EU rules governing the checks that UK authorities can make on doctors still have major weaknesses seven years after a patient safety scandal revealed catastrophic flaws in the system, according to Britain’s medical regulator.

Niall Dickson, chief executive of the General Medical Council (GMC), said it must have the same powers to check the competence and medical skills of doctors from Europe as it already does for medics from the rest of the world.

Moves to introduce digital “passports to practise” for EU doctors could make matters worse, Dickson said, and “jeopardise our ability to protect patients in the UK”. The language checks the GMC can make on EU doctors would be the last line of defence.

He said: “We are also calling on the UK government to include patient safety considerations in their negotiations on the future UK membership. A commitment to improve patient safety should be part of any continued membership of the EU.”

There are fears the system of checking doctors’ skills, competence and medical background could be made worse with the proposed European professional card (EPC), which will shorten the time taken to register doctors, according to the GMC.

This is to be introduced for nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists, estate agents and mountain guides from January. Cards for doctors are expected to follow in 2018. The GMC said there must first be a full independent assessment of how the e-cards for the professions have worked, even though other checks, including of language ability, will still be undertaken before a licence to practise in the UK is issued.

Dickson said: “It must be right that every country in the EU should be able to check that those coming to work within their borders have the competency, skills and cultural understanding to treat its patients safely.”

At present, all doctors are required to apply for registration, usually online. They must provide evidence in person of identity including a photograph taken within the last three months, plus their qualifications, training and their ‘good standing’. They must also must give evidence their skills and knowledge are up to date.

To get a licence to practise , they must also give evidence of their recent employment. Since last year, EU doctors applying to work in the UK have had to provide evidence of their English language skills before being allowed a licence to practise. The requirements for doctors from elsewhere in the world are tougher.

They must undergo English tests and a three-hour written exam in their home country or in the UK, before facing a day at the GMC’s clinical assessment centre, where their identity and credentials are checked. They then undergo a series of 16 five-minute mini-exams, including tests in skills such as taking a patient’s history, making a preliminary diagnosis, knowing what tests might be needed and communicating with patients,which might include delivering bad news.

The GMC’s call for national regulators to have more powers follows revelations that checks on EU doctors’ English language ability introduced in June last year have so far resulted in more than 900 medics, nearly half the total seeking a UK licence to practise, failing to show they have the necessary knowledge.

This can be done by their having studied medicine on courses predominantly in English, via professional references, or by taking approved English language tests.

The GMC is also taking action against EU doctors already working in the UK. Last month one was suspended and another forced to work under supervision and retake an English test by the Medical Practitioners Tribunal Service (MPTS), which is part of the GMC but makes its decisions independently. Other disciplinary cases are in the pipeline.

The English checks were made possible by changes in EU regulations that allowed the UK to demand evidence not only from doctors from member states, but also those from Iceland, Norway, Liechtenstein and Switzerland.

However, granting the UK regulators, or those in other countries, further powers to test competence and skills would likely be seen elsewhere as striking at the heart of the core EU principle of freedom of movement.

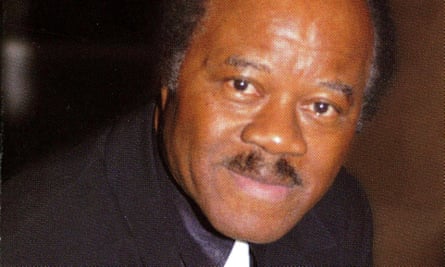

The GMC first demanded competence tests on all doctors from outside the UK in 2009, following an incident in February 2008 in which the German locum GP, Daniel Ubani, accidentally killed David Gray, 70, by giving him an overdose of a painkiller at his Cambridgeshire home.

Guardian inquiries showed that flaws in the NHS’s own employment checks had given Ubani his ticket to work in England.

Dickson’s remarks came as the GMC published its 2015 report on the state of medical education and practice. It shows a sharp increase in the number of doctors coming to the UK from some European countries.

About 24,000 doctors working in the UK, about 10% of the total, qualified elsewhere in Europe. Medics from countries with high unemployment, such as Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain, increased by over 2,100, more than a third, between 2011 and 2013.

Dickson said: “This is about protecting patients and making sure doctors are competent. The EPC hands over the responsibility for these checks to the regulator in the country where the doctor is coming from. There are real advantages in free movement around Europe but this process assumes that every regulator will apply the rules in the same way and with the same rigour. They don’t, and this worries us,” Dickson said.

“We deal with applications to work here quickly and efficiently, but some cases can be more complex and we don’t want a situation where a doctor demands to go on the register and can start practising before we have had time to complete the necessary checks. We are worried that something will go wrong if we are not able to do what we need to do,” said Dickson.

“We would like to see a position in Europe where all national authorities can check both the competence and language ability of any doctor seeking to work in that country ... We have long argued for this change, but now there are aspects of the new legislation which we fear will make the situation worse.

“In the last year we have shown with the introduction of checks on language skills that checks are needed. We are definitely not there as far as competence is concerned and this means there is still a significant and unacceptable gap in our regulatory defences.“We are not against doctors who have qualified in Europe. The vast majority are providing a good service and they are perfectly good and perfectly able. But I am sure most European citizens would want assurance that the doctors coming into their own countries would match the standards of their home-grown doctors.”

Employers too had a responsibility, Dickson said. “They cannot rely on GMC registration alone and must satisfy themselves both on the language skills and competency of any doctor they employ.”

The latest figures for non-European trained doctors from elsewhere in the world show there were 57,400 licensed to work in the UK. Last year, about a third of those taking competency tests on applying failed.

In 2014, 267,000 doctors were on the UK medical register, of whom about 237,900 had a licence. A third of those licensed had done the bulk of their medical training outside the UK, showing just how much the country relies on foreign doctors.

The Department of Health (DH) did not comment on Dickson’s appeal for the government to continue fighting for the GMC to be able to test the competence of EU doctors. It too emphasised the need for employers to make their own checks and said the European commission had promised an early review of the professional card before it applied to doctors.

A DH spokesperson said: “To work in the UK, all doctors, including those from abroad, must be registered with the GMC. What’s more, we expect all employers to carry out appropriate pre-employment checks to make sure their doctors are capable of providing the best care.

“The European professional card is an additional route that medical staff will be able use to recognise their qualifications if they choose to do so.”

A spokesperson on the internal market for the European Commission insisted the EPC would not change the division of responsibilities between home and host member states. Host states including the UK remained responsible for taking the decision on issuing the EPC.

“If necessary, the host member state can also request any necessary additional information from the home member state or directly from the applicant in order to take its decision. The relevant procedural deadlines may be extended pending receipt of such information and positive, negative or decisions requesting the imposition of compensation measures are always possible within the deadlines.”

Extensive consultations would take place before the EPC was extended to doctors and others.

The process would have no impact on supervisory powers over professionals outside the recognition of qualifications, she said. The UK and other countries could still carry out “proportionate assessments” of professionals’ language knowledge.