman telling her. "I'm looking for a sperm donor."

After two ectopic pregnancies, deJong knew she wasn't interested in having children. But her husband was still passionate about fatherhood, so she introduced him to her friend as a possible surrogate father. "I felt like I was doing a good deed," she says. The woman wanted "someone who would be acknowledged as the father, whose name was on the birth certificate and show up on bar mitzvahs and birthdays. John agreed to all that." John and Greta accompanied the woman on the first attempt at insemination, holding hands as the doctor went to work under a tent.

Her single-mother friend gave birth to twin girls in 1990, Sophie and Rachel Silverstone. "I conceived of the notion of them," Greta says. "I'm the catalyst to their birth." She also describes it, as "the lazy woman's guide to having kids."

Through the girls' lives, the deJongs would show up sporadically for birthdays and at parties. After the sisters graduated from college, the relationship deepened as they attended events and festivals together, particularly Salt Lake's Burning Man community.

"We started to get to know them better," 25-year-old Sophie says. "They were no longer the quirky couple who enabled our life." The deJongs eventually "emerged as family members, but not like typical parents. Greta was the No. 1 girlfriend I would go out dancing with when I moved home to SLC after college. It was like finding out we had these really fun friends who also happened to be the catalyst to our existence."

Yet, their unconventional marriage eventually came to breaking point. In a March 2007 column, Greta announced she and John had gotten a divorce. "In the last year, our personal work has opened doors that we did not even know were there. I would say that love has survived. The marriage, however, has not."

Greta moved the magazine to the ground floor of what was the couple's home, while John moved to the former offices, taking with him his vast and incalculably complex collection of Lego, Happy Meal toys, lenses and bits and pieces he has doggedly collected over the years. His apartment is somewhere between an antique store and the externalization of the creative impulses of one man's mind. He calls the shapes "space structures. You stretch that, squish it, twist it," he says.

The two years surrounding the divorce were painful for both parties and tense for their magazine colleagues. John deJong says his "love for Greta never wavered." He still reads to her from The New Yorker at night to help her sleep, then returns to the office in the morning with coffee to share with Greta. The man she calls both "a worthy foe," and, in print, her "wasband," is "still sort of my husband," she says. "He introduces me as 'my wife.'" John deJong, she says, "likes to say we're 'cahoots,'" but Greta prefers the term conspirators. "Frankly, I can't imagine Catalyst or my life without him."

BACK SEAT SLUGGER

When 24-year-old Brown took over SLUG, she recalls that it had "a male-dominated culture. The social activists of today would be pissed about the environment. Not a lot of females participated in an active role." She says she doesn't "play into" any bias that others might apply to her gender as a business owner and publisher. In a meeting in a room "full of suits, I can tell if they don't respect my opinion. It doesn't really matter, I don't give a fuck. I'm making a positive change in my community," she says.

But one person's opinion that she did care about was that of artist Fletcher Booth, her next-door neighbor in downtown's ArtSpace apartment complex.

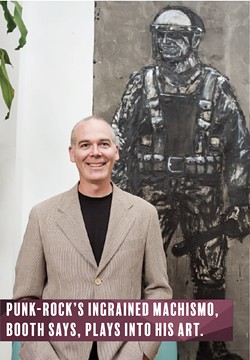

Booth grew up a punk rocker and skateboarder in Kansas, and played cornerback on the high school football team. His subsequent fascination with how hardcore punk was saturated in machismo and with kids growing up in America not knowing where they fit in society, "played a big role in how I approached the aesthetic of my art."

Booth initially thought Brown was a delivery driver for SLUG after he saw bundles of the publication in her backseat. She resembled the punk girls he drew when he was at high school in Kansas. "When I saw Angela, it dawned on me this is the girl I always wanted to meet."

With SLUG making very little money, Brown relied on two other jobs to pay her bills, one of them printing for a photographer from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. It took Booth asking her out seven times, he says, before she was finally able to fit him into her schedule.

Brown started SLUG-branded products, such as the Death by Salt annual music compilations as well as events, most notably Craft Lake City. In 2007, "I started to notice this huge resurgence in the handmade community all over the country, going back to making your own clothes, big craft food, family table movements." In 2009, she organized a SLUG-branded event focused on handcrafts, and eventually launched Craft Lake City as a nonprofit. The event brought together politically diverse vendors at the tables. "You had this dichotomy of a very stereotypical Utah conservative next to a Utah rabble-rouser," she says.

DON'T ASK A COP

As Brown expanded her reach in new directions, a controversy erupted in early 2015 around an anonymously written column in SLUG called "Ask a Cop."

The column began in 2009, Brown says. What intrigued her was that the officer had grown up as part of the Los Angeles punk scene, going to Black Flag and Germ shows. "He came from the same spirit as the magazine came from. I thought it would be really interesting to hear from a like-minded individual who had chosen a career in law enforcement," she says.

Readers' questions for an advice column can be a hit-and-miss affair. So when questions weren't submitted, one of the writers would submit one instead. In the shadow of the Ferguson, Mo., riots, triggered by a cop's shooting of an unarmed black teenager, a SLUG writer asked why cops pursue tactics that lead to people's deaths, rather than use tasers. The cop's response—that tasers kill civilians, too, and cops killed in the line of duty get no attention—provoked criticism from writers and illustrators at SLUG prior to publication. One illustrator resigned over the column.

The column had not received criticism before, Brown says, but with that particular issue, readers, local musicians, artists and others in the community called for a boycott until SLUG stopped publishing "Ask a Cop." Free speech was one thing, responsible publishing another, wrote an activist on Facebook.

Brown agreed to meet with one activist, only to find herself in a confrontation with seven, who "did not want to talk. They wanted a punching bag, to tell me what a horrible, misogynistic, racist person I was," she says.

Brown says the controversy did not impact the magazine financially. While several clients did not renew contracts, others came out in support of SLUG. "It's hard to stand tall on your truth when people throw tomatoes at you," she says.

SCALING DOWN

When Pax Rasmussen first started as deJong's assistant at Catalyst in 2006, the magazine was at 88 pages—currently it's around 40—"and there was a lot more money going through the place." He'd heard the phone ring five or six times a day with someone requesting info about placing an ad. "That just stopped," with the recession, he says. Suddenly all the small businesses that wanted to promote reiki and massages were targeting customers on social media, through Google ads or web apps. "The tiny little businesses just disappeared, they were gone by 2008," he says.

Where there were two full-time sales people when he began, by 2013, Greta was doing the selling. As the magazine shrank in revenue and staff numbers dropped, through mostly natural attrition, "it started to have more of a family business feel," Rasmussen says, with John's daughters working there.

In its 35th year, Greta's frustrations with the limitations of her financial reach remain apparent. "In the years that we are more flush, we are bigger and can encompass more. That's why, right now, I'm not happy being small (the May 2016 issue is 33 pages). There's too much we should be writing about and don't have the wherewithal to cover," she says, ticking off topics such as alternative fuels, solar industry and perma culture that her writers cover, but not in the persistent way she would like.

WEDDING DECONSTRUCTION

In the fall of 2014, Brown attended classes in Goldman Sachs' 10,000 Small Businesses program. She discovered that contrary to her deeply held beliefs that she was fearless, that she could "stand out in a crowd and stand up for myself," fear had "slyly seeped into my life like sticky black tar."

After the course, Brown overcame her fear of asking for money and secured a $100,000 line of credit for her business. She hired four full-time employees and is working on a strategy to dramatically increase SLUG's annual revenue over the next three years, she told her fellow graduates in her commencement speech. That anticipated revenue stream will come from figuring out how to "monetize" SLUG's digital presence, which she has beefed up to include multiple new stories being posted weekly.

Brown also wrought changes at home, proposing marriage to Booth in early 2015.

