This will be remembered as a good year for cereal yields across most but not all of the country. Many were amazed at the performance of crops that looked both average and good – often exceeding expectations considerably. But not all growers benefited from the good year.

In this article, I give my take on what may have happened in 2015. Perhaps nobody will ever fully understand exactly what occurred and it certainly can only be addressed with the benefit of hindsight. That said, many recent years with slow cold springs generated the potential to deliver good crops.

Let’s take a quick walk back through the crop season. The majority of winter crops were sown in good conditions, established well and had full canopies.

The mild autumn, combined with early planting, resulted in pressure from BYDV in some regions and this resulted in yield penalties for some growers.

Spring crop planting conditions were slightly more variable and planting was late compared with other years. But establishment was good in the majority of crops.

The following few weeks of spring were less than ideal though and the combination of cold and wet slowed growth and canopy formation, leaving crops looking poor and miserable with some headland suffering.

Feeding max growth

We always associate good yields in spring crops, and barley in particular, with continuous and rapid growth post-establishment. This still holds as an objective.

In springtime, we hope for good growth conditions to help build canopy and yield potential in all crops. It takes nice weather and warm temperatures to do this. But rapid growth requires a lot of feeding and a big supply of nutrients and if any one of these – major or trace – is in limited supply then growth will be curtailed. And early growth builds yield potential.

However, in my opinion it is not as simple as growth being curtailed. When plant growth is driven by temperature then it must grow. If it cannot get enough feed from the soil then it will scavenge on itself to fuel this growth.

It is at these precious times of rapid growth that yield potential is being set and if a rapidly growing crop is not adequately nourished then it must effectively decrease its potential yield capacity in order to fuel the growth.

Plant growth is most rapid during the early stem extension growth stages. During this time, if it cannot continue to build its potential yield it is effectively decreasing its potential. There can be no neutral positions during rapid growth. A plant is either increasing or decreasing its yield potential. It is for this reason that early season nutrition is so important.

This is one of the main reasons behind the benefit of fertiliser placement in spring barley in particular. This may equally apply to winter barley as the barley crop is probably most restricted in the generation of its potential yield by the number of grain sites it can establish per square metre.

Now let’s get back to the spring of 2015. Cold with occasional excess moisture is a brief summary, ie not very good growth conditions. However, when the plant is growing more slowly, its daily or hourly requirement for nutrition is also reduced. So was the slow growth, which ultimately delayed harvest, more of a benefit than a constraint?

I believe the answer is yes. And it is especially yes on more worn land where mineralisation is limited, soil structure may be less then desirable and fertility may be below par. On this type of land the slow growth probably helped plants to remain in the net yield generation phase because they were less likely to hit nutrition constraints when growth was slow.

This theory may generally apply less to wheat and oats but it still applies. While these crops have the capacity to better compensate for lower ear counts or smaller spikelet number per ear, potential yield is still being increased for as long as plants do not meet with nutritional constraints.

Importance of

healthy soil

Being able to feed a rapidly growing plant is also the principle behind the “pet field” and the provision of a fertile, well-structured soil. A healthy soil with active organic matter mineralisation, high fertility and increasing humus level is the best way to ensure that a growing plant can be provided with all of the nutritional factors it requires.

It is for this reason that good soil health and nutrition is seen as key to the more consistent delivery of yield levels that are closer to the genetic potential of the varieties we are growing.

There will always be a year effect but we need this to fluctuate around 5t of wheat per acre, rather than 4t, and 3.6t of spring barley per acre, rather than 2.8t/ac.

This advice is slow to be adopted because it is not an instant bag or bottle cure. And it generally requires additional work in an environment where most growers are busy chasing scale which provides little in the way of margin or profit.

Poor yields in the south

So what about the poor yields in 2015? Well if you were in the western or northern regions you would not have really expected good yields. While you would hope for big yields, the large volumes of almost continuous rainfall during the year made this very unlikely in most of these regions.

But for the majority of growers in the east and south, the high yield potential generated by the slow early growth was delivered.

However, even in the early harvest it became obvious that the big yield levels were not happening in some areas along the south coast. These crops looked as good as crops elsewhere but they just did not produce the big tonnage.

In some instances, yields were still quite good but quality suffered. This left a big issue for malting barley in parts of the south where lack of specific weight caused a lot of spring barley to be rejected for malting.

There were a number of peculiar aspects to this problem. When you cut a yield of 2.8t/ac to 3.3t/ac of spring barley you have a realistic expectation that these crops will also have good quality. But for many crops across south and east Cork, this was not the case. Growers there ask why this happened but that answer is not so easy. One would expect that it had something to do with some element of local weather conditions.

Information made available to me by Met Éireann suggested no massive climate difference between this southern region and most other areas where yields were generally higher.

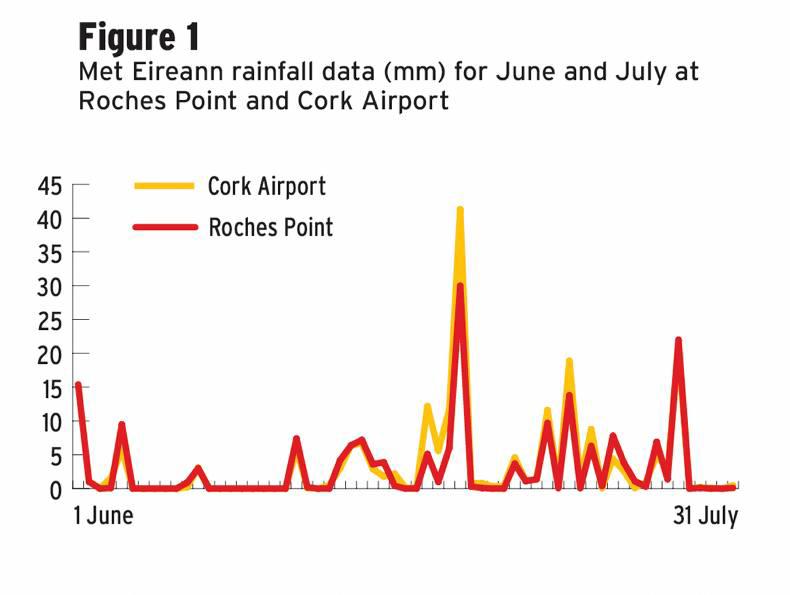

Temperature and sunshine levels showed no major difference at Roche’s Point and Cork Airport but rainfall was much higher in early July, as indicated in Figure 1. The other slight anomaly was that temperatures were considerably lower than normal in the days preceding this July rainfall peak.

The consequences of this early July rainfall are probably best seen in the rainfall graph in Figure 2. In the week spanning 30 June to 6 July, southern areas received over 250% of normal rainfall for that week, with some areas up to 400% of normal.

Given the late crop development in 2015, the waterlogged conditions (combined with the cold) could have impacted on the late grain fill in late winter barley crops and on grain fill in spring barley and winter wheat crops.

Yield potential

If crops in the area benefited from the same high yield potential generated by the cool spring, it seems to me that high grain number was the most likely reason for this high potential. And where crops did not look particularly thick, it was either late tillers or more grains per ear that enabled this to occur.

This makes a degree of sense for these southern crops. Where one ended up with a big grain count per unit area, it is likely that all of these grains might be less well filled if growth was subsequently limited during grain fill. This could go some of the way to explaining how one could get good yields but still suffer on quality.

Where these grains had been filled fully, quality would have been much better and grain yield might have hit the heights of crops further north.

By all accounts, winter wheat fared that bit better in these circumstances because it has a greater capacity to recover. However, reports of a level of poorly filled grains in otherwise very good looking samples of wheat would support a similar explanation.

In the wheat plant, rather than filling all grains less well, the natural dominance in the head could effectively abandon a number of grains per ear during grain fill to support adequate fill in the majority of others. This could result in a generally good-looking sample with some poorly filled grains present but yield will still have suffered to some degree.

This explanation can only partly explain what happened specific crops in this region as there were some very good crops too. Could the difference be as simple as the location and intensity of local showers?

This has certainly been an issue in other parts of the country in recent years.

The high percentage rainfall in these southern regions (Figure 2) is all the more significant in that the base rainfall levels are much higher for there than for most other cropped areas up along the east of the country in particular.

Soil is key to potential

There is little that one can do to mitigate weather events like these. However, as explained earlier in this article, a healthy well-structured soil will help offset some of the consequences.

Good structure helps a soil to drain more freely and so reduces the risk of waterlogging in wet periods. It also enables roots to explore a bigger volume of soil to help feed the crop at critical demand times.

Healthy productive soils need to be fed with organic matter. This helps restore good physical structure with the assistance of earthworms. This process also provides humus which further helps nutrient availability at peak demand times and provides a critical store of moisture for light free-draining soils in dry years.

Having soil in good health and fertility is the only way that one can hope to repeat the high yield levels experienced in 2015.

This is not an instant process so the sooner you act to improve your worn soils the quicker you can begin to grow crops that make economic sense.

Yield potential in 2015 was probably helped by the slow spring growth which decreased the daily demand for nutrition.Most areas generated high yield potential but adverse conditions during grain fill may have prevented the realisation of this potential, especially in parts of the south, and this may also have contributed to low quality.Healthy and well-structured soils are key to enabling the realisation of our high genetic yield potential.

This will be remembered as a good year for cereal yields across most but not all of the country. Many were amazed at the performance of crops that looked both average and good – often exceeding expectations considerably. But not all growers benefited from the good year.

In this article, I give my take on what may have happened in 2015. Perhaps nobody will ever fully understand exactly what occurred and it certainly can only be addressed with the benefit of hindsight. That said, many recent years with slow cold springs generated the potential to deliver good crops.

Let’s take a quick walk back through the crop season. The majority of winter crops were sown in good conditions, established well and had full canopies.

The mild autumn, combined with early planting, resulted in pressure from BYDV in some regions and this resulted in yield penalties for some growers.

Spring crop planting conditions were slightly more variable and planting was late compared with other years. But establishment was good in the majority of crops.

The following few weeks of spring were less than ideal though and the combination of cold and wet slowed growth and canopy formation, leaving crops looking poor and miserable with some headland suffering.

Feeding max growth

We always associate good yields in spring crops, and barley in particular, with continuous and rapid growth post-establishment. This still holds as an objective.

In springtime, we hope for good growth conditions to help build canopy and yield potential in all crops. It takes nice weather and warm temperatures to do this. But rapid growth requires a lot of feeding and a big supply of nutrients and if any one of these – major or trace – is in limited supply then growth will be curtailed. And early growth builds yield potential.

However, in my opinion it is not as simple as growth being curtailed. When plant growth is driven by temperature then it must grow. If it cannot get enough feed from the soil then it will scavenge on itself to fuel this growth.

It is at these precious times of rapid growth that yield potential is being set and if a rapidly growing crop is not adequately nourished then it must effectively decrease its potential yield capacity in order to fuel the growth.

Plant growth is most rapid during the early stem extension growth stages. During this time, if it cannot continue to build its potential yield it is effectively decreasing its potential. There can be no neutral positions during rapid growth. A plant is either increasing or decreasing its yield potential. It is for this reason that early season nutrition is so important.

This is one of the main reasons behind the benefit of fertiliser placement in spring barley in particular. This may equally apply to winter barley as the barley crop is probably most restricted in the generation of its potential yield by the number of grain sites it can establish per square metre.

Now let’s get back to the spring of 2015. Cold with occasional excess moisture is a brief summary, ie not very good growth conditions. However, when the plant is growing more slowly, its daily or hourly requirement for nutrition is also reduced. So was the slow growth, which ultimately delayed harvest, more of a benefit than a constraint?

I believe the answer is yes. And it is especially yes on more worn land where mineralisation is limited, soil structure may be less then desirable and fertility may be below par. On this type of land the slow growth probably helped plants to remain in the net yield generation phase because they were less likely to hit nutrition constraints when growth was slow.

This theory may generally apply less to wheat and oats but it still applies. While these crops have the capacity to better compensate for lower ear counts or smaller spikelet number per ear, potential yield is still being increased for as long as plants do not meet with nutritional constraints.

Importance of

healthy soil

Being able to feed a rapidly growing plant is also the principle behind the “pet field” and the provision of a fertile, well-structured soil. A healthy soil with active organic matter mineralisation, high fertility and increasing humus level is the best way to ensure that a growing plant can be provided with all of the nutritional factors it requires.

It is for this reason that good soil health and nutrition is seen as key to the more consistent delivery of yield levels that are closer to the genetic potential of the varieties we are growing.

There will always be a year effect but we need this to fluctuate around 5t of wheat per acre, rather than 4t, and 3.6t of spring barley per acre, rather than 2.8t/ac.

This advice is slow to be adopted because it is not an instant bag or bottle cure. And it generally requires additional work in an environment where most growers are busy chasing scale which provides little in the way of margin or profit.

Poor yields in the south

So what about the poor yields in 2015? Well if you were in the western or northern regions you would not have really expected good yields. While you would hope for big yields, the large volumes of almost continuous rainfall during the year made this very unlikely in most of these regions.

But for the majority of growers in the east and south, the high yield potential generated by the slow early growth was delivered.

However, even in the early harvest it became obvious that the big yield levels were not happening in some areas along the south coast. These crops looked as good as crops elsewhere but they just did not produce the big tonnage.

In some instances, yields were still quite good but quality suffered. This left a big issue for malting barley in parts of the south where lack of specific weight caused a lot of spring barley to be rejected for malting.

There were a number of peculiar aspects to this problem. When you cut a yield of 2.8t/ac to 3.3t/ac of spring barley you have a realistic expectation that these crops will also have good quality. But for many crops across south and east Cork, this was not the case. Growers there ask why this happened but that answer is not so easy. One would expect that it had something to do with some element of local weather conditions.

Information made available to me by Met Éireann suggested no massive climate difference between this southern region and most other areas where yields were generally higher.

Temperature and sunshine levels showed no major difference at Roche’s Point and Cork Airport but rainfall was much higher in early July, as indicated in Figure 1. The other slight anomaly was that temperatures were considerably lower than normal in the days preceding this July rainfall peak.

The consequences of this early July rainfall are probably best seen in the rainfall graph in Figure 2. In the week spanning 30 June to 6 July, southern areas received over 250% of normal rainfall for that week, with some areas up to 400% of normal.

Given the late crop development in 2015, the waterlogged conditions (combined with the cold) could have impacted on the late grain fill in late winter barley crops and on grain fill in spring barley and winter wheat crops.

Yield potential

If crops in the area benefited from the same high yield potential generated by the cool spring, it seems to me that high grain number was the most likely reason for this high potential. And where crops did not look particularly thick, it was either late tillers or more grains per ear that enabled this to occur.

This makes a degree of sense for these southern crops. Where one ended up with a big grain count per unit area, it is likely that all of these grains might be less well filled if growth was subsequently limited during grain fill. This could go some of the way to explaining how one could get good yields but still suffer on quality.

Where these grains had been filled fully, quality would have been much better and grain yield might have hit the heights of crops further north.

By all accounts, winter wheat fared that bit better in these circumstances because it has a greater capacity to recover. However, reports of a level of poorly filled grains in otherwise very good looking samples of wheat would support a similar explanation.

In the wheat plant, rather than filling all grains less well, the natural dominance in the head could effectively abandon a number of grains per ear during grain fill to support adequate fill in the majority of others. This could result in a generally good-looking sample with some poorly filled grains present but yield will still have suffered to some degree.

This explanation can only partly explain what happened specific crops in this region as there were some very good crops too. Could the difference be as simple as the location and intensity of local showers?

This has certainly been an issue in other parts of the country in recent years.

The high percentage rainfall in these southern regions (Figure 2) is all the more significant in that the base rainfall levels are much higher for there than for most other cropped areas up along the east of the country in particular.

Soil is key to potential

There is little that one can do to mitigate weather events like these. However, as explained earlier in this article, a healthy well-structured soil will help offset some of the consequences.

Good structure helps a soil to drain more freely and so reduces the risk of waterlogging in wet periods. It also enables roots to explore a bigger volume of soil to help feed the crop at critical demand times.

Healthy productive soils need to be fed with organic matter. This helps restore good physical structure with the assistance of earthworms. This process also provides humus which further helps nutrient availability at peak demand times and provides a critical store of moisture for light free-draining soils in dry years.

Having soil in good health and fertility is the only way that one can hope to repeat the high yield levels experienced in 2015.

This is not an instant process so the sooner you act to improve your worn soils the quicker you can begin to grow crops that make economic sense.

Yield potential in 2015 was probably helped by the slow spring growth which decreased the daily demand for nutrition.Most areas generated high yield potential but adverse conditions during grain fill may have prevented the realisation of this potential, especially in parts of the south, and this may also have contributed to low quality.Healthy and well-structured soils are key to enabling the realisation of our high genetic yield potential.

This is a subscriber-only article

This is a subscriber-only article

SHARING OPTIONS: