Designing the technology of ‘Blade Runner 2049’

Territory Studios imagines the UI of a broken future.

This article contains spoilers for 'Blade Runner 2049'

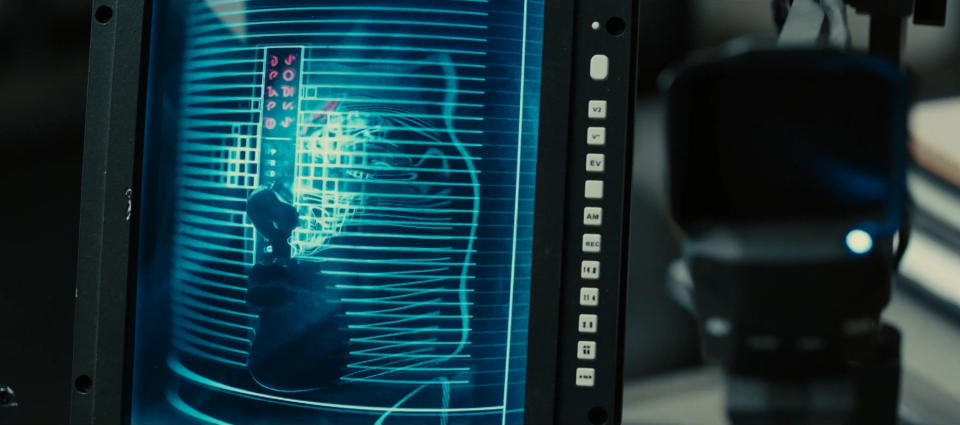

There's a scene in Blade Runner 2049 that takes place in a morgue. K, an android "replicant" played by Ryan Gosling, waits patiently while a member of the Los Angeles Police Department inspects a skeleton. The technician sits at a machine with a dial, twisting it back and forth to move an overhead camera. There are two screens, positioned vertically, that show the bony remains with a light turquoise tinge. Only parts of the image are in focus, however. The rest is fuzzy and indistinct, as if someone smudged the lens and never bothered to wipe it clean.

Before leaving the room, K asks if he can take a closer look. The blade runner -- someone whose task it is to hunt older replicants -- dances over the controls, hunting for a clue. As he zooms in, the screen changes in a circular motion, as if a series of lenses or projector slides are falling into place. Before long, K finds what he's looking for: A serial code, suggesting the skeleton was a replicant built by the now defunct Tyrell Corporation.

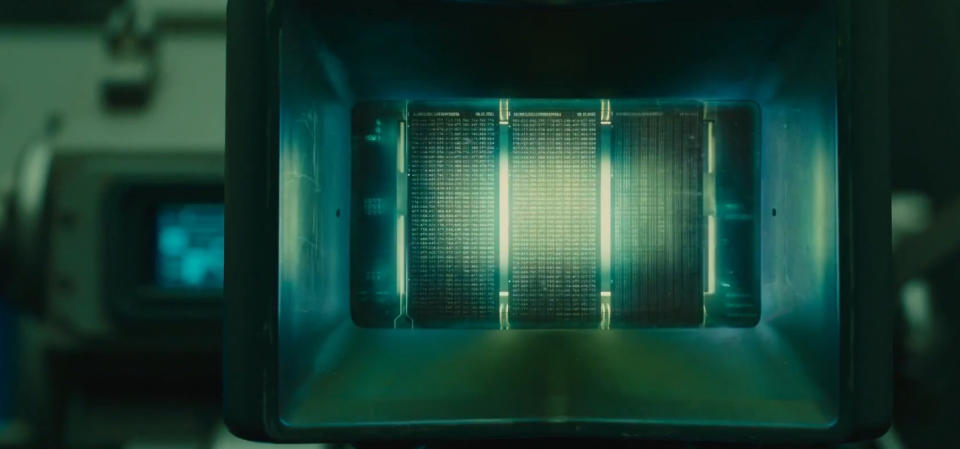

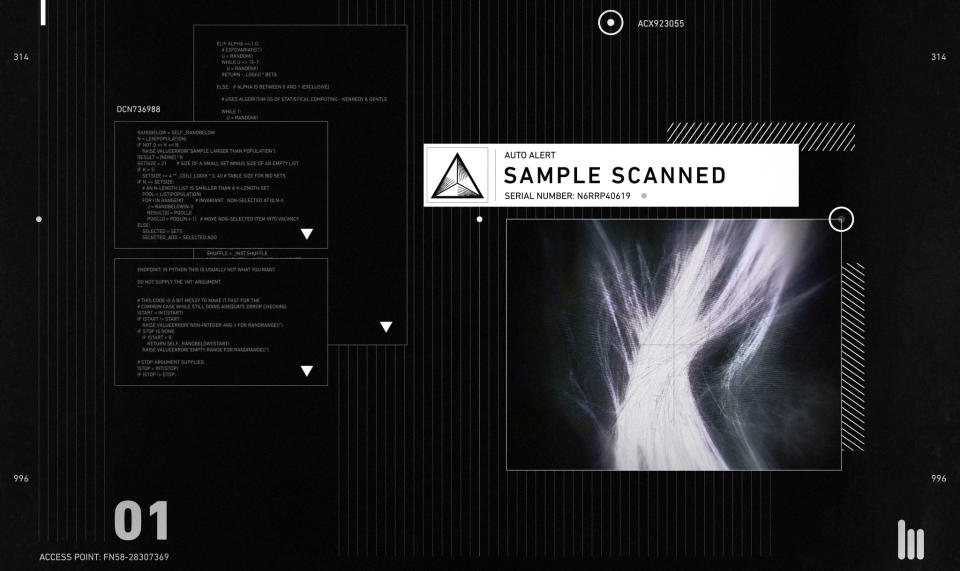

Throughout the movie, K visits a laboratory where artificial memories are made; an LAPD facility where replicant code, or DNA, is stored on vast pieces of ticker tape; and a vault, deep inside the headquarters of a private company, that stores the results of replicant detection 'Voight-Kampff' tests. In each scene, technology or machinery is used as a plot device to push the larger narrative forward. Almost all of these screens were crafted, at least in part, by a company called Territory Studios.

The London-based outfit is known for developing on-set graphics. These are screens, or visuals, that the actor can see and, depending on the scene, physically interact with during a shoot. They have the potential to raise an actor's performance while creating interesting shadows and reflections on camera. Each one also gives the director more freedom in the editing room. If you have a screen on set, you can shoot a scene from multiple angles and freely compare them during the edit. The alternative -- tailoring bespoke graphics for specific shots -- is a time-consuming process if the director suddenly decides to change perspective in a scene.

Territory has worked on a bevy of science-fiction films including Ex Machina, The Martian and Guardians of the Galaxy. One of its earliest and most prolific projects was Prometheus, the divisive Alien prequel directed by Ridley Scott in 2012. The team was hired to design the computers and screens inside the titular spaceship, which is ultimately overrun by an alien virus. You can see its work in various sets including the bridge, the medical area, and the ship's escape pods. In post, the company also handled the crew's hypersleep chambers, medical tablets and the HUD system that wraps around their POV helmet-cam feeds.

During the project, Territory worked with Paul Inglis, the film's senior art director, and Arthur Max, the production designer. Years later, David Sheldon-Hicks, co-founder and creative director at Territory, was talking on the phone with Max about Alien: Covenant. Instead, Max suggested that he reach out to Inglis about Blade Runner 2049. "So I dropped him an email," Sheldon-Hicks recalled, "and said, 'If you're on the project I think you're on, I will give you my right arm to put us on there.'" Inglis laughed and told him that unfortunately, Territory would have to go through a three-way bid for the contract.

It was a big moment. The original Blade Runner is considered by many to be the greatest sci-fi film ever released. Directed by Scott in 1982, it stars Harrison Ford, fresh off The Empire Strikes Back, as retired police officer Rick Deckard. He's forced to resume his role as a blade runner, tracking down a group of replicants who have fled to Earth from their lives off-world.

Blade Runner is a beautiful noir film filled with rain and neon lights. Based on the Philip K. Dick novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, it explores some heavy themes, such as what it means to be human, the importance of memories and how our obsession with technology could lead to societal and environmental decay. Critics had mixed reactions upon its release, but over time, the film's reputation has grown to the point where it's now considered a classic.

Blade Runner 2049 was, therefore, a huge creative gamble. Territory was awarded the contract in March 2016, before director Denis Villeneuve had released his award-winning sci-fi movie Arrival. The French Canadian was highly regarded, however, for his work on Prisoners, Enemy and Sicario. He had proven his ability to make powerful, thoughtful and visually stunning movies. Still, the stakes were enormous. So much time had passed since the original Blade Runner, and so many movies had riffed or expanded upon its ideas. To succeed, Blade Runner 2049 would need to be something special.

Peter Eszenyi was Territory's creative lead on Blade Runner 2049. He joined the company in 2011 to help Sheldon-Hicks with some idents for Virgin Atlantic's in-flight entertainment system. Eszenyi quickly moved on to movies, however, helping the team create computer screens, drone footage and satellite imagery for the 2012 political thriller Zero Dark Thirty. He's since worked on Guardians of the Galaxy, Marvel's Avengers: Age of Ultron and the live-action adaptation of Ghost in the Shell, to name just a few.

The company's work on Blade Runner 2049 started with a few cryptic calls. They were "terribly hard," Eszenyi recalled, because the film's producers were so secretive about the project. Territory was given a vague list of screens, or sets, that the studio thought they could help with. One line just read "K Spinner," for instance. But when Eszenyi asked for more information, the answer would always be the same: "No" or "We can't tell you." Despite the lack of information, Territory started working on mood boards, trusting that some eventual feedback would steer them in the right direction.

Inside the company, Eszenyi and Sheldon-Hicks were joined by creative director Andrew Popplestone, producer Genevieve McMahon and motion designer Ryan Rafferty-Phelan. (The team would scale up to 10 during the project, but these five were the core.) Together, they started looking for inspiration. The film's producers had given them one critical detail about the world: a massive, cataclysmic event had occurred since the previous film, wiping out most forms of modern technology. Blade Runner 2049 would still feature computers and screens, however. It was, therefore, Territory's job to help figure out what that meant and what everything would look like.

Inspiration came from all sorts of places. "It might be something you see in a shop window," Popplestone said. "You might be walking around here and see a piece of furniture that's made out of glass, or a sculpture, something like that." The team found a lot, unsurprisingly, online. They scoured Pinterest and other sites for interesting sculptures and photography. Slowly, they curated their images into themes, or ideas, that could be organized as Pinterest boards. The team would then get together and chat face-to-face, discussing their ideas before breaking off and pulling together more reference points.

"I vividly remember debating bacteria," Eszenyi said. "'Can they use certain types of bacteria to create green colors. Or blue ones?" They thought about jellyfish that often wash ashore and turn everything a startling shade of blue. Could they be harnessed somehow to create a primitive color display? How would that work? At one point they were imagining bacteria that could be genetically engineered to change color. They thought about computers that could excite them to trigger a color-switch, thereby altering the image. But then there was the screen. "Would this display be fast enough to be usable?" Eszenyi asked. "Or would it be a slow-changing kind of thing?"

A month later, four of the Territory team visited Budapest, Hungary, where most of Blade Runner 2049 was being shot. For Eszenyi, it was a surreal experience. He grew up in Hungary and remembers watching Blade Runner in secondary school. In particular, he recalled the sweeping, electronic score by Vangelis and his literature teacher gushing over the ending with replicant Roy Batty, played by Rutger Hauer.

With mood boards in hand, the Territory team were guided through studio security and into a meeting room with a table and a TV at the far end. It was completely empty, so the group started chatting amongst themselves. Then, suddenly, people started shuffling in. "We didn't realise that, one, we'd meet Denis, or that he'd be there," Popplestone recalled, "and, two, that it was going to be the entire visual effects team, and the producers as well." Ten or 12 people in total took a seat. Then they all turned and looked at Popplestone. "So I was like, 'Okay then!,'" he recalled. "Here's what we've got..."

But the team needn't have worried. Denis was warm but direct with his feedback. If something caught his eye, he would probe Territory about its meaning and how the group might develop the idea further. "It was always, 'I like *this* because of *this*,'" Eszenyi said. "What would you want to do with this? Where do you want to take it from here?" Some concepts he dismissed immediately, however. Eszenyi, for instance, liked an artist who had drawn illustrations for the Soviet-era space program. Beautiful illustrations of quiet, analog vessels from the 1970s and '80s. But they didn't match up with Villeneuve's vision.

The director disliked anything that felt too modern or sophisticated. If you could imagine it in a Marvel movie, for instance, he wasn't interested. But if it looked optical, like a microscope or a projector, he took notice. Glass, lenses and harsh lighting. Villeneuve also leaned toward nature; images that felt organic and abstract. "The whole point of the story is that we don't have digital-based technology," Popplestone said. "So he wanted something that was completely removed from that."

Before heading home, Territory visited the art department on set. The team was also given permission to step inside production designer Dennis Gassner's room, which was filled with concept art and storyboards. At last, the group felt like they had a good grasp of the movie and the world Villeneuve was trying to build.

Back in England, Territory refined its ideas. At its Farringdon office, the team experimented with physical props and filming techniques. They tried shooting through a projector to see how different lenses would warp the final image. The group took macro photographs of fruit, including a half-eaten grape that someone had left in the office. Eszenyi even looked at photogrammetry, a technique that uses multiple photographs and specialized algorithms to build 3D models. It's been used before to recreate real-life locations, such as Mount Everest, in VR and video games.

"It was almost like being back at university again," Popplestone said. The group operated like art students, experimenting with techniques that might produce abstract images or textures. A meeting room was eventually dedicated to the project, which the film's producers had code-named Triboro. "We just gave up on meetings," Sheldon-Hicks said. "The project took priority."

Eszenyi also became quite friendly with his local butcher. An assortment of "meat-based stuff," including pig's eyes started to gather in the office fridge, much to Sheldon-Hicks' displeasure. "I was like, 'Seriously, I'm getting takeaway for the next few weeks. I'm not going in there. It's horrible,'" he recalled with a chuckle.

Blade Runner 2049 was challenging because it required Territory to think about complete systems. They were envisioning not only screens, but the machines and parts that would made them work.

With this in mind, the team considered a range of alternate display technologies. They included e-ink screens, which use tiny microcapsules filled with positive and negatively charged particles, and microfiche sheets, an old analog format used by libraries and other archival institutions to preserve old paper documents. When the group was ready to present its new ideas, it was Inglis, rather than Villeneuve, that looked everything over and provided feedback. Inglis was working closely with the director and was, therefore, familiar with his ideas and preferences.

Slowly, Territory narrowed its focus. The team started shaping its abstract ideas into assets, or screens, that could be formally presented to Inglis and the rest of the film's producers. Around this time, the studio gained proper access to the art department and received a full breakdown of the work that needed to be completed. The team switched to Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator for its designs, applying animation in After Effects and professional 3D modelling software Cinema 4D.

"As soon as anything got too clean, or too fine, it was instantly going down the wrong direction," Popplestone said. The team created and curated libraries of textures and optical, line-based layers inspired by its real-world experiments. Distortion, warping and other artificial techniques were used to give the screens a grubby but beautiful look.

Territory was eventually given permission to read the script. The team had to fly to Hungary, however, to skim through the pages in an isolation chamber. "I had roughly half an hour to read the script," Eszenyi recalled. As such, he only had a rough idea of how the different sets and story sequences fitted together. Back in London, the team would constantly ask each other what they remembered from their brief time with the script. Thankfully, Inglis was always available to confirm anything they had forgotten.

"He was the arbiter of all information," Popplestone said.

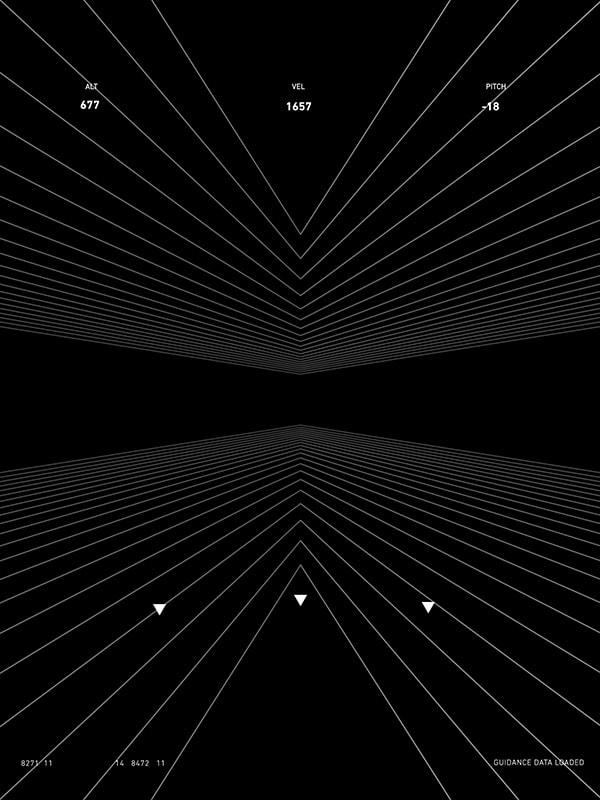

Near the end of the film, Deckard is handcuffed and bundled into a large spinner, which the team calls the Limo. It's owned by Wallace Corporation and is, therefore, a luxurious vehicle. Up front, barely in shot, you can see the pilot and a few screens with monochromatic designs. They're simple, sophisticated screens, conveying information with minimal dots and triangles.

That same design language can be seen inside the rest of the Wallace Corporation. It's a sparse but immediately recognisable look. Territory's goal was to build something that felt like Wallace's own, personalized operating system. So specialized, in fact, that Wallace wouldn't require the usual labels and iconography found on mass-market platforms like Windows and MacOS. It was designed for him, and is, therefore, supposed to be an extension of his tastes.

Wallace's employees, of course, aren't Wallace. So the implication is that everyone inside the company is using an operating system designed for someone else. "It speaks of corporate arrogance and confidence," Sheldon-Hicks said. "And a power that is beyond needing to worry about the masses."

The LAPD is a little different. K reports to Lieutenant Joshi, played by Robin Wright. The monitors in her office are chunky and the screens have a blue tinge to them. They're functional and better than what most of the public has access to, but a far cry from what Wallace Corporation uses. It's a reflection of how law enforcement and emergency services are run currently. The UK's National Health Service, for instance, still uses Windows XP. Police often have to wait to acquire new technology for their department.

Layering that context into screen designs can be tricky. The technology had to look outdated for 2049, but given the time period, also relatively futuristic. "It's old technology compared to Wallace," Popplestone explained, "but it's still advanced for us. So we had to make it look modern and more advanced than what we've got, yet still somehow slightly knackered and dilapidated."

Territory also had to be mindful of the original film and the off-screen events that Villeneuve had envisioned between 2019 and 2049. It was a relatively straightforward task; the sheer length of time and the cataclysmic event (partly explored in the Black Out 22 short by Shinichiro Watanabe) meant there was little the team had to reference or honor. That was by design. Villeneuve wanted a world "reset," so everyone on the project could freely explore new ideas. The film has Spinners, rain-soaked cities, and Deckard's iconic blaster, but otherwise there's little in the way of technological tissue.

"It was a completely clean slate," Eszenyi said.

Almost every screen Territory produced serves a specific purpose in the story. They help K uncover a new clue, or learn something interesting about another character. But each one also says something more about the world of Blade Runner 2049. What's common or unusual for people in different jobs and social classes. They hint at the state of the economy, the rate of innovation and how the development of artificial intelligence -- replicant and otherwise -- is affecting people's relationships and behavior with technology.

"It's a much more subtle, contextual narrative," Popplestone said.

Take the market. Partway through the movie K stands in the middle of a square, contemplating a series of photos. The film is focused on these images, but in the background you can see large, illuminated food adverts. They're square in shape, doubling as buttons that dispense orders like a giant gumball machine. Up above, animated banners advertise Coca-Cola and other food and drink products. It's one of the few times Territory designed graphics that didn't have a specific story function. They're still a point of interest, however, providing a rare look at how people live in this future version of Los Angeles.

Territory also had to think about how its screens would look in relation to the camera. Some were filmed up close, while others were only visible in the background. It was important, therefore, that designs were readable at different distances. To test this, the team constantly squashed and scaled up its graphics to see what they would look like on screen. "Does it have the detail to have a close lens on it? And can you go wide, and blur it out, and still read it?" Sheldon-Hicks said.

When a computer or machine is shown on film, it needs to be believable. Sometimes, a static display will do. But others require animation and multiple screens, or loops, to be chained together. Early in the movie, for instance, K steps into his personal Spinner. The screens lining the dashboard change as a call from Joshi comes in, and K scans the eyeball of a replicant he was hunting earlier. These are subtle, but necessary transitions to sell the idea that the vehicle is real.

Every shot was different, but generally Territory provided screens with an initial state, an action state, and then a looping state. Some screens had additional action states, if they were required to pull off a particular sequence. The different states were then triggered by actors or production staff on cue.

Territory could, in theory, design and code full-blown applications. But for a movie like Blade Runner, that would be a costly and time-consuming process. After all, a screen is largely redundant once the scene has been shot. There are also the practicalities of shooting a movie. An actor's focus is already split between the lights, the camera, the lines they need to remember, and the positioning of other cast members. If a screen or prop isn't simple, it could affect their focus and the overall quality of the performance.

Territory's graphics also have to serve the dialogue, changing with a certain rhythm or when particular lines are delivered. When Luv was looking for K's location, for instance, there needed to be a search tool, followed by a map that clearly showed his whereabouts. In the real world, you would probably get the following confirmation or prompt in Google Maps: "by The Cosmopolitan, did you mean...?" In a film, however, where pacing is critical, these intermediary screens are unnecessary and detract from the film's entertainment value.

"There are these push and pull factors of narrative versus reality," Sheldon-Hicks said. "You don't want to completely break away from reality. So we're always treading this line, or threading this needle on set in quite a tricky way."

Territory sent Rafferty-Phelan to Hungary to provide support while the movie was being filmed. There, he could answer questions and make last-minute changes required by Villeneuve or anyone else on set. These are normally small: sometimes the lighting is different than the team expected, or the director asks if some text can be adjusted. If the edits are minor, they can often be done on location by a member of the Territory team, avoiding difficult delays in shooting or expensive tweaks in post.

For Sheldon-Hicks, there's another reason to send his employees out on location. They're building a relationship with the director, who might want to work with them again in the future. It's also an opportunity for the company to collaborate and learn from some of the best creative talents in the industry. "It's like free training for me," he said. "I'm being paid to send my team out and see how Scott or Villeneuve tells a story. Of course I'm going to send them out." The more talented and experienced Territory becomes, the more likely it is to win contracts in the future.

Territory strives to deliver screens that can be shot with a camera on set. But there's always a chance something will need to be changed in post. Some films require extensive reshoots long after Territory has wrapped up its work on set. Other times, the film requires a particular look, or flourish, that simply isn't possible with current technology. Every project is different. On The Martian, for instance, Scott was able to shoot almost everything in camera. "The whole thing just went through in lens, done," Sheldon-Hicks recalls. Ex Machina, directed by Alex Garland, was the same.

Territory has been hired in the past to work on films, such as Ghost in the Shell, while they were in post-production. That means delivering concepts or assets that can be added to the movie after shooting has wrapped. With Blade Runner 2049, however, the company's work was finished once the cameras had stopped rolling. The team provided some resources so that other companies could tweak their work in post, but otherwise, its work was done.

Handing over control can be difficult, but it's all part of the filmmaking process. "There's just nothing you can do about it," Sheldon-Hicks said. "You know that they're all working to make the work better, and you don't want your graphics to look beautiful but be in a movie that sucks. So we all kind of accept that."

Eszenyi is "pretty sure" that parts of the morgue sequence were changed in post. It was a highly choreographed scene, with multiple props and screens, so the odds of a post-shot tweak were higher than other scenes in the movie. Still, it gave the actors real, visual cues to act off, and a basis for the graphical adjustment in post. So it's not like Territory's efforts were wasted. Even so, the team felt a mixture of emotions when they watched the first trailer in December last year. "It's like, yeah, that's my kid," Eszenyi explained, "but she's not two years old anymore, she's 18."

Blade Runner 2049 is a beautiful movie. The gloom of downtown Los Angeles and the harsh, radioactive wasteland of Las Vegas clash with the design decadence of Wallace Corp and the steely cold of K's apartment. The film's visual prowess can and should be attributed to cinematographer Roger Deakins and everyone who worked on the sets, costumes and visual effects. Territory's contributions can't be understated, however. By blurring the line between technological fantasy and reality, the team has made it easier to believe in a world filled bioengineered androids. Which is pretty cool for any fan of science fiction cinema.