Just Another Shitty Day

The pungent adventures of a fecal sludge scientist

“It’s just another shitty day in Africa.”

That’s the local humblebrag for a perfect July day in Durban, South Africa: sunny skies, cool air — the perfect day for emptying a pit latrine. Here I am, thousands of miles away from my office at North Carolina State University, getting ready to open up a Ventilated Improved Pit Latrine (VIP) to sample fecal sludge material.

The non-technical description: I’m about to dig a hole in the ground and look at human shit.

It’s both gross and fascinating, this job. You move the concrete slab at the back of the toilet house (the “superstructure”) to access the pit — a 1.5-cubic-meter box made of concrete blocks — and behold the glory of human waste: fecal material, lots of it, and trash, including newspaper, plastic bags, plastic bottles, rags, shirts, shoes — anything and everything deemed unworthy of keeping. The newspaper and toilet paper are to be expected. In informal settlements, like this one in Bester’s Camp in eThekwini municipality, the communities are “wipers.” But there are also bottles, jeans, feminine hygiene products — household waste that would normally go into the trash system, if one existed here. But it doesn’t.

In many ways, this settlement is better than most. The eThekwini municipality provides water (the first 9,000 liters per month are free) and empties the VIP for free every five years. South Africa is unique in this aspect: access to water and sanitation are explicitly considered part of the government’s duty. In many parts of the world, there are no toilets or water.

An astounding 2.5 billion people in the world — mostly in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia — have no access to adequate sanitation, and 1 billion practice open defecation.

Yup, that’s the technical term for shitting in public spaces — behind bushes, in fields, along railroad tracks.

Even in cities where there happen to be toilets, an analysis of where the fecal material goes — a “shit-flow diagram” — shows that only a tiny fraction is treated before being released into the environment. In Dhaka, Bangladesh, for example, only 2 percent of fecal material is treated to an acceptable level. The majority of shit gets dumped illegally into soil and water or flows into rivers without adequate treatment. In many cities in the developing world, people are surrounded by shit, often unbeknownst to them.

The resulting toll on human health is astounding. International agencies estimate that due to lack of sanitation, there are more than 600,000 child deaths every year from diarrheal infections and related diseases and high rates of infant mortality and stunted growth in children. Poor sanitation has devastating consequences for the environment: rivers bubbling with methane gas, devoid of all life; soils with high fecal loadings; groundwater contaminated with fecal bacteria.

It also takes an economic toll. The WHO estimates that health care costs, lost worker productivity, days lost in school, and missed opportunities in growth of new industries can account for 1.5 percent of global GDP. It’s clear that we must confront the problem now.

My personal confrontation with shit at the VIP is under way. We have PPE (personal protective equipment) consisting of face masks, safety suits, and gloves, but the smell and the sight are overwhelming. I am determined not to be the first researcher to heave while in the field, and for the moment my constitution is holding up.

My goals are to collect samples at different depths from the front and the back of the VIP; to confirm that different degradation processes are occurring in fresh versus aged fecal material; and to better understand degradation and filling-up rates in pits. Some pits appear to fill up faster than expected, while there are reports of magical pits that never fill up. Humans have buried waste for millennia, but we have little information on the detailed microbial decomposition that happens.

Bending over the access hole, I thank heavens that we hired a professional pit-emptying crew to assist us. There are several such crews in the municipality, with access to training, inoculations, and PPE. The ones we’re working with are lucky. In many countries in Africa and Asia, manual pit emptiers and scavengers are ostracized and looked down upon, forced to work at night, unseen.

In India, Dalit women are condemned to clean toilets and collect the fecal material, which they put into woven baskets that they carry on their heads. The children of Dalits learn to do this at an early age. In many African countries, such as Ethiopia, men are contracted to empty pit latrines in the middle of the night. They drink alcohol heavily, perhaps to muster the fortitude to do the job, perhaps to forget that this is human shit they’re handling.

This is about as close you can get to human fecal matter: you’re waist-deep into it, using a bucket to bail out and empty pits, hand over hand.

The workers we hired are adequately paid and well trained. One of them shovels up the material for our inspection, and my colleague Tina Velkushanova and I decide whether each one is a worthy sample — like food critics judging texture, appearance, and overall impression. Tina is a postdoctoral scientist with the Pollution Research Group, a laboratory headed by Chris Buckley at the University of KwaZulu-Natal (UKZN) in Durban. She’s sampled dozens of pit latrines and directs the worker to get better representative samples.

“Try that one — that looks good,” she says.

I am struck by how composed she is. I realize there aren’t many postdoctoral scientists in the world working directly with shit. Between Tina, Chris, and me, we probably know all of them. Just as sanitation infrastructure in the developing world is lacking, the science of sanitation is trying to catch up.

In recent years, much progress has been made in the science and engineering of fecal sludge management. In January 2015, more than 750 researchers, practitioners, and local government officials converged in Hanoi, Vietnam for the third international conference in Fecal Sludge Management, or FSM3. The first FSM was just six years ago, and the growth in attendee numbers has been exponential.

Several factors were critical for this growth. First, the United Nations Millennium Development Goals set a clear goal for the world to cut in half, by 2015, the proportion of the population without access to adequate sanitation in 1990. While the goal of 77 percent coverage (up from 45 percent in 1990) will not be met in 2015, the act of setting the goal and monitoring progress has led to huge gains. In Eastern Asia, for example, sanitation coverage increased from 34 to 87 percent.

The second big driver for the increased focus on sanitation is the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, which has plowed millions in funding for research and projects into water, sanitation, and hygiene. The result has been new concepts in sanitation technologies, such as the challenge to Reinvent the Toilet — one that is not dependent on sewerage, water supplies, or centralized power and costs less than 5 cents per user per day. The objective is to leapfrog the need for sewer lines and water supply, just as the mobile phone leapfrogged the need for telephone landlines.

But technology alone will not solve the sanitation crisis. First, any innovation has to consider the entire sanitation service chain, including collection, transport, treatment, and reuse or disposal. Second, key factors — behavioral change, clear government policies and regulations, new business models that will allow private entrepreneurs to scale up solutions and profit — need to be addressed. It’s complicated, as FSM people and angst-ridden lovers say.

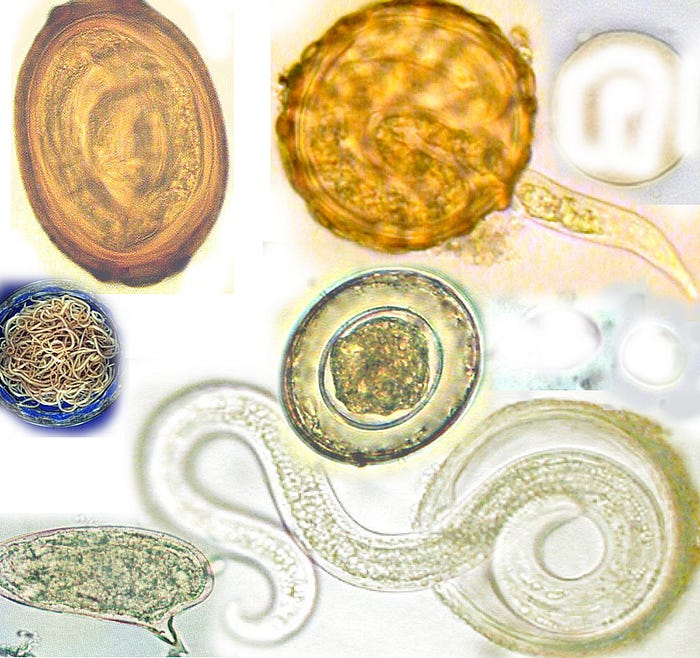

I concentrate on putting our chosen samples in a plastic-lined container, which I then label. Now we have to decontaminate. Gloves go into one trash bag and suits into another, for washing later. Boots are sprayed with a bleach solution. Nothing that touches the samples is allowed to touch other surfaces. In this part of Africa, worm eggs (Ascaris, Taenia, other helminths) are endemic and can be ingested or inhaled. These worms can grow inside the human body and occupy intestines, sucking out food and nutrients from within, like an alien in a sci-fi movie.

I’d been vaccinated for what seemed like everything, including Hepatitis A and B, before being allowed to work in the UKZN lab. Later, I will be given a deworming pill to take after leaving South Africa. Many parents in this region regularly give deworming pills to their kids as a precaution. These parents know that shit surrounds them, whether they like it or not.

Back in the lab, I put on a Darth Vader–like respirator mask and weigh the fecal samples. I extract the DNA from each sample, using chemicals to remove proteins and carbohydrates.

Once back in North Carolina with my samples, we’ll amplify the DNA to make more copies, then sequence it using next-generation techniques to allow us to identify the different microbial DNA present. From there, I can identify microbial community composition and deduce what’s going on in the pit. My research assistants and students will apply multivariable statistical analysis to figure out similarities between samples, note how microbial populations change at different depths, and correlate these changes to chemical and physical changes. I’m hoping that understanding the environment within pits at a very basic level will allow us to design better VIPs or other decentralized systems.

I can’t help but feel scientific research dissonance. I’m applying leading-edge techniques in molecular microbial ecology to analyze samples from a rudimentary pit latrine.

But it’s a gratifying dissonance. In fact, it’s about time we apply the best we have in science, engineering, and social science to the basic problems of the underserved and the poor — and we need more people from these disciplines and beyond to come join me and my colleagues in the fecal sludge adventure. How about you? It’s really not so bad, these shitty days in Africa.

To learn more about de los Reyes and his work, read the full-length interview, “Let’s talk about poo,” on the TED Blog and watch his TED talk, “Sanitation is a basic human right,” below.

The TED Fellows program hand-picks young innovators from around the world to raise international awareness of their work and maximize their impact.