America's Immigration Challenge

Coming to the United States would benefit millions—but policymakers seldom ask whether their arrival would benefit the United States.

On Wednesday, FBI director James Comey alleged that the San Bernardino shooters were already plotting a mass-murder attack on the United States before Tafsheen Malik received the K-1 visa admitting her to the United States. Her husband-to-be, Syed Farook, was born a U.S. citizen. Yet his family’s immigration history should also raise searching questions about the process by which would-be Americans are selected.

Mr. Farook’s father was an alcoholic and could be violent, capable of lashing out at his wife and children, according to statements his mother, Rafia Farook, made in a series of divorce proceedings beginning in 2006. The father, also named Syed Farook, called his wife names, screamed at his children, hurled home appliances and, at the worst moments, grew so combative that his children had to step between him and his wife, she asserted.

The elder Mr. Farook forced his family to move out of their home in 2006, Ms. Farook said in court papers, but he continued to harass her. “My husband is mentally ill and is on medication but is also an alcoholic and drinks with the medicine,” she said. The marriage was formally dissolved this year...

A neighbor, Victor Venegas, said that the elder Mr. Farook had worked for him driving trucks until 2003 and would come around looking for money. “He would sometimes come over without calling,” Mr. Venegas said, and ask, “Can I have $10 to buy cigarettes?”

It’s not clear who exactly provided the first link in the chain of migration that brought the Farook clan to California and ultimately enabled the entry of Tashfeen Malik from Pakistan. That same chain, incidentally, also enabled the migration of Syed Farook’s brother, also named Syed, who volunteered for the U.S. Navy shortly after 9/11 and served aboard the USS Enterprise.

However one assesses that chain and its consequences, it seems clear that the large majority of legal immigrants choose to come—or, more exactly, are chosen by their relatives—for their own reasons. They are not selected by the United States to advance some national interest. Illegal immigrants are of course entirely self-selected, as are asylum seekers. Even the refugee process, reportedly the most tightly screened, operates to a considerable extent outside national control: The first assessment of refugees is typically made by the UN High Commission on Refugees from within camps it operates. That explains why, for example, Christian Syrians make up only about 3 percent of the refugees admitted to the United States, despite accounting for 10 percent of the country’s population: Fearing violence from Sunni Muslims, they apparently hesitate to enter UN camps in the first place.

Donald Trump’s noisy complaints that immigration is out of control are literally true. Nobody is making conscious decisions about who is wanted and who is not, about how much immigration to accept and what kind to prioritize—not even for the portion of U.S. migration conducted according to law, much less for the larger portion that is not.

Nor is there much understanding of what has happened after it has happened. A simple question like, “How many immigrants are in prison?” turns out to be extraordinarily hard to answer. Poor information invites excessive fears, which are then answered with false assurances and angry accusations.

Nervous about Syrian refugees in the wake of the Paris massacre? How dare you! Would you turn away Jews fleeing Hitler? Oh, you think that analogy is hyperbolic? Tell it to the mayor of New York City.

This frequent invocation of the refugee trauma of the 1930s shuts down all discussion of anything that has happened since. Since 1991, the United States has accepted more than 100,000 Somali refugees. Britain accepted 100,000 as well. Some 50,000 Somali refugees were resettled in Canada; some 40,000 in Sweden; smaller communities were settled in the Netherlands, Norway, and Denmark.

How’s that going?

- Minnesota is home to America’s largest Somali community, 33,000 people. The unemployment rate for Somali Minnesotans in 2015 was triple the state average, 21 percent. As of 2014, about 5,950 of the state’s Somali population received cash assistance; 17,000 receive food assistance as of 2014.

- A close study of Somali refugees by the government of Maine (home to the nation’s second-largest Somali community) found that fewer than half of the working-age population had worked at any time in the five years from 2001 through 2006.

- The U.S. unemployment rate of 20+ percent still represents a huge improvement over rates in Europe. Only about 40 percent of working-age Somali men in Norway are employed. In the Swedish city of Malmo, home to one of the largest Somali communities in Europe, only 20 percent work.

- Somalis have so much difficulty finding work in the developed world because their skills badly mismatch local labor needs. Only about 18 percent of boys and 15 percent of girls attend even primary school in Somalia. UNICEF has given up trying to measure literacy rates. Much of the U.S. refugee population is descended from people held as slaves in Somalia, who accordingly lack any family tradition of education. Their children then flounder in Western schools, baffled by the norms and expectations they encounter there. In the U.K., Somali students pass the standard age 16 high school exams at a rate less than half that of Nigerian immigrant students.

- Struggling with the transition from semi-nomadic-herder society to postindustrial urban life, young Somalis in the West are tempted by criminal activity. Danish Somalis are 10 times more likely to be committed of a serious offense than native-born Danes. At least 29 young Canadian Somalis were murdered in drug-trafficking-related deaths between 2005 and 2010. In July 2012, Richard Stanek, sheriff of the county that encompasses Minneapolis-St. Paul, testified to Congress about the rising danger of American Somali gangs. While stressing that most Somalis in Minnesota obeyed the law, Stanek worried:

Somali gangs have emerged as a serious threat to community safety both in Hennepin County and as a unique challenge to our law enforcement re- sources. These gangs are involved in multiple criminal activities that require sophisticated and resource-intensive law enforcement investigations. They are growing in influence and violence … and practice certain cultural behaviors that render some traditional U.S. criminal justice tools less effective.

- Other young Somalis turn to political and religious violence. An estimated 50 American Somalis returned to fight for al Shabab, committing some of the most heinous acts of that insurgency. One carried out a suicide bombing that killed 24 people in 2009. Al Shabab claimed three American Somalis took part in the attack on Nairobi’s Westgate shopping mall in 2013 that killed at least 67 people. Al Shabab is now intensely recruiting American Somalis to undertake terror missions inside the United States.

We call upon our Muslim brothers, particularly those in the West... imagine what a dedicated mujahid (fighter) in the West could do to the American and Jewish-owned shopping centers across the world.

What if such an attack was to call in the Mall of America in Minnesota, or the West Edmonton Mall in Canada? Or in London’s Oxford Street, or any of the hundred or so Jewish-owned Westfield shopping centers dotted right across the Western world...

Immigration advocates understandably prefer to focus on the contributions of the refugees from Nazism than on less successful and more recent experiences.

Yet surely it is the more recent experiences that are more relevant. Pre-civil war Syria was no Somalia, but it was very far from a developed country. In 2010, the average Syrian had less than six years of schooling, less even than Egypt, according to the UN Development Index. Women were systematically subordinated: Only a quarter of Syrian women completed secondary education; only 13 percent participated in the workforce. Few Syrians will arrive with the skills of a modern economy, even apart from the language gap. Before the civil war, almost one-fifth of Syrians worked as agricultural laborers; about one-third worked in Syria’s notoriously inefficient public sector.

How will these new arrivals adjust to the very different job markets of Western Europe and North America?

The European environment will prove especially challenging. Totaling benefits, mandated vacations, and so on, employers in the German private sector paid an average of 31.80 euros per hour per worker. And Germany—as expensive as it is—is actually one of the cheaper places to do business in Europe. The average French private sector employee costs 35.20 euros, the average Dane in the private sector, 42.0 euros. The cost of labor explains why such familiar American jobs as parking lot attendants, food runners in restaurants, and so on seem hardly to exist in northern Europe. It also explains why workers who cannot generate more than 31.80 euros in value for a business languish in protracted unemployment.

Germany in particular has tried to cope with this challenge by aggressively promoting low-wage work for the benefit of workers in the former East Germany and new immigrants. Some categories of work are exempted from standard benefit packages and minimum wage laws. But if first-generation migrants willingly accept this bargain, their children likely won’t. Unfortunately, while a new population’s expectations will rise in one generation, the accumulation of sufficient human capital to fulfill those expectations takes significantly longer. The predictable result: protracted underemployment across visibly identifiable subgroups of the population—group perceptions of inequity and injustice—resentment, radicalization, and criminal and political violence: the second-generation European Muslim experience in a one grim economic equation.

For better or worse, producing low-wage jobs is one thing the U.S. economy can do in abundance. Where Americans have more difficulty is offering a path to upward mobility, especially for people born into the poorest one-fifth of the population. Not all migrants inhabit that bottom one-fifth. But disconcertingly many do—and contra the American Ellis Island myth, their children then stick there. America’s poor immigrants don’t usually arrive as refugees, of course. That distinction acquires great urgency in polemic. It has little meaning in real life.

If a refugee is someone “pushed” from his or her native land, and an immigrant is one “pulled” to a new country, then the vast majority of the tens of millions of people seeking to move from the poor global South to the rich North belong to both categories.

The tens of thousands of youthful border-crossers who claimed asylum in the United States in the summer of 2014 were described by supporters as refugees from gang violence at home in Central America. Yet 2014 was a year in which gang violence dramatically abated in Honduras and Guatemala. The “push” was stronger two years earlier ... but the surge responded to the “pull” of perceived opportunity.

Even with the Syrian refugees, “pull” matters as much as “push.” Most of the Syrians en route to Europe are immediately fleeing—not the dictator Assad’s barrel bombs—but the tedium and futility of Turkish refugee camps. When European border controls collapsed in the fall of 2015, Syrians and those claiming to be Syrian rushed, not to any European country at random, but very specifically to the countries with the strongest job opportunities and most generous welfare systems: Germany and Scandinavia. Every day, at the entrance to the Channel Tunnel, young men described as “refugees” risk their lives to reach Britain from ... France.

The distinction between migration and asylum-seeking is grounded less in differences of motive, and more in an artifact of international law. Shamed by the exclusion of German and Austrian Jews in the 1930s, the post-World War II democracies signed treaties and conventions that conferred rights of asylum on persecuted people. If a person who wishes to resettle in one country can gain recognition as an asylum-seeker, he cannot easily be removed. Virtually all of the 51,000 Central Americans who jumped the border in 2014 still remain in the United States. The tens of thousands of Mediterranean crossers who falsely claimed to be refugees when they disembarked in Italy likewise mostly remain in Europe.

The immigration debate is defined by legal categories: migrant versus refugee; illegal versus legal. Those legal categories are subordinated, however, to a central political division: migrants who are chosen by the receiving country versus those who choose themselves. That political division in turn is connected to a fateful economic division: migrants who arrive with the skills and attitudes necessary to success in a modern advanced economy versus those who don’t.

Those divides are highlighted by a massive new study by the National Academy of Sciences of the acculturation of new immigrants to the United States: “The Integration of Immigrants into American Society.” The first reports on the study in October headlined comforting news: recent immigrants to the United States were assimilating rapidly—arguably more rapidly than their predecessors of the pre-1913 Great Migration. One must read deeper into the report to encounter the worrying question: Assimilate to what? Like the country receiving them, immigrants to the United States are cleaved by class. Approximately one quarter of immigrants arrive with high formal educational qualifications: a college degree or more. Their record and that of their children is one of outstanding assimilation to the new American meritocratic elite, in many ways outperforming the native-born. (The highest outcomes are recorded for immigrants from India: 83 percent of male immigrants from India arrive with a college degree or higher.) College-educated immigrants are more likely to be employed than natives, and their children are more likely to complete a college degree in their turn. Here is a mighty contribution to the future wealth and power of the United States.

By contrast, about one-third of immigrants arrive with less than a high-school education. Immigrants from Latin America—the largest single group—arrive with the least education: Only about 13 percent of them have a college degree or more. They too assimilate to American life, but to the increasingly disorderly life of the American non-elite. Their children make educational progress as compared to the parents, but—worryingly—educational progress then stagnates or retrogresses in the third generation. For many decades to come, Latino families educationally lag well behind their non-Latino counterparts. The static snapshot is even more alarming: While 60 percent of Asian Americans over age 25 have at least a two-year diploma, as do 42 percent of non-Latino whites and 31 percent of African Americans, only 22 percent of Latino Americans do.*

Partly as a result, as David Card and Stephen Raphael observe in their 2013 book on immigration and poverty, even third-generation Hispanic Americans are twice as likely to be poor as non-Latino whites.

When children of immigrants grow up poor, they assimilate to the culture of poorer America. While Mexicans in Mexico are slightly less likely to be obese than Americans, U.S. Latinos are considerably more likely to be obese than their non-Latino counterparts. The disparity is starkest among children: While 28 percent of whites under 19 are obese or overweight, 38 percent of Latino children are. American-born Latinos likewise are more likely to have children outside marriage than foreign-born Latinos.

This downward assimilation has stark real-world consequences. U.S.-born Latinos score lower on standardized tests and are more likely to drop out of high school than their non-Latino white counterparts. While those Latinos who do complete high school are slightly more likely than non-Latino whites to begin college, they are less likely to finish. Starting school without finishing burdens young people with the worst of all educational outcomes: college debt without a college degree.

About half of all immigrant-headed households accept some form of means-tested social welfare program. Those immigrant groups that arrive with the most education are, unsurprisingly, the least likely to require government assistance; those with the least require the most. Only 17 percent of households headed by an Indian immigrant use a means-tested program; 73 percent of households headed by a Central American immigrant do. (It’s important to look at whole households because while undocumented immigrants who head a household may not be eligible for many means-tested programs, their U.S.-born children are.)

While Mexican immigrants are less likely to be sent to prison than the native-born, U.S.-born Hispanics are incarcerated at rates 50 percent higher than their parents and grandparents—and almost double that of U.S.-born whites.

In other words, immigrants to the United States are dividing into two streams. One arrives educated and assimilates “up”; the other, larger stream, arrives poorly educated and unskilled and assimilates “down.” It almost ceases to make sense to speak and think of immigration as one product of one policy. Without ever having considered the matter formally or seriously, the U.S. has arrived at two different policies to serve two different sets of interests—and to achieve two radically different results, one very beneficial to U.S. society; the other, fraught with huge present and future social difficulties.

How did this happen? Almost perfectly unintentionally, suggests Margaret Sands Orchowski in her new history, The Law That Changed the Face of America. The Immigration Act of 1965 did two things, one well understood, one not: It abolished national quotas that effectively disfavored non-European immigration—and it established family reunification as the supreme consideration of U.S. immigration law. That second element has surprisingly proven even more important than the first. A migrant could arrive illegally, regularize his status somewhere along the way—for example, by the immigration amnesty of 1986—and then call his family from home into the United States after him. The 1965 act widened the flow of post-1970 low-skilled illegal immigration into a secondary and tertiary surge of further rounds of low-skilled immigration that continues to this day.

Americans talk a lot about the social difficulties caused by large-scale, low-skill immigration, but usually in a very elliptical way. Giant foundations—Pew, Ford—spend lavishly to study the problems of the new low-skill immigrant communities. Public policy desperately seeks to respond to the challenges presented by large-scale low-skill immigration. But the fundamental question—“should we be doing this at all?”—goes unvoiced by anyone in a position of responsibility. Even as the evidence accumulates that the policy was a terrible mistake from the point of view of the pre-existing American population, elites insist that the policy is unquestionable ... more than unquestionable, that the only possible revision of the policy is to accelerate future flows of low-skill immigration even faster, whether as migrants or as refugees or in some other way.

Even as immigration becomes ever-more controversial with the larger American public, within the policy elite it preserves an unquestioned status as something utterly beyond discussion. To suggest anything otherwise is to suggest—not merely something offensive or objectionable—but something self-evidently impossible, like adopting cowrie shells as currency or Donald Trump running for president.

Only Donald Trump is running for president—and doing pretty well, too. He’s led polls of Republican presidential candidates for now nearly 5 consecutive months. Pundits (including me!) who had insisted that it was impossible that he could actually win the nomination are now beginning to ponder what will happen if he somehow does. And while it’s clear that the immigration issue does not constitute all of Trump’s appeal, it’s equally clear that the issue has been indispensable to that appeal.

Until this very year, Trump’s few sparse comments on immigration fell neatly within the elite consensus. In a December 2012 Newsmax interview, Trump blamed Mitt Romney’s recent presidential defeat on Romney’s “self-deportation” comments. Trump endorsed the then conventional that the GOP’s immigration message had been “mean-spirited” in 2012 and invite more people to become “wonderful, productive citizens of this country.”

What seems to have changed Trump’s mind is a book: Adios America by Ann Coulter. The phrase “political book of the year” is a usually an empty compliment, but if the phrase ever described any book, Adios America is it. In its pages, Trump found the message that would convulse the Republican primary and upend the dynastic hopes of former-frontrunner Jeb Bush. Perhaps no single writer has had such immediate impact on a presidential election since Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Adios America is an avalanche of an essay, a cascading torrent of quips, facts, and statistics. Furiously polemical, mercilessly indignant, utterly indifferent to balance and context, Coulter batters the reader with what might be called the “reverse valedictorian”: instead of the usual heartwarming stories of immigrant success, she immerses the reader in incidents of immigrant crime, failure, and welfare abuse.

A Chinese immigrant in New York, Dong Lu Chen, bludgeoned his wife to death with a claw hammer because she was having an affair. He was unashamed, greeting his teenaged boy at the door in bloody clothes, telling the boy he had just killed mom. Brooklyn Supreme Court Justice Edward Pincus let Chen off with probation—for murder—after an anthropologist testified that, in Chinese culture, the shame of a man being cuckolded justified murder ... The female head of the Asian-American Defense and Education Fund, Margaret Fung, applauded Chen’s light sentence, saying that harsher penalty would “promote the idea that when people come to America they have to give up their way of doing things. That is an idea we cannot support.” At least Chen came to the United States based on his specialized knowledge of nuclear cell extraction biology. No, I’m sorry—Chen emigrated to the United States with his entire family when he was fifty years old—fifteen years away from collecting Social Security—to be a dishwasher.

Two of the most famous murder sprees of the 1990s were also perpetrated by legal immigrants. The 1993 Long Island Railroad massacre that left six passengers dead was committed by Jamaican-immigrant Colin Ferguson ... In 1997, Christopher Burmeister, a twenty-seven year old musician, was shot in the head and killed by Palestinian immigrant Ali Hassan Abu Kamal at the top of the Empire State Building. Burmeister’s band mate, Matthew Gross, also took a bullet to the head but—after eight hours of surgery—survived. Gross now lives in a group home in Montclair, New Jersey, with other brain-damaged men, taking daily medication for his seizures. The assailant, Abu Kamal, had immigrated to America with his entire family two month earlier—at age sixty-eight. It’s a smart move to bring in older immigrants well past their productive years, so we can start paying out Social Security right away.

Coulter’s core message, “immigration isn’t working as promised,” is joined to a second message equally central to the Donald Trump campaign: “We are governed by idiots.”

Those are messages that resonate only louder after the San Bernardino massacre, in which one of the killers entered the country on a fiancée visa issued to a nonexistent address in Pakistan.

But the truth is actually far scarier: No, America is not governed by idiots. It’s governed mostly by capable and conscientious people who are simply overwhelmed by the scale of the immigration challenge. The UN High Commission on Refugees estimates that 60 million people have been displaced by war or natural disaster. Millions of them would wish to move to Europe or North America if they could. That population will only grow in the years ahead: Nigeria, a country of an estimated 137 million people today, is projected to reach 400 million within the next 35 years, overtaking the United States. How many of them will wish to leave behind their failed state for opportunities in the global North? Even in Mexico, a middle-income country by global standards, more than half of young people in their 20s would like to move to the United States if they could.

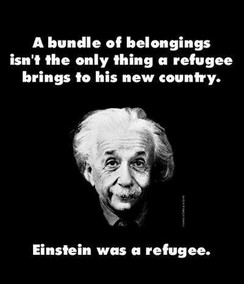

One reason we hear so much about the Jewish refugees of the 1930s, to circle back to where I started, is the natural human tendency to wish away overwhelming problems. If the word “refugee” conjures up Albert Einstein, Kurt Weill, Hans Bethe, Lawrence Tribe, Billy Wilder, and Henry Kissinger—well, what country wouldn’t welcome as many as it could get?

But that’s not the story of Syria. Syria is embroiled in a civil war with hundreds of thousands of combatants. Most of the killing has been done by the army of President Bashar al-Assad and now, his Iranian and Russian allies. President Obama said at his November 16 press conference in Antalya, Turkey, “We also have to remember that many of these refugees are the victims of terrorism themselves—that’s what they’re fleeing.” Many of his hearers mentally amended the president’s words to a claim that the Syrian refugees are fleeing the terrorism of ISIS. But this president always speaks carefully, and that’s not what he said, even if he didn’t mind being misheard. Interviews with the refugees themselves confirm that most are fleeing the violence perpetrated by the Assad regime, not the deranged fanaticism of ISIS. While comparatively few Syrians—or Muslims anywhere—have any sympathy for ISIS ideology, the majority of Syrians espouse some form of Sunni fundamentalist religious belief, a fundamentalism that Western societies asked to open their doors are entitled to find disquieting.

Also disquieting is the way in which refugee advocates toggle back and forth between reassuring the West that there is nothing to fear—and warning of terrorist violence if the refugees are refused. Here’s Michael Ignatieff, a noted writer on refugee issues and former leader of the Liberal Party of Canada in The New York Times in September:

What must Syrians, camped on the street outside the Budapest railway station, be thinking of all that fine rhetoric of ours about human rights and refugee protection? If we fail, once again, to show that we mean what we say, we will be creating a generation with abiding hatred in its heart.

Ignatieff is right to express concern about the hatred sweeping the Middle East. But to many Americans—and Canadians too, and Europeans, and other Westerners—it may seem reckless to respond to that hatred by inviting more of it into their own countries, and more reckless than ever after the Paris and San Bernardino jihadist atrocities. Obama and much of the elite media find that reaction cowardly, contemptible and even “shameful”—his word. But in a democracy, leaders who dismiss and denigrate widespread concerns soon find themselves ex-leaders. Everywhere in the Western world there is a fast-growing constituency for new kinds of immigration and refugee policies. If anything is shameful, it is the shabby, thoughtless, and arrogant elite consensus that has to date denied that constituency a responsible political leadership. But that too is changing, yielding to heavy evidence and hard experience.

* This article originally stated that a National Academy of Sciences report found that the large number of Latino immigrant teachers with poor English-language proficiency is one cause of the academic difficulties among the immigrant children they teach. In fact, the report found that teachers serving immigrant students with limited English proficiency are less experienced and report feeling less prepared than teachers serving students who are native born. The report did not comment on English-proficiency rates among teachers who serve immigrant students, and it noted that the relative scarcity of Latino teachers may impede communication with parents. We regret the error.