Brown and Booth decided they wanted their public wedding—they had a secret "official" wedding one month before the event—to deconstruct the nature of the ceremony. One Sunday evening in November 2015, friends, co-workers, artists and local celebrities gathered at the Rose Wagner Performing Arts Center in downtown Salt Lake City.

Longtime Brown friend and fashion designer Jared Gold designed her wedding dress, a startling combination of a U-Haul blanket and a 200-year-old Hungarian piano shawl.

Music was provided by a punk rock karaoke band that played covers of Black Flag, Motorhead and Bad Brains songs. The evening included an analysis of proposals by actor Jason Bowcott, then belly-dancing by a group Brown had danced with for years, followed by a two-minute video filmed by local director Trent Harris of Booth and Brown lip-syncing to a song from Russ Meyer's cult classic "Beyond the Valley of Dolls." Finally KUER 90.1 FM radio personality Doug Fabrizio, in the role of preacher, presented the couple to the gathered crowd.

A QUESTION OF RELEVANCY

For both publications, one ever-present concern is how to remain relevant. "It seems like an uphill battle," says bookstore owner Ken Sanders. "Does the digital age we live in make old, local roots, on-the-ground activism just completely irrelevant, even passé?" he muses.

Brown's leading weapon in the fight for unique, compelling stories is having writers in the community who can identify stories no one else has broken. She continues to try to break into the suburbs, stressing how difficult it is for an independent publication to get readers out in Sandy or Draper, because of all the big-box stores. "We look at how we can infiltrate the suburbs," she says. "That's where all the kids are." She wants to show them, "there's more to life than going to Target on a Saturday and buying shit made in China."

One Catalyst reader wrote to deJong in response to her November 2012 question, "Is Catalyst still relevant?" that the role it played was to find common ground between Utah's two worlds of Mormons and non-Mormons. "And here comes this squeaky little voice in the middle of this political, social stare-down of opposites proposing that it is indeed a common planet and that maybe we could share the beautiful things and somehow make a difference."

To keep that relevancy going, deJong turned Catalyst into a nonprofit, noting that the nonprofit route will mean some limitations, for example, in political expression. But then, she says, "Mother Jones is a nonprofit. If they can cope with the regulations, so can we."

But even if deJong can address her financial woes, there's another challenge ahead. "I need someone to step up to the plate and carry on the art of storytelling," she says.

"Basically, I just want to build a team so that if and when I book, the magazine is still solid." With at least four massage therapy schools in the valley, yoga teachers and meditation fundamental elements of Salt Lake City's culture and health-orientated groceries, Catalyst has played an undeniable role in building a more health-conscious Salt Lake City, as what was once fringe is now mainstream. Such changes, inevitably, herald more businesslike approaches to what were once cottage industries. "An intimacy has been lost," she notes in an email.

Catalyst, deJong believes, continues to find resonance with new generations. She's met many millenials, she says, who reject "the cubicle lifestyle," for the values that are enshrined in her pages. "They're more expressive and liberal than recent generations."

Despite betting on digital for a significant revenue boast—"There's no sense in leaving money on the table," Brown says, quoting her Goldman Sachs' mentor—Brown believes there's a future for print, too. Readers want something that's tactile, she argues. "There's someone somewhere who wants an alternative experience."

More by Stephen Dark

-

Call it a Comeback

Long mired in economic depression, Midvale’s Main Street dusts off its small-town charm.

- Sep 20, 2017

-

Love Letters

Correspondence between a young woman at the Topaz internment camp and her beloved sheds light on Trump's America.

- Sep 6, 2017

-

Triggered

Veterans Affairs exists to help vets. So why did the Salt Lake VA appoint an anti-veteran chief?

- Aug 30, 2017

- More »

Latest in Cover Story

Readers also liked…

-

Forget the family pedigree—Robert F. Kennedy Jr should not be the next president of the United States

Trojan Horse

- Jun 21, 2023

-

Women decry harassment and toxic culture at St. George auto dealership

Men at Work

- Oct 11, 2023