Waymo, Google's self-driving car project, is planning to launch a driverless taxi service in the Phoenix area in the next three months. It won't be a pilot project or a publicity stunt, either. Waymo is planning to launch a public, commercial service—without anyone in the driver's seat.

And to date, Waymo's technology has gotten remarkably little oversight from government officials in either Phoenix or Washington, DC.

If a company wants to sell a new airplane or medical device, it must undergo an extensive process to prove to federal regulators that it's safe. Currently, there's no comparable requirement for self-driving cars. Federal and state laws allow Waymo to introduce fully self-driving cars onto public streets in Arizona without any formal approval process.

That's not an oversight. It represents a bipartisan consensus in Washington that strict regulation of self-driving cars would do more harm than good.

"A very difficult task"

"If you think about what would be required for some government body to examine the design of a self-driving vehicle and decide if it's safe, that's a very difficult task," says Ed Felten, a Princeton computer scientist who advised the Obama White House on technology issues.

Under both Barack Obama and Donald Trump, the federal government has taken a hands-off approach to driverless car regulation. Instead of enacting new safety regulations for self-driving cars, Felten says, federal policies have tried "to make sure that vehicle safety regulations don't inadvertently make it more difficult to roll out self-driving vehicles."

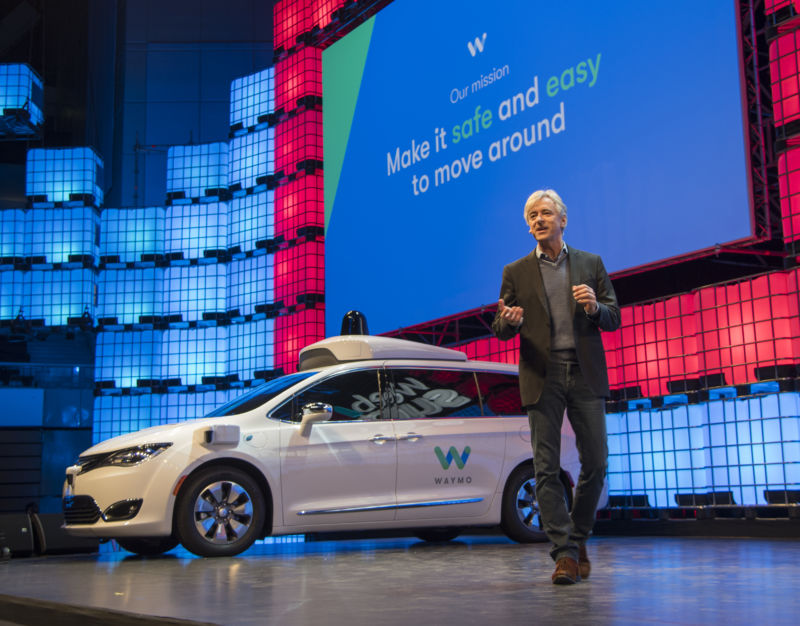

Self-driving cars do need to comply with an existing set of safety regulations called the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards. But that's not a big hurdle in practice. Waymo plans to address it by simply building its service using Chrysler Pacifica vans that are already FMVSS-compliant.

Meanwhile, Congress is considering legislation that would make it easier for companies to manufacture driverless vehicles that aren't fully FMVSS-compliant. This would allow GM to start making a car with no steering wheel as early as next year.

This hands-off regulatory approach drives some safety advocates crazy.

"I think it's stunning," says Cathy Chase, the head of the Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, about the deregulatory trend.

Mary "Missy" Cummings, an engineering professor at Duke, agrees. "I don't think there should be any driverless cars on the road," she tells Ars. "I think it's unconscionable that no one is stipulating that testing needs to be done before they're put on the road."

But so far these advocates' demands have fallen on deaf ears. Partly that's because federal regulators don't want to slow the introduction of a technology that could save a lot of lives in the long run. Partly it's because they believe that liability concerns give companies a strong enough incentive to behave responsibly. And partly it's because no one is sure how to regulate self-driving cars effectively.

When it comes to driverless cars, "there's no consensus on what it means to be safe or how we go about proving that," says Bryant Walker Smith, a legal scholar at the University of South Carolina.

Other industries face stricter regulation

To get an idea for what a more robust regulatory framework might look like, it's helpful to look at how the federal government regulates other complex, safety-critical technologies. Cummings did just that in a recent paper that compares the regulation of airplanes, medical devices, and cars.

An aircraft manufacturer is expected to meet with the Federal Aviation Administration while an airplane is still on the drawing board. Together, they draw up a plan that includes "a project timeline, checklists for moving on to the next phases, means of compliance, testing plans, and other project management information," Cummings writes. The FAA stays involved throughout the development process, verifying that the agreed-upon tests are passed before allowing a new airplane onto the market.

While the FAA is involved in aircraft design from the outset, the Food and Drug Administration typically waits until a medical device is ready for testing on human patients before getting involved.

Prior to clinical trials for a first-in-class device, a device maker must submit detailed technical information to the FDA, including a "device description, drawings, components, specifications, materials, principles of operation, analysis of potential failure modes, proposed uses, patient populations, instructions, warnings, training requirements, clinical evaluation criteria and testing endpoints, and summaries of bench or animal test data or prior clinical experience." The device maker then conducts the tests, submits the data to the FDA, and waits for FDA approval before bringing the product to market.

Waymo won't have to do anything remotely like this. The company has had informal discussions with government officials at the federal, state, and local levels. But there is no formal process requiring the company to submit information about its technology and test results to regulators in Phoenix or Washington. The law simply doesn't require Waymo to prove that its driverless technology is safe before putting cars on the road.

The rigorous processes for approving airplanes and medical devices come at a high cost. Cummings says that it can take as much as eight years to bring a new airplane to market. A survey of medical device companies found that it took an average of four-and-a-half years for the FDA to sign off on a new medical device (the FDA's process is shorter than the FAA's partly because the agency doesn't get involved until after the product has been developed). And it cost $94 million, on average, to bring a new medical device to market.

Self-driving car advocates argue that slowing down the development of self-driving cars could ultimately cost more lives than it saves. In 2016, more than 37,000 people died from highway crashes, with many being caused by human error, so self-driving cars have the potential to prevent thousands of highway deaths in the coming years.

reader comments

188