Ryan Coogler’s rollicking reboot of the Rocky series, Creed, stars Michael B Jordan as Adonis Johnson, the son of heavyweight boxer Apollo Creed (former arch-nemesis of Rocky Balboa). Adonis, a child from an extra-marital affair, never met his father – in fact, he came into the world shortly after Apollo was squarely walloped through the pearly gates by Soviet propaganda pugilist Ivan Drago in 1985’s Rocky IV.

Having been rescued from juvenile detention by Apollo’s widow (Phylicia Rashad), Adonis grows up to be a complex character: a well-paid, white collar LA drone by day, and a hardcore slugger on Mexico’s illegal boxing circuit by night. He eventually quits his job, and decamps to Philadelphia in order to persuade a reluctant Rocky – now a restaurant manager – to train him. Understandably and predictably, Adonis wants to escape his father’s shadow, and establish his own unique legacy as a fighter.

On the surface Coogler’s Creed is anything but radical. The director wisely refrains from reinventing the wheel, instead harnessing the earthy qualities that made the franchise’s first films so successful. As in countless sports movies, the protagonist undergoes crises of faith on his journey toward spiritual nourishment and the American Dream.

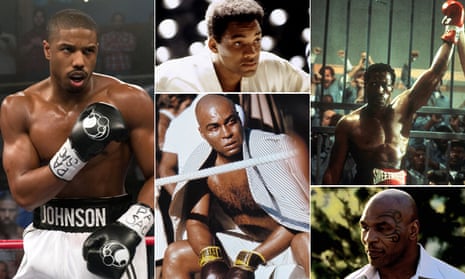

Yet despite its familiarity, Creed also feels quietly revolutionary. Its groundbreaking feature isn’t that complex: Coogler simply presents us with a genuine rarity, a black boxing hero on the big screen.

Granted, Hollywood has given us prestige documentaries like classic When We Were Kings (1996), about the 1974 Rumble in the Jungle between Muhammad Ali and George Foreman; and biopics of black boxers in the form of Norman Jewison’s moving The Hurricane (1999), about the wrongfully imprisoned Rubin Carter, and Michael Mann’s stately, if slightly stodgy Ali (2001). But even though black boxers dominated the sport for a significant chunk of the 20th century – black fighters held an almost total stranglehold on the heavyweight title, with a handful of exceptions, from Joe Louis in the 1930s to the Klitschko era of the last decade – the statistics have not been reflected in cinematic representation.

Boxing scholar Georg Bauer has argued that in US boxing films the protagonist’s ethnic background is less reflective of reality, geared instead toward public wish fulfillment. The wild box office success and public fascination with Rocky Balboa, the consummate underdog, is a great example: when the film was released in 1976, there hadn’t been a white American heavyweight champion since Rocky Marciano in 1956.

Sports Illustrated’s list of 50 Greatest American Boxing Movies includes many undisputed classics (City Lights, Fat City, Raging Bull), but only a paltry two feature fictional black protagonists. Both offer compelling insights into boxing’s intensely racialised history. One is The Great White Hope (1970), in which an Oscar-nominated James Earl Jones plays Jack Jefferson, a thinly veiled version of Jack Johnson, who became the first African American world heavyweight boxing champion at the height of the Jim Crow era. Described by writer John Ridley as “a guy who basically lived his life with a metaphorical middle finger raised in the air”, Johnson openly dated white women in a time of miscegenation laws, and faced appalling discrimination: he received a year-and-a-day sentence for transporting a minor across state boundaries. Johnson was convicted under the Mann Act, legislation supposedly designed to protect young women, but in this case pointedly directed at him. The film’s title comes from the phrase coined by writer Jack London to describe a white fighter who might step up to combat the monstrous black affront to the perceived superiority of the Caucasian race.

The other film on the list is Reginald Hudlin’s heavy-handed satire The Great White Hype (1995), an intermittently amusing take on the racialised machinations informing primetime boxing. Damon Wayans plays a flashy, Tyson-esque heavyweight champ, but the real star of the show is a bewigged Samuel L Jackson as shady Don King-a-like Rev Sultan. Its plot was inspired by Larry Holmes’s 1982 fight with Gerry Cooney, and Tyson’s 1995 comeback fight against Peter McNeeley; the racial conflict angle of both contests was played to the hilt by media and promoters alike. Unlike Creed, which reverberates with hope and vibrancy, these films are infused respectively with tragedy and bleak cynicism.

One might argue that Apollo Creed bucks the trend. And it’s true that “The Master of Disaster”, as essayed by Carl Weathers from Rockies I-IV, was a raffishly charismatic foil to the “Italian Stallion”. But he ultimately proved dispensable, always played second fiddle, and before he became Rocky’s trainer, was deliberately characterised as an uppity, preening buppie. Meanwhile, in Clubber Lang (Mr T), Rocky III featured one of the most crass racial stereotypes of all: an egotistical, animalistic brute.

Lang’s propensity for brutality may have been a partial nod to the blaxploitation film genre which proved so popular in the 1970s. These cheaply made money-spinners featured black actors in overtly masculine and sexual roles, with agency, for the first time in Hollywood history. Boxing and blaxploitation, unsurprisingly, went hand in hand. Ken Norton began appearing in films, including the infamous Mandingo, at the height of his boxing career (He would later pull out of playing the role of Apollo Creed). Former footballer Fred Williamson chewed up the screen as the eponymous Hammer (1972), a mafia-sponsored pugilist who rises through the ranks and ends up facing a serious moral dilemma. Meanwhile, Jamaa Fanaka’s Penitentiary series – a gaudy trilogy of prison boxing films – made an underground star of Leon Isaac Kennedy, who in 1981 remade Body and Soul featuring a cameo from Muhammad Ali.

The Penitentiary films get progressively weirder as they go along – the third instalment (1987) sees Kennedy, as “Too Sweet” Gordone, forced to fight the prison’s most feared killer, a bondage gear-clad, flying dwarf rapist named Midnight Thud (this scene truly must be seen to be believed.) These rambunctious prison boxing flicks served as a clear inspiration for Walter Hill’s enjoyably grimy Undisputed (2002), in which undefeated inmate Monroe Hutchens (Wesley Snipes) faces off against a new arrival: convicted rapist and deposed world champ George “Iceman” Chambers (Ving Rhames). (In an interview, Hill said: “Naturally we need black men to give this movie serious credibility.”)

Elsewhere, when it comes to portraying black characters, American boxing movies largely reflect a wider trend in the national cinema: to prioritise the stories of white characters in a bid to “cross over”. This is true for films like Diggstown (1992), a fun con thriller that’s more interested in the shenanigans of a career trickster (James Woods) than it is the ageing boxer at the heart of the scam, played with heart and great physicality by Louis Gossett Jr, sprightly at 56. It’s also true for films like Against The Ropes (2004), where Omar Epps is the robust athlete playing second fiddle to Jackie Kallen (Meg Ryan), the first woman to find success as a boxing promoter; and Resurrecting the Champ (2007), a drama based on the true story of a homeless African American man (a grizzled Samuel L Jackson) who may or may not have been a former contender for the heavyweight title. The story is entirely framed through the lens of a white investigative journalist played by Josh Hartnett.

Intriguingly, though, issues of race and colour are ostensibly incidental to Creed. Coogler does include some racial commentary. There’s the shocking opening shot of six black boys, shackled and shepherded through stark juvie halls, which immediately places the film in the real-world context of the disproportionate incarceration rate of African American youth. Generally though, in Creed’s universe, intra-ethnic harmony is the order of the day.

The film is more notable for its cultural specificity, and keenly observed portrait of modern, young, black American life, which shouldn’t feel as blissfully refreshing as it does in 2015. There’s a beautiful, tender sequence in which Adonis braids his girlfriend Bianca’s hair, while in the most exhilarating sequence (a nod to a similar moment in Rocky II), a group of black kids ride dirt bikes through the street behind Adonis while Lord Knows by Philly rapper Meek Mill judders on the soundtrack.

Perhaps most exciting is the pairing of star Jordan and director Coogler – their second consecutive collaboration following the Sundance-award winning Fruitvale Station – which has the makings of a brilliant combination: the putative, African-American answer to Martin Scorsese and Robert De Niro, who took on boxing with Raging Bull. It’s a tantalising prospect, and Creed feels like both a breath of fresh air and a breakthrough for representation in boxing films.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion