‘There is a place on the other side of every door. And as long as the door is closed, you do not know what is on the other side. Where do I find my stories? It is there that I find them: the other side of the door,” says Tonke Dragt. Physically fragile and very private, the 84-year-old children’s author rarely goes far from the sheltered accommodation in The Hague where she now lives, and it is even rarer for her to agree to any kind of media attention. She perches on the edge of her bed to be interviewed, wrapped in a wildly patterned cerise kaftan like a delicate, exotic bird, and flicks easily between Dutch and English for a couple of hours before getting weary.

Although a star in her own country, she is virtually unknown in the UK. But that’s slowly changing with last year’s English translation, the first ever, of her 1962 adventure story The Letter for the King (De Brief Voor de Koning) and, this month, the appearance of its sequel, The Secrets of the Wild Wood. The Letter for the King is a Dutch classic, winning the country’s children’s book of the year award in 1963 and, in 2004, the “Griffel der Griffels” for best children’s novel of the past 50 years. Translated into many languages, it has sold over a million copies worldwide.

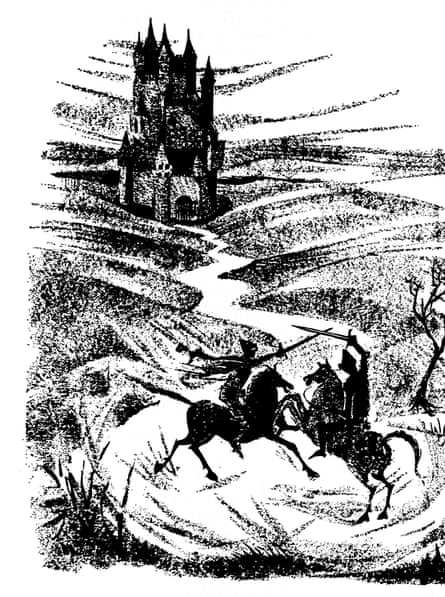

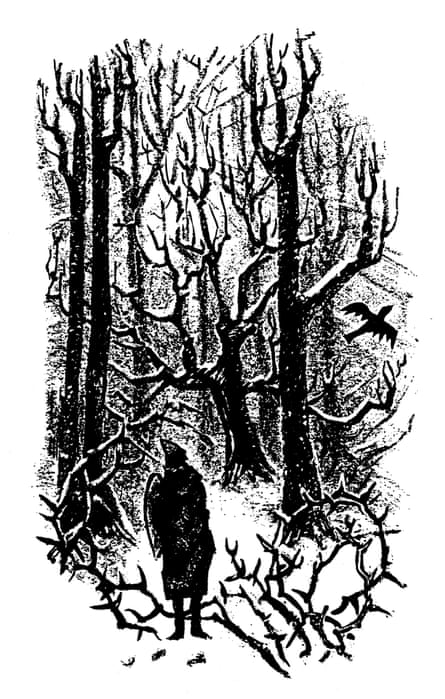

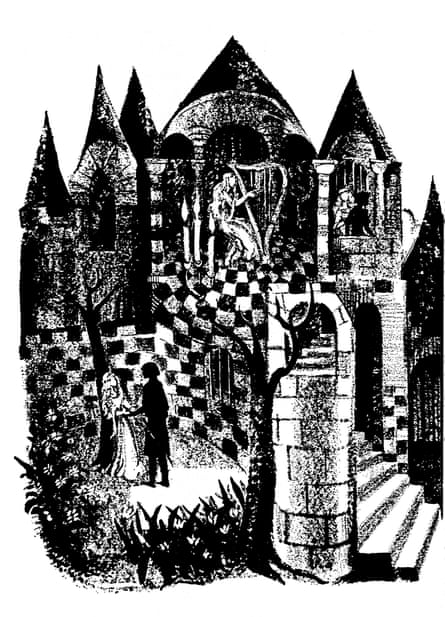

It does indeed begin on the other side of the door. Set in the middle ages, it’s a coming-of-age tale that opens with 16-year-old Tiuri, who has been confined to a chapel for a night of prayer before being made a knight in the morning, hearing urgent knocking and a plea from behind a door. Although he has been given strict instructions not to leave the chapel, on pain of losing his knighthood, his conscience does not allow him to ignore the appeal of someone who may need help. He anxiously opens the door to a mysterious stranger, who hands him a sealed letter and gives him a secret quest that takes him across mountains, through forests and rivers, hunted and waylaid, all the way to a mythical kingdom and into adulthood. The Secrets of the Wild Wood continues the story of (now Sir) Tiuri and his friend Piak as they tackle another perilous mission. Oh, and growing up and falling in love along the way.

Dragt, who still receives letters from children signed from Tiuri and Piak, is modest about the enduring appeal of the book. “It’s crazy,” she says, wonderingly. “It’s a very old book, in many senses. It’s not bound in time and place, it’s a fantasy that takes place in the middle ages. It’s an archetypal sort of story, a very simple sort of story.”

It’s been described as a spiritual tale, despite Dragt firmly stating that she is “not a believer, not a Christian”. It is certainly a moral tale with honour – and the power of truth, justice and friendship – at its heart. It is also action-packed. As with many of Dragt’s stories, the cliffhanger chapter endings in the book were born from oral storytelling. When she worked as an art teacher in The Hague in the 1950s, her pupils were “very tiresome and talkative”. She discovered that she had the power to make them fall silent by inventing stories as they drew their pictures – and promising that if they stayed quiet she would tell them the end of the story. “And that was the beginning of my career as a writer,” she smiles.

“Once I told the story of how a boy opened a door to a plea of help. I made up his name on the spur of the moment and gave him a letter but without having the slightest idea of what was in the letter or how it would end. It was the last day of term and all the children listened to it open-mouthed. Then, in the holidays, I began to write it down and it was The Letter for the King.”

The book was her second to be published – followed by many others, most notably the science fiction story Torenhoog en Mijlenbreed and the contemporary De Zevensprong, all illustrated by Dragt herself – and she quickly achieved a level of success that enabled her to give up teaching and write full-time.

But she had been telling stories for many years before that. Born in Jakarta in Indonesia (then the Dutch East Indies) in 1930, she was the eldest daughter of a Dutch government employee; in 1942, she was interned for three years, until the age of 15, in a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp.

“I discovered that I could write stories in a concentration camp where there was nothing,” she says. “I wrote stories there for my friends, full of heroes who were prisoners who could escape. That was the first time I made my own stories. There were no books there. I also tried to draw – in the sand, on the walls … there was no paper.”

Dragt, her two sisters and their mother were in a camp of 10,000 women and children, while their father was a POW in another camp; he eventually found them after the armistice using a Red Cross list: “For three years after the war, we didn’t know if he was alive or dead,” she recalls. “All the white people had to be in camps – you were the enemy. And it was safer, later on, in a camp than outside. Though there was not enough food in the camps. I was very hungry. Hunger was everywhere.”

She was not “very” scared, she says, which she then qualifies with memories of the “crazy, moonsick” camp commander who, when there was a full moon, would order all the prisoners to get up in the middle of the night and stand outside for hours.

“We had what they call ‘concentration camp syndrome’ [a type of post-traumatic stress disorder] after the war but they didn’t really know what it was then – everyone had been in camps during the war and years later people talked about how bad it was but, to begin with, everyone was just glad that the war was over and people didn’t want to look back.”

After a second spell in Indonesia, her family moved back to the Netherlands for good when she was 18, where she attended the Royal Academy of Art, training to be an artist and a teacher. She illustrated books by authors including E Nesbit, Alan Garner and Rosemary Sutcliff, then started selling her own stories to magazines. Her work is often inspired by her childhood in Indonesia – the woods in The Secrets of the Wild Wood are based on her memories of the tropical forests of her youth. “I didn’t like Holland at all in the beginning – it was cold, it was flat and it was full of houses and people. It was just after the war and we were strange,” she explains.

The neat two-room apartment in a care home complex in The Hague, the city she has made her own since leaving Indonesia in her late teens, is apparently a far cry from her own, more chaotic, home, in which she lived alone for most of her adult life. It had been crammed to the rafters with treasured possessions but now she is, at least, surrounded by books, her own artwork – she specialises in collage – and doll’s houses that she painstakingly fills with extremely surreal tableaux. It becomes clear that Dragt has always lived her life as an outsider in one sense or another – first in Indonesia, then in The Hague, where she was “not really Dutch”, and then, later still, in her choice of literary genre – fantasy – which was seen as “exotic”.

“In Holland it was very difficult for me to get a publisher – they wanted realism, realism, realism! Fantasy wasn’t in – they were seen as crazy books, full of crazy knights with crazy names,” she says. She has long admired the English fantasy tradition, to the extent that when she first read Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings (after she had written The Letter for the King), she was unable to write for six months for fear of being influenced by him.

“I tried once to write a very realistic story, so I wrote a story about a class of children who went somewhere on a bus and within two chapters they were flying in the air – it’s the way my mind works! I’m a fairytale teller,” she says firmly. “I was born like that and I cannot do anything else.”

That The Letter to the King and its sequel feel so very “English” in so many ways makes it all the more surprising that it has taken over half a century for there to be an English translation, even given the UK’s infamously low levels of interest in fiction from non-English-speaking countries (a meagre 1-2% of children’s fiction available in the UK is in translation). The books’ translator, Laura Watkinson, who took the initiative in suggesting Tonke Dragt as ripe for the UK to Pushkin Press, says: “I’ve always been puzzled about the English-speaking market’s relatively low levels of acceptance for children’s books in translation, even after the long-term success of such translated classics as The Moomins and Pippi Longstocking, for example. It’s almost as if people think those books must originally have been written in English, as they didn’t seem to have paved the way for many more great children’s books to be translated, with the occasional exception over the years. I couldn’t understand, in particular, why The Letter for the King had never made it into English, even with so many champions. It fits so well with the English children’s canon too.”

For Adam Freudenheim, the publisher of Pushkin, which specialises in translated fiction, the appeal is straightforward. “The plot is extremely gripping and the short chapters make the book very easy to read and read aloud – I read most of The Letter for the King out loud to my two older kids, who adored it and begged me to read more every night. I knew then that I was on to something,” he says. In fact, Freudenheim’s son Max, then eight, was so desperate to know what happened next that “he crept into our bedroom at four in the morning, quietly stole away with the bound proof and proceeded to read the last 150 pages or so himself before we woke up.”

There is also now to be a TV series inthe UK – after The Letter for the King was acquired by a production company, which is developing the book for the BBC.

No longer the outsider, Dragt was awarded the State Prize for Youth Literature in 1976 and was herself knighted in 2001. What does it all mean to her? She smiles. “Success means being able to write the books that you want to write – the ones that some people will love and others hate but nobody will feel indifferent about.”

Tonke Dragt’s The Secrets of the Wild Wood, translated by Laura Watkinson, is published by Pushkin Press. To order it for £12.99 (RRP £16.99) go to bookshop.theguardian.com or call 0330 333 6846.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion