Tags

Berlin, Camp Essig, Dalum, Dalum Lingen, displaced people, Elms Lager, Hamburg, Irena Gierz, Lindenhof, Lingen, Ludwika Gierz, Nazi Germany, Neston, Ostarbeiter, Poland, Przedborów,, Westerstrasse, Westwell, Westwell’s Displaced People’s Camp Neston Wiltshire, world war II

There is no rest for the wicked…

There is no rest for the wicked…

I’m in the final stages of publishing “Ludwika” , my new historical novel about a Polish woman in Germany during World War 2.

I hope to present the book in London at the Kensington Christmas Book Fair in London, December 12th this year.

Cover designed again by the talented Daz Smith.

Blurb: It’s World War II and Ludwika Gierz, a young Polish woman, is forced to leave her family and go to Nazi Germany to work for an SS officer. There, she must walk a tightrope, learning to live as a second-class citizen in a world where one wrong word could spell disaster and every day could be her last. Based on real events, this is a story of hope amid despair, of love amid loss . . . ultimately, it’s one woman’s story of survival.

Review (from an Advance Review Copy) by Lorna Lee, author of “Never Turn Back” and “How Was I Supposed To Know”:

“This is the best kind of fiction—it’s based on the real life. Ludwika’s story highlights the magnitude of human suffering caused by WWII, transcending multiple generations and many nations.

WWII left no one unscarred, and Ludwika’s life illustrates this tragic fact. But she also reminds us how bright the human spirit can shine when darkness falls in that unrelenting way it does during wartime.

This book was a rollercoaster ride of action and emotion, skilfully told by Mr. Fischer, who brought something fresh and new to a topic about which thousands of stories have already been told.”

The book was inspired by a real story. ‘Ludwika’s family asked for my assistance in their ancestry research because one of my other books, “The Luck of the Weissensteiners”, touches upon similar issues of Displaced People in Germany after WW2. With strong support from my sister, who still lives in Germany, I spent several months gathering data and contacts. I was fascinated by the subject and re-read a lot of the books and sources and then decided to fictionalise Ludwika’s life.

People in extreme situations, like during WW2, had to make incredibly tough choices. There was no logic, guarantees or protection from the madness that raged at the time. So much bravery and hardship remains to be told and understood. By telling this story I hope to help fester humanitarian values.

Here is a little excerpt:

The mother still looked a little suspicious at Ludwika but as soon as the train had started she ran towards the toilet with Martin, the oldest of her boys. He had soiled himself by now, unable to wait and she had to clean him up and put some fresh clothes on. Ludwika smiled at the obedience to rules the young mother had demonstrated by not going to the bathroom, even though it was a child emergency. It occurred to her that from now on she would probably have to conform to the same bureaucracy and strictness.

By the time mother and son returned Ludwika had already made good friends with the remaining three, who were busy teaching her more German nursery rhymes. Martin, the young boy in new clothes, also joined in. The woman watched in awe as her children were completely taken in by Ludwika, almost oblivious to their mother. Once the inspector had seen and validated all of their tickets, the German woman took out a book and read. Ludwika froze when she saw that it was a book written by Adolf Hitler himself.

She heard her father’s encouragement in her head to keep going and not to worry about anything before there was a need for it. It was true, the woman would mean her no harm, not while Ludwika was taking care of the children.

After the singing had stopped the children told her about their grandparents’ big villa by the Alster in Hamburg and how they looked forward to eating ice cream at its shore. The mother had obviously decided to leave her to it and only occasionally spared a glance around the compartment, the rest of the time her head was turned towards the window and deep into her book. Undeterred, Ludwika was grateful for the children’s company and the happiness it brought her. The oldest boy, he looked about six, asked her to read them a story from their book and she happily obliged. It would be good practice for her. She found it very difficult, however, and the children didn’t seem to understand her renditions of a German folk tale.

The mother put her book down now and took the seat beside Ludwika.

“Don’t give up so easily,” she said. Ludwika couldn’t make out if the woman was scolding her or meant to encourage her. The tone was harsh but the face seemed benign.

Ludwika started a different fairy tale, and every time she mispronounced a word the woman would step in and correct her with surprising patience, while one by one the children fell asleep in their seats.

“You’re not bad at all for a foreigner,” the woman whispered. “Your German will get better over time. Don’t lose heart and keep going, then it will become easier and soon take care of itself.”

She looked her up and down.

“Where are you from, Ludwika?”

“Poland,” she replied, a little nervous.

“I know that, but which city?” the mother asked.

“Near Breslau,” Ludwika decided on.

“Are you Jewish?”

Ludwika jerked and shook her head vehemently.

“No,” she said quickly.

“Then I’ve got to thank you,” the mother replied, relieved. “My name is Irmingard. Irmingard Danner. You saved my life by giving me those two precious hours to read.” She looked towards the door and then she added in a low voice, so that nobody could hear: “My husband Erich has been hassling me to read that Hitler book for weeks now. My father-in-law works for the publishers and is a big shot in the party, too. He’s bound to ask me questions about it. I can’t make myself read the damn thing. Don’t you, too, find politics is so boring? As hard as I try, after ten minutes I can’t remember what I’ve read earlier. Today was the first time I could concentrate and I will be able to say at least a few intelligent things about it and do my husband proud.”

Wow – looking forward to reading it, Christoph – I think I’ll find part of my life in it too 🙂

Looks good to me – so far!

Thank you David 🙂

Thanks Ina. That would be really interesting to hear how your own life relates 🙂

We will exchange more on this, I’m sure 😀

That’s a great cover Christoph and reading the excerpt I was sorry it stopped, I was carried away reading. It’s very good. Good luck at the book fair! 😀

Thanks Annika ❤

Christoph… I’m so amazed by all the books you finish. Sincerely. This one sounds exciting. I think the cover speaks to the setting. (And I love old photos.)

Wishing you all the very best. Mega hugs

Thank you Teagan. Hugs! ❤

Looking forward to reading it Christoph. Difficult a story though it will be emotionally, I know it will be a great book with you at the writing helm. Good luck with it at the Kensington Fair. 🙂

Thank you xxx

Fabulous cover and the story sounds amazing. And it deserves to be told. Thanks.

Thanks Olga ❤

Reblogged this on Barrow Blogs: .

Thanks for thre re-blog ❤

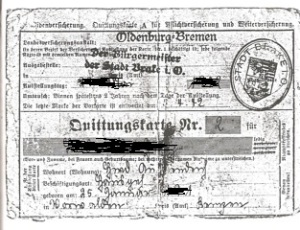

It sounds like an amazing story. The old photos are fascinating.

Thanks Mary 🙂

I will read this

Thank you 🙂

Sounds fascinating, my kind of read! Wow if only I could just read for a year I could get to all the books I want to read faster! 🙂

Me,too, Debby. We all need more hours in the day 🙂

Thank you ❤

Seems unanimous! 🙂

Reblogged this on MDellert-dot-Com and commented:

Looking forward to another great historical novel from Christoph Fischer!

Thank you so much for the re-blog 🙂

I was captivated by your exert and disappointed when it ended. Can’t wait to read the whole book. 🙂

Thank you. I hope to have it published by the 15th of December. I’d be happy to supply you with an Advance Copy of the book 🙂

Pingback: Excerpt #2 from “Ludwika: A Polish Woman’s Struggle To Survive In Nazi Germany” | writerchristophfischer

This story is about my step mums mother. She will be at the release today. Hope all goes well Christoph and i look forward to reading about my Grandmother that i never knew!

Thank you Stuart.

Your stepmom s visit was a lovely surprise.

The book even sold out 🙂

Hope you’ll enjoy it!

Pingback: Excerpt #3 from “LUDWIKA: A Polish Woman’s Struggle To Survive In Nazi Germany” | writerchristophfischer

Pingback: The wait is over: “Ludwika: A Polish Woman’s Struggle to Survive in Nazi Germany” has been released today! | writerchristophfischer

Pingback: My new release: Ludwika: A Polish Woman’s Struggle To Survive In Nazi Germany #excerpt three

Pingback: The Kensington Book Fair Experience | writerchristophfischer

Pingback: First Reviews for Ludwika: A Polish Woman’s Struggle To Survive In Nazi German

Looking forward to reading!

Thanks. I hope you’ll enjoy it when you get round to it 🙂

Pingback: A very Merry Author X-mas: Great first reviews for “Ludwika” and Readfreely honours for “Conditions” and “The Gamblers” | writerchristophfischer

Pingback: More great reviews for LUDWIKA and it’s unexpected appearance in a List of “Top Twenty Reads of 2015” | writerchristophfischer