A Former Walmart CEO Comes Down Under a Parachute

How a unique small aircraft (appears to have) saved those aboard

This morning, in Arkansas, a plane piloted by a former CEO of Walmart came down beneath a parachute on a main road in Fayetteville, Arkansas. You can see the plane just before touchdown, underneath its orange-and-white parachute, in the screen shot above.

Now, explanatory Q and A:

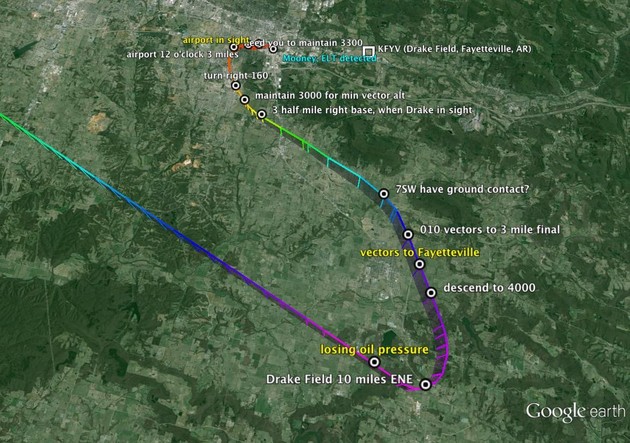

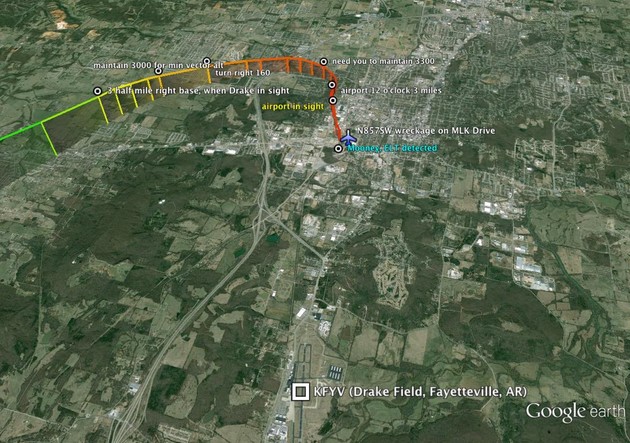

1) What happened here? William Simon, a former CEO of Walmart, took off this morning in a Cirrus SR-22 from an airport in Bentonville, Arkansas, Walmart’s headquarters city. The flight was headed southwest, toward Texas; not long after takeoff it developed engine troubles, and the pilot made a U-turn back to Drake Field in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Close to the ground, he decided he wasn’t going to make it all the way to the runway, and he pulled a parachute that allowed his plane and its passengers to descend safely onto a road.

If you’d like to see local news footage, you can check here. For recordings of the pilot’s discussion with air traffic controllers, you can listen to the MP3 here. (Start at time 14:20, and listen to the call to “Razorback,” the local controllers, from the plane “Cirrus eight five seven sierra whiskey.”) If you’d like to see the FlightAware track, go here.

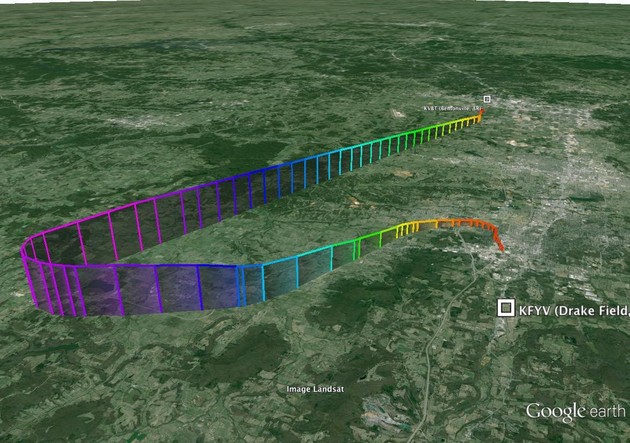

And if you’d like to see a schematic rendering of the entire flight, consult the illustration below. It’s from my friend Rick Beach, of the Cirrus Owners and Pilots Association, and it shows the plane’s elevation and path from takeoff in the upper part of the illustration to its landing in the lower right side.

2) What about this parachute? The built-in “ballistic parachute,” also known as the “parachute for the whole plane,” is a unique and distinctive feature of the Cirrus line of small aircraft. When the Cirrus SR-20 came onto the market 15 years ago, many grizzled aviators scoffed at it as a kind of training-wheels aircraft. Who would need a parachute? Real men would always be able to aviate themselves out of a bind!

Despite the scoffing, I bought one of the first SR-20s off the assembly line in 2000—and I wasn’t the only one to find the parachute a plus. Cirrus SR-20s and SR-22s are now the best-selling line of small aircraft in the world, which is a story I told in my book Free Flight and an Atlantic article “Freedom of the Skies.” The company’s factory is still in Duluth, Minnesota—but is now owned by the Chinese government, a story I told in China Airborne.

This is, as best I can reckon, the 55th of these Cirrus parachute saves since 2000 (of the 6000+ Cirri now flying), which have saved several times that many lives.

3) What was the pilot thinking? According to the air traffic control recordings and Rick Beach’s plot, the plane was at relatively high altitude for a flight outside the mountainous west (nearly 10,000 feet). When the engine developed trouble, the pilot maintained altitude for a while and then descended at the controller’s instructions. But as he was preparing for approach he decided he was losing altitude too fast to make it to the field.

In theory, you’re supposed to pull the parachute before you get within 1000 feet of the ground, for the parachute to work as planned and level out the plane for a three-point (as opposed to nose-down) touchdown. It appears as if the pilot pulled the parachute just soon enough.

4) Why not just glide the plane in? Everyone who has gone through pilot training has had to practice “no-power landings,” in which you cut the throttle and glide the plane to a landing—on a runway. It’s a different proposition to do so onto a pasture or field, which could look flat from 2000 feet up but prove to have fences or potholes when you’re nearing it at 80 mph, or on a main road like the one in Fayetteville, criss-crossed with wires and signs.

The force of sudden deceleration—damage from impact —goes up with the square of velocity. So a plane that is floating down under a parachute, with no forward velocity other than the wind’s, will have a lot less to deal with than one landing off-runway at around 80 miles an hour.

5) What have we learned here today? Small-aircraft flight is perilous. And the parachutes make it less so.