Helen Lewis

‘The suffragettes should not be used as a reproach to modern feminists’

As political movements fade from living memory, they are pummelled and marshalled into neatness. At worst, they become a simple story of good versus evil, with all their agonised debates, bitter personal rivalries and thunderous schisms smoothed out into a easy narrative arc.

But history doesn’t feel like history when it is being made. As a novelist, Hilary Mantel’s greatest achievement has been to put the French revolution and Henry VIII’s break with Rome back into the present tense. She strips away the feeling of inertia from historical events; she makes us see her characters wavering over the road not travelled.

A century on from the suffragettes, we should try to do the same for them. There was nothing inevitable about women getting the vote when they did. It took Switzerland until 1971 to pass universal suffrage, and Saudi Arabia still hasn’t done so (although this year it graciously began to allow women to register to vote in municipal elections). There must have been many moments when the suffragettes felt dejected and downcast.

There is another temptation: to see their fight primarily through what it says about us. That can take the form of congratulations – only a century ago women couldn’t even vote! – or recriminations. Watching the new film Suffragette, written by Abi Morgan and directed by Sarah Gavron, my first impulse was to feel sad that my generation has no single defining cause to rally round. If only we could stop arguing about shaving our legs and wearing the veil and lads’ mags and Lena Dunham and – the list goes on – we could get some real work done, surely?

But that is the distorting mirror of history again. The suffragettes themselves were bitterly divided on several fronts. They fell out over whether all women should get the vote, or just those over 30 who owned property; the debate prompted the Women’s Social and Political Union to split from the nascent Labour party, which wanted truly universal suffrage, and led to a schism between Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughter Sylvia. There were further rows about the use of violence as a political tactic, and bitter struggles over whether the movement was dominated by middle-class women. (We should also resist the urge to see suffragism as an uncomplicatedly progressive, even leftwing, movement. After the first world war – during which many activists campaigned aggressively in favour of military action – Emmeline Pankhurst become alarmed by the rise of Bolshevism. She stood in Stepney in 1927 as a Conservative candidate. Other suffragettes went even further right. Mary Richardson, who slashed the Rokeby Venus in the National Gallery, joined Oswald Mosley’s British Union of Fascists.

In other words, the suffragettes should not be used as a reproach to modern feminists – a symbol of what could be done if women put aside their differences and worked towards a common goal. Instead, they are a reminder of how every revolutionary movement has to deal with personality clashes and internal contradictions. The best tribute we can pay to the suffragettes is to see them as human.

Helen Lewis is deputy editor of the New Statesman.

Tessa Hadley

‘It is as if the suffragettes draw on some deep-hidden reservoir of female rage and wrong’

Women would have the vote now, wouldn’t they, without the suffragettes? Historians these days tend to attribute the eventual achievement of women’s suffrage to the significant role they played in the war economy, and to the longer, slower attrition of the constitutional suffragists, who didn’t engage in direct action. And then the slow tides of economic and social change, moving through the 20th century, brought so many more women into the workforce. It is impossible to imagine a Britain now in which those economically active, tax-paying women weren’t represented in our civic life.

The suffragettes seized our imagination and changed it, however, and that is a part of how politics and history work. And they couldn’t have had half their effect without photography. The records of violent confrontation are unforgettable: Ada Wright collapsed to the ground in her hat amid kicking policemen, or Sylvia Pankhurst feeble from force-feeding, or the terrible picture of Emily Davison tumbled under the hooves of the King’s horse. The Pankhursts in particular understood the power of the image; their portraits seem to have been passed around, collected and adored like photographs of music-hall stars. They were such handsome women: the mother with her Victorian soulful rectitude and set jaw; the daughters with their sprightlier or softer 20th-century beauty.

Some of the shock of the pictures is in how they disrupt the securities of class. Women whose bearing and costume are redolent of privilege and respectability – and those hats! – are screaming and smashing windows, or they are lifted struggling into the air by a couple of policemen. These are scenes of radical openness, and some revelations – of the sheer brutality of misogyny, for instance. Suddenly the world seems to be split vertically, between the sexes, disrupting (for a moment) the lateral divisions of caste. For a moment, anyway. Some of the suffragette leaders (not all) got mixed up in murky politics afterwards. Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst threw themselves enthusiastically into the war effort, distributing white feathers to men in civilian dress.

Much of the good writing at the time was sceptical about democracy, never mind votes for women: the suffragettes in contemporary novels tend to be neurotic or comical. One wonderful exception is Valentine Wannop in Ford Madox Ford’s Parade’s End; she is a brilliant Latinist and a fan of Rosa Luxemburg and a pacifist, and when we first meet her she is being chased across a golf course after haranguing a cabinet minster. Valentine is probably too complex and too critical though – not fanatical enough – to have taken a cleaver to the Rokeby Venus, or even vandalised the orchids at Kew; or for that matter to have carved a V on her chest in prison, or tried to blow up a Dublin theatre. These excesses are significant in our collective imagination. It is as if the suffragettes draw on some deep-hidden reservoir of female rage and wrong: like Bacchantes, almost, or Furies. And so they achieve, at least in our imagination, what their more sensible sisters never did.

Tessa Hadley’s latest book is The Past (Jonathan Cape).

Jacqueline Rose

‘We know in the 21st century that the project of feminist advancement is radically incomplete’

It was, of course, first and foremost a demand for justice and equality. But it was the bodies of the suffragettes that caused the greatest scandal, and one might say, made all the difference, by laying bare what a politically agitating woman – on the street, in the courts, on the rooftops, at the racecourse, in prison, lying prone on the doctor’s table – brings to the surface of the body politic. For the most intense period of the campaign, the decade that ran roughly from 1905 to the outbreak of the first world war, no one could avoid the violence that an unjust society inflicts on half the citizens, or rather the not-yet-citizens, of the world. No one could pretend to believe in two of the most debilitating myths of womanhood, then current – woman’s endearing frailty, and the seemliness of her ways. When news got out of women forcibly stripped in prison, or of campaigning women assaulted in public places with clothing slit with a knife from neck to hem, or of women marched to prison with blood streaming from their wounds after mounted police hurled back at them the slates they had been raining down from the roof of a meeting hall where the prime minister was speaking, the people in the streets, rallying in support of the suffragettes, shouted: “You curs! You would ride over your own flesh and blood!”

There was worse to come. In her 1914 essay on forced feeding – to which she subjected herself out of solidarity – the writer Djuna Barnes pointed out to the doctor that the sheets in which she was wrapped for the procedure looked like a shroud (he agreed). Today, we might read the images of male doctors administering tubes into the throats of women, steel gag pressed against their teeth, as a gross, no doubt unintentional, caricature of sex; not as procreation on behalf of the nation, but as an act of abuse. Nationalism was key. It was at the heart of the sexual fear provoked by the gender-confounding behaviour of the suffragettes. “The progeny of unmanly men [male suffragette supporters] mated to unwomanly women [the suffragettes],” railed one detractor, “is unlikely to last out … in the coming struggle for life between Asiatics, Africans and white men.” Although the simple idea that united them “necessitated”, in the words of Sylvia Pankhurst, “no surrender of prejudice of race or of class”, perhaps the worst outrage of the suffragettes was to show that women’s bodies could no longer be bound to the task of perpetuating the supremacy of the white race.

The slogan “Votes for Women” might, therefore, be as misleading as it was necessary and precise. Because, then, as now, there is no viable way to agitate for feminist advancement – a project we know in the 21st century to be radically incomplete – without keeping other forms of injustice in our sights. For a significant strand of the movement, the struggle for the vote was a struggle on behalf of all the damaged and exploited people of the world. One poster issued by the Suffrage Atelier – “The Appeal of Womanhood” – announced: “We want the vote to stop the white slave traffic, sweated labour, and to save the children.” As Lisa Tickner points out in her 1987 book on suffragette imagery, The Spectacle of Women, a mother, a laundress, a prostitute and a chain-maker can be made out among the group of miserable figures sketched against the towers of Westminster behind. Another poster showed a dark figure, “Starvation”, with her hand on the back of a woman, head bowed, with the inscription “Waiting for a Living Wage” (still waiting, we might say). Sixteen-year-old Dora Thewlis was one of the youngest suffragettes and one of many unsung heroines from the north of England whose story is told by Jill Liddington in her 2006 book Rebel Girls, Their Fight for the Vote. When a Westminster magistrate, Horace Smith, reprimanded her for not being at school, her parents wrote respectfully to remind him that girls of her age in “this part of Christian England” were compelled in their thousands to spend 10 hours a day in “health-destroying factories”, “toiling for others’ gain” in conditions that were sanctioned by law. They saw themselves as outlaws, but it was in the name of a new legal order that they fought: “I am a law breaker,” Annie Cobden Sanderson pronounced in court, “because I want to be a law maker.” When war broke out in 1914, and many suffragettes rallied to the cause, one Florence Lockwood noted in her diary: “War will not help human liberty, I thought, as I folded up the banner and put it away.”

There are, then, many lessons still to be learned. Today women have the right to vote in most countries – Saudi Arabia, great ally of the west, and the Vatican City, at the heart of Europe, being two of the exceptions. But women still make up two-thirds of the illiterate peoples of the world. Everyday sexism, domestic violence, so-called “honour” killing, FGM, rape as a war crime and assaults on women in search of education are more visible today than ever before. And as with the suffragettes, feminists have to be very careful to make sure that lifting these forms of violence against women to the surface of public consciousness does not provoke a thrill at the spectacle as much as human compassion (pleasure not pain). In one sense, the suffragette campaign was simple. The vote was won. But tempering the iniquity of the law has not been enough to secure freedom for women in a world that increasingly thrives on the inequalities of its peoples. Today, women’s bodies are still too often the scapegoats for a world that is as ruthless as it is out of control. This makes the demands on feminism greater than ever before: the ongoing fight for equality, backed by endless vigilance in response to the forms of human perversity which that fight continues to provoke. “The real question,” wrote Harriet Taylor Mill, in words often called on by the suffragettes, “is whether it is right or expedient that one half of the human race should pass through life in a state of forced subordination to the other half … when the only reason that can be given is, that men like it.”

Jacqueline Rose’s books include Women in Dark Times (Bloomsbury).

Sarah Crompton

‘The producer of Suffragette wondered why a film had never been made about the campaign before’

Straw hat tipped jauntily on top of her immaculate blond hair, Mrs Winifred Banks trips up the front steps of her lovely home, humming happily to herself. A sash proclaiming “Votes for Women” is neatly affixed to her immaculate blue gown. No matter that her children have gone missing – she knows what is important. “We had the most glorious meeting,” she announces breathily. “Mrs Whitburn Allen chained herself to the wheel of the prime minister’s carriage. You should have been there. And Mrs Ainsley was carried off to prison, singing and scattering pamphlets all the way.”

Then, because this is a musical, and a Walt Disney musical at that, she breaks into a joyful refrain: “Cast off the shackles of yesterday / Shoulder to shoulder into the fray / Our daughters’ daughters will adore us / And they’ll sing in grateful chorus / Well done, Sister Suffragette.”

The origins of that song in the 1964 film Mary Poppins are entirely pragmatic. Glynis Johns had turned up at the Disney studios, convinced that she was to be given the leading role. To assuage her disappointment, Walt told her a great new tune had just been written for Mrs Banks and she could hear it after lunch; Robert B and Richard M Sherman duly obliged with a smart anthem composed while the actor was eating.

As a new film Suffragette, starring Carey Mulligan as a passionate campaigner for votes for women, arrives in cinemas half a century later, it is strange suddenly to realise that this song for Mrs Banks, dreamed up on a whim, stands as one of the most famous cultural representations of the women who, in the early years of the 20th century, fought fiercely and resolutely for the vote, breaking laws that they believed were unjust and engaging in a campaign of active resistance.

What’s more, the sparky wit of “Sister Suffragette” has helped the musical, full of strong, self-motivated women, to be discussed – with some seriousness – as a feminist tract, a representation of different kinds of womanhood within the candyfloss surroundings of Cherry Tree Lane. Yet in 1964, when women were talking about liberation, and the counterculture was in full swing, it can also be seen as a slap in the face for their ideals – a throwback to the negative image of a suffragette as someone who is prepared to sacrifice everything, even her children, for her beliefs.

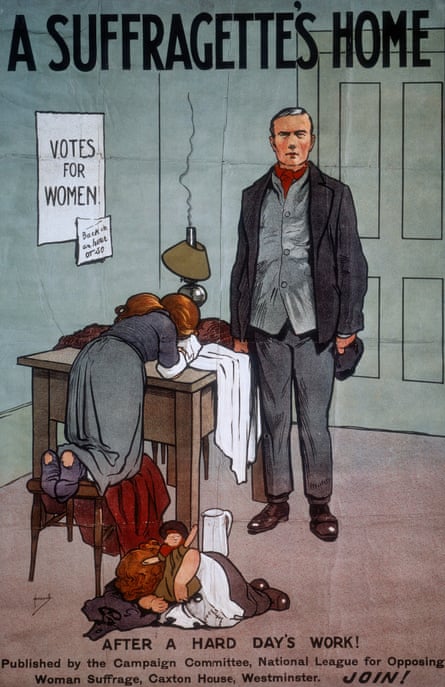

This sense that suffragettes were deserting their rightful place in the home was one of the most powerful smears against them. You can see it in the silent films made at the time, now re-released by the BFI in a compilation called Make More Noise. In one short, a husband is left by his hatchet-faced wife, literally holding a baby in either arm, while she goes off to campaign. His dreams of revenge include putting women in the stocks, or in ducking stools if they offend the great male consensus. We are meant to laugh.

Cinema hit its stride more or less around the time, in 1909, that the WSPU, founded six years earlier by Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia, turned to violence in pursuit of its aims. They began by disrupting meetings and staging demonstrations, then graduated to smashing plate-glass windows, arson and fire-bombing, including an attack on Lloyd George’s half-built country home at the time he was chancellor of the exchequer. The newsreels of the time reveal in flickering silent images the depth of resistance, hatred and disdain they faced. They show 2,000 policemen swarming around a handful of neatly dressed women attempting to present a petition to parliament, and cloth-capped men swamping women who are trying to speak. The Derby day death of Emily Wilding Davison under the hoofs of the King’s horse in 1913 becomes a blur in a newsreel more interested in the result of the race than her doomed protest.

The film Suffragette recreates and reimagines such scenes as the background to its story of laundry worker Maud’s conversion to the militant cause. “I thought there might be another way of living this life,” she says, believing that suffrage will give women the ability to battle more general oppression. This is a theme found, too, in the novels written at the time that – in an ironic contradiction of Mrs Pankhurst’s cry of “Deeds not words” – sought to engage readers through a light fictionalisation of real events. They function for their own age as Suffragette does today; their narratives seek to explain and inspire.

The novel that comes closest to pure documentary is Suffragette Sally by Gertrude Colmore, published in 1911, which concludes with a description of the events just one year earlier after prime minister Herbert Asquith scuppered a conciliation bill that would have given the vote to around 1 million female householders and occupiers. On what came to be known as Black Friday, a delegation of WSPU protesters was brutally attacked by 300 police; two later died of their injuries. In Suffragette Sally, the names have been changed, but the events have not: the kicking of women as they lay on the ground; the assaults on their modesty as skirts were hitched high above their heads; the beatings in the course of 200 arrests.

Although Colmore’s prose is vivid and straightforward, her characters – the Cockney braveheart Sally, the suffragist Edith who believes in peaceful protest but has her mind changed – rarely emerge as more than ciphers. But the stories the novel tells are gripping, particularly its descriptions of the women’s treatment in prison after they go on hunger strike in protest at not being considered political prisoners. Sally’s experiences, which indirectly cause her death, involve her being dragged down metal stairs on her face, her hands handcuffed behind her back, on her way to repeated force-feeding. This actually happened to a woman called Selina Martin, arrested in Liverpool after throwing an empty ginger beer bottle into Asquith’s car.

The stoicism of the campaigners in the face of unendurable ill-treatment has become a lodestone of suffragette mythology. Their passive agony was a weapon against the government as much as the acts that led to their imprisonment, and probably did more to shift public opinion towards them. It makes an appearance in another fictionalised contemporary account, No Surrender by Constance Elizabeth Maud. This is a far cruder book than Colmore’s, although it does have a plot of sorts as its heroine, a Black Country millworker called Jenny Clegg, brings the love of her life round to her way of thinking by her courage and commitment.

In the course of many long conversations outlining the case for the vote and the reasons for militancy, Jenny and her middle-class friend Mary O’Neill have to face down not just sceptical men but also the “Antis”, the women who opposed the extension of the franchise and criticised the militants for their unladylike behaviour. A Miss Crompton is particularly odious. She exclaims: “Helpless women! That is the last way you could describe those viragoes. They kicked and scratched and hit out with umbrellas. They would have killed those unfortunate stewards if they could.”

For all its clumsiness, No Surrender reeks of authenticity and of stories begging for a hearing. It is odd then, in the years since women won the vote, that their struggle has found so few cultural manifestations. A rather unsympathetic suffragette – another neglectful mother – finds a place in Tracy Chevalier’s novel Falling Angels; the deeply sympathetic Catherine Winslow reveals the true meaning of love and sacrifice in a vignette in The Winslow Boy, where Terence Rattigan’s compassion makes her radicalism part and parcel of her willingness to stand by her family. In Up the Women, a TV sitcom launched in 2013, Jessica Hynes managed to wrench laughter out of subjects such as hunger strikes and Mrs Pankhurst (a star turn in a large hat by Sandi Toksvig), while simultaneously honouring the history and the women who were prepared to stand up for their rights even if only “politely requesting” them. Otherwise, there is not much, as the makers of Suffragette have noticed. “We wondered why no one had ever made a movie about the suffragettes,” producer Alison Owen has said.

The comparative silence on the subject may be caused by the fact that although the broad brush strokes are dramatic, the detailed history is immensely complex. It is also far from straightforward, particularly when it comes to the divisive effects of the Pankhurst family on the movement they led. That is why the key suffragette text for anyone growing up in the 1970s was the 1974 series Shoulder to Shoulder – six 90-minute episodes of closely argued and beautifully acted TV drama that told the story, from prewar beginning to postwar end, warts and all.

The series has the scope and the courage to replay the political intricacies of the struggle – and the complex personalities that forged its shape. The demonstrations, the hunger strikes and the growing militancy are all searingly charted; the scenes in which we witness Emily Davison’s fanaticism grow as she is subjected to the most incredible cruelty are all but unwatchable. So is the distress of Constance Lytton, played by Judy Parfitt.

But questions about the conduct of the campaign are also raised. Siân Phillips is a memorably charismatic Emmeline Pankhurst, but her willingness always to support Patricia Quinn’s self-centred and ferocious Christabel is revealed as a weakness as well as a strength. Their ruthless determination that all the women had to obey their decisions – “We must march in step like an army,” Christabel proclaims – means their party fragments even as it moves forward.

It feels significant that Shoulder to Shoulder emerged in the era of Spare Rib, when women were once more discussing the nature of activism and different and sometimes competing definitions of feminism and its relation to the wider politics of the time. Forty years later, a new view has emerged: Suffragette is a perfect film for a generation that has lived through post-feminism and now begins to think that perhaps they will have to fight once more for full equality. It clearly seeks to inspire, smoothing over difficulties, full of passionate indignation on behalf of women, ending with a roll call of the years in which they won the vote.

This is a film that deals with the arguments about the campaign of increasing violence in a single sentence – “the movement is divided now. Even Sylvia Pankhurst is opposed” – and Mrs Pankhurst (Meryl Streep) only appears in one brief scene. Although it pays obeisance to the fortitude of the women in prison, its real interest lies not in that passive suffering, but in showing women as bold activists, surrounded by men who want “to bring these bitches to their knees” yet capable of taking their destinies into their own hands. Each generation takes a view of the suffragettes that suits its needs. The story is both of its time and timeless, a history that mustn’t be forgotten and whose lessons will always be relearned.

Sarah Crompton is a writer on arts and culture.

Rachel Holmes

‘It was working women who taught their middle-class sisters how to organise and bargain’

As Sylvia Pankhurst’s biographer, it is my duty to be blunt. She never thought Votes for Women her greatest achievement. “Granted,” she said, “the vote has brought an all-round improvement in many directions,” but “the improvement has been gradual rather than dramatic.”

Some say the suffragettes, led by the Pankhursts, marched out on Millicent Fawcett’s moderate voting reform campaign in 1903 because, like so many freedom fighters, they realised they wouldn’t achieve their goals by legal, peaceful means. Militancy, the story goes, did the cause more harm in the end. In reality, there was no choice – patriarchy had been at war with women for a millennium.

