It may have been a summer filled with high-profile breakups, but for educators, perhaps the most shocking split came this September—not in Hollywood, but Silicon Valley—when Intel and the Science Talent Search (STS) announced they were ending their 17-year relationship. Like a jilted lover, the Society for Science & the Public announced it would be seeking new sponsorship for its high-school competition, which has effectively served as the country’s premiere science fair since its inception in 1942. Fans of the competition reacted accordingly, taking to Twitter to share stories of the one-time romance, bemoan the breakup, and offer up a collective cry of “Why?!”

“I’m shocked,” said Michael Blueglass, president of the Westchester Science and Engineering Fair, one of the feeders for the national competition. “They sponsor the two biggest STEM-education fairs in the world,” he continued, referring to the STS and Intel’s International Science and Engineering Fair. Intel will continue to sponsor ISEF through 2019; the STS sponsorship will end in 2017. “To give that up doesn’t make sense.”

The last time STS sought a new sponsor was in 1997, when Westinghouse, fading from existence as a manufacturing company, dropped its involvement. That split surprised no one; the company had been slowly declining for a decade before becoming subsumed by CBS. According to Michelle Glidden, who worked in the Science & the Public press office on the day Westinghouse’s departure was announced, a number of companies quickly offered up sponsorship deals to fill the void. But the financial problems that plagued Westinghouse don’t seem to be at play for Intel: The company’s gross revenue was $55.9 billion last year, and according to a New York Times report on the dropped sponsorship, the science contest costs about $6 million a year to run.

Both parties have remained quiet on the cause of the split. STS simply sent out its press release. Intel offered no explanation in the Times story, nor did it respond to a request for comment. Did STS want someone younger and sexier? Or maybe it was Intel who called it quits, no longer finding value in the long-running fair. The Times reports that there hasn’t been a drop in the number of projects coming to STS. But despite the increasing proliferation of prominent science fairs—the prestigious competitions hosted by Google and the White House are among those to have recently entered the fray—local school and county fairs have been on the wane. The number of schools participating in the Los Angeles County Science Fair, for example, has dropped from 244 to 185 in the last decade. At one regional fair in Virginia, the number of entrants declined by more than half over a recent eight year period; the head of the competition blamed the emphasis on testing to comply with No Child Left Behind standards.

Earlier this year I wrote about some of the problems afflicting science fairs: Many schools struggle to balance science-fair curricula with test prep, or ask students to do their projects on the side with little to no guidance. To excel at STS, students typically need access to a high-tech lab and an actual scientist who can help guide their research, which means that science-fair aspirants who don’t live near a big research laboratory or university can be effectively shut out. Not surprisingly, many of the national fairs’ winners have been students from schools with dedicated science-fair classes that are located near research facilities.

And the fairs often come under criticism from both teachers and scientists for their strict adherence to the scientific method, which some have argued doesn’t align with the way science actually works. So it’s possible that in a freewheeling world—one where there are fellowships encouraging students to quit college and start a company, executives flock to hackathons to prove they too can dream big, and college dropouts run billion-dollar companies—Intel sees the STS as too passé, the kind of thing one’s grandparents might have done (possibly arriving in a Buick and wearing a pocket protector). Or, to put it another way, there are other competitions out there that don’t care one iota about the scientific method and poster board, and that are more accessible to the general public. To showcase a project at a competition like Maker Faire, for example, you don’t even need to be in school.

“My sense is that Maker is much less about rules,” said Glidden, who is now the Society for Science & the Public’s director of science education programs. “It’s very much about independent gadgeteering and using your hands and inventing.” And while the STS certainly sees a lot of invention, she said, it’s “with a defined sense that I’m not sure Maker follows.”

In fact, Maker Faire could be a big part of Intel’s decision to drop its support of the STS in the first place. The tech company will continue to fund not only Maker Faire but also MakerCon, an event that focuses on bringing the products that come out of the competition to market. Maker Faire is perhaps everything that traditional science competitions are not. Whereas science fairs’ roots hearken back to a mix of agricultural displays on corn and Cold War-fueled hysteria, Maker Faire emerged in 2006 in the Bay Area and feels more like Burning Man meets Radio Shack. Maker also does away with the lab-access issue that many science-fair hopefuls run up against by favoring projects that can be done with readily available technologies like Raspberry Pi and Arduino. Recent winners at Maker have included 3D printed robots, a Raspberry Pi teletype that wirelessly connects an iPad to a 60s-era teletype machine, and an Arduino-compatible processor.

Conversely, the grand prize winners at the STS focus less on technology and more on traditional scientific arenas. According to an Intel employee who previously judged the International Science and Engineering Fair, Intel sees the contest as a way to identify future Intel employees, so the lack of focus on technology could make the contest less attractive to the company. This year’s nine winners and finalists at the STS showcased research primarily in cancer, mathematics, physics, and biology—all noble scientific efforts, but not research that is likely to generate employment offers from a semiconductor chip manufacturer.

Maker Faire participants, on the other hand, can purchase products directly from Intel and then exhibit the fruits of their labor at Maker events. And in some cases, those products turn into technologies or businesses that get bought by—you guessed it—Intel.

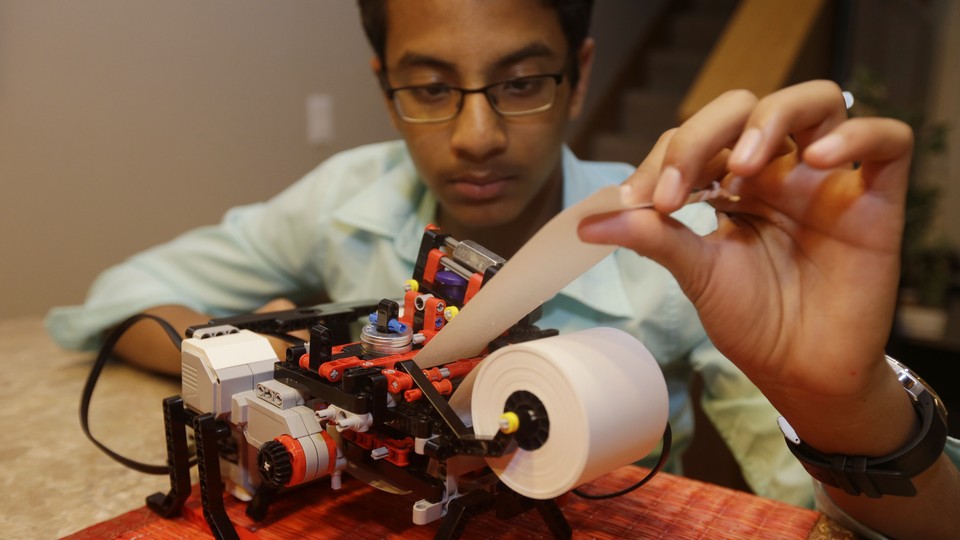

Student-inventor Shubham Banerjee offers an excellent case in point. Last year, Shubham built a low-cost Braille printer using parts from Lego Mindstorms—an advanced Lego kit that contain programmable elements—for his seventh-grade science fair project. But instead of taking the printer on to STS, he brought it to Maker Faire, where it won an Editor’s Choice Ribbon. Shortly after, Intel announced that it was investing in the product; the next version of the printer will include an Intel Edison chip, and won’t be made out of Legos. So it’s likely that competitions like Maker offer more of a direct funnel for both projects and potential employees than does STS.

But there could be another reason for the drop in sponsorship: diversity. Intel’s CEO, Brian Krzanich, announced in January that Intel would be investing $300 million in “hiring and retention programs, growing the tech pipeline, increasing investments in diverse entrepreneurs, and supporting women in gaming.” One (highly partisan) site speculated that the money previously allocated for the science fair will now be going to Intel’s Diversity in Technology initiative. But another read is that the winners at STS simply aren’t diverse enough to fit with Intel’s new direction. Over the last year, eight schools from the greater New York City area have dominated the winners list as the STS. Maker Faire doesn’t provide a comprehensive listing of its blue ribbon and editor’s choice winners, so it’s unclear whether that competition caters to a more diverse crowd. But with a grassroots feel, easy access to technology, and Maker Faires all across the country, it’s likely that winners are more diverse in geographic origin if not in gender.

So does this mean that the Science Talent Search is on it’s way out? Glidden doesn’t think so—she pointed out that many kids enter both STS and Maker, and said that at least one has claimed top honors in both. And while the projects at STS may not be the future for Intel, Glidden says she’s seen topics evolve to “reflect the world that’s around them.” Drones and alternative fuels, for example, are two increasingly popular areas of research. Regardless of the area of investigation, STS “has always been about the potential of students to be a future scientist,” she says.

But maybe that’s the problem. Future scientists are a worthy investment, but judging by Shubham Banerjee’s story, Intel may be more interested in projects that feel a little more futuristic, fun, and media-focused. In addition to the Maker Faire sponsorship, Intel had a heavy presence at the most recent New York Fashion Week with clothing that featured wearable technology, and the company will also be involved in a reality show on TBS featuring a competition to build projects around the Intel Curie system. It’s unclear whether Maker and reality television will lead to a more democratic and diverse landscape of winners than STS. But if nothing else, at least they’ll be moving beyond poster board and rigid adherence to the scientific method. And for some other company looking to boost its image in the STEM education community, there’s now a very nice sponsorship opportunity available.

“It was very shortsighted of Intel,” said Blueglass, of the Westchester Science and Engineering Fair. “Whoever comes in now and takes over and runs this will look like a hero.”