Militant tactics were acts of self-preservation; resistance against the violence and aggression of institutionalised gender discrimination and abuse threatening women’s lives and minds. Suffragettes refused to be victims. Women of all classes had swallowed the myth that they were second-class humans fit only for reproduction and subordination in male society. The violent deeds, not just words, used by the suffragettes expressed political revolt against the external edifice of domination. They were also an intimate revolution against the internalised oppressions inhibiting women.

Great strength came from politicising their bodies. An army without guns, they employed methods of non-cooperation and non-violence. Hunger-striking, window-smashing, arson, bomb-throwing – their bodies and voices became sites of resistance. They shaped modern feminism.

Suffragettes dared to believe in themselves and to act as the equals of men. To become a serious threat to the social order, they had to be fearless. To make women agents of change in every aspect of our politics, society and culture, they had to endure personal sacrifice. They lost jobs, homes, families, children – and their lives. This legacy of necessary sacrifice sits uncomfortably with some of our current “we-can-have-it-all” forms of feminism.

Suggestions that suffragettes were mostly posh are historical nonsense. As brilliantly depicted in the film Suffragette, working women weren’t only foot soldiers of the movement but also its leaders. Many were already in trade unions campaigning for universal suffrage and equal pay for male and female workers from the 1800s.

There is a tendency to perceive the suffragettes too narrowly. Fawcett said smugly in 1911 that her reformist movement was “like a glacier; slow moving but unstoppable”. She forgot that glaciers evaporate, melt and retreat. The suffragettes who understood theirs as part of the broader fight for equality, democracy and social justice – not a single-issue struggle – are far more relevant today than their sepia-tinted gradualist sisters. Hence Sylvia Pankhurst’s observation on the doomed character of attempts at partial change not built on a broad-based and progressive movement.

Suffragettes learned the power of collectivism. Crucially, it was working women who taught their middle-class sisters how to organise, assert collective rights and bargain. The suffragettes had modest legislative success. Their militancy was controversial, not least in their own ranks. Their achievement was to force attention to their cause and occupy public consciousness as never before. We have yet to finish the job they started.

Rachel Holmes’s most recent book is Eleanor Marx (Bloomsbury).

Bridget Christie

‘The suffragettes were slightly more committed to the emancipation of women than I am’

Apparently, Jimmy Savile didn’t run all the charity marathons he said he did. He would run for a short distance, then jump into an ambulance or some other type of flashing, wailing, inconspicuous emergency service vehicle and be driven, by a headless coachman, to somewhere near the finishing line, hop out and run the last bit.

Earlier this year, my left foot got jammed in a long, narrow pothole in the road. I didn’t see it because I was distracted by a text telling me that Mary Beard had sent a tweet out saying my routine about her was hilarious. I tore all the ligaments in my ankle, broke my finger and had to have my engagement and wedding rings sawn off. They’re still in pieces in the urine sample bottle the nurse put them into for safe-keeping. I expect Beard, the feminist, loves that.

About a month later I was asked by Helen Pankhurst, great-granddaughter of the leader of the suffragettes Emmeline Pankhurst, to take part in a panel discussion on International Women’s Day, and to walk with her in solidarity with all the women around the world facing inequality and injustice. I was incredibly flattered and honoured – it was like a descendant of Jesus had got in touch.

The walk was to launch 2015’s Walk in Her Shoes campaign for Care International, where Helen is a senior adviser, and many brilliant women attended a mass walk along London’s South Bank. Arm in arm, they remembered all the thousands of women and girls around the world forced to walk for water all day long. I didn’t, though, because my ankle was throbbing. I did the talk, then got a taxi to the end of the walk. I am the Jimmy Savile of feminist campaigners. And I am ashamed.

The suffragettes were slightly more committed to the emancipation of women than I am. Kitty Marion, the music-hall entertainer and militant suffragette, was force-fed more than 232 times in prison for her beliefs. On the night of the 1911 census, Emily Wilding Davison hid in a crypt at Westminster overnight so that on the census form she could legitimately give her place of residence as the House of Commons. The suffragettes blew up houses, smashed windows, burned down unoccupied buildings, poured chemicals into mailboxes and chained themselves to railings outside Buckingham Palace. They were imaginative, passionate, fearless, dignified, good-humoured and extremely well organised. I deserve to have my T-shirt with the suffragette motto “Deeds not words” written across it ripped from my back and thrown into a bin.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion