Can “Makers” Really Remake the American Economy?

Back in ye olden days, they were craftsmen. (And –women, obviously.) Then, during the rust-flecked golden age of Big Industry, they seemed somewhat obsolete. But in the last decade, we’ve seen the cultural rise of the “maker”: a loosely defined term, often thrown around recklessly, for small-scale, artisan production of physical goods. In Portland, we have our brewers and leather crafters and small-batch chocolatiers—a miniature nation of “makers.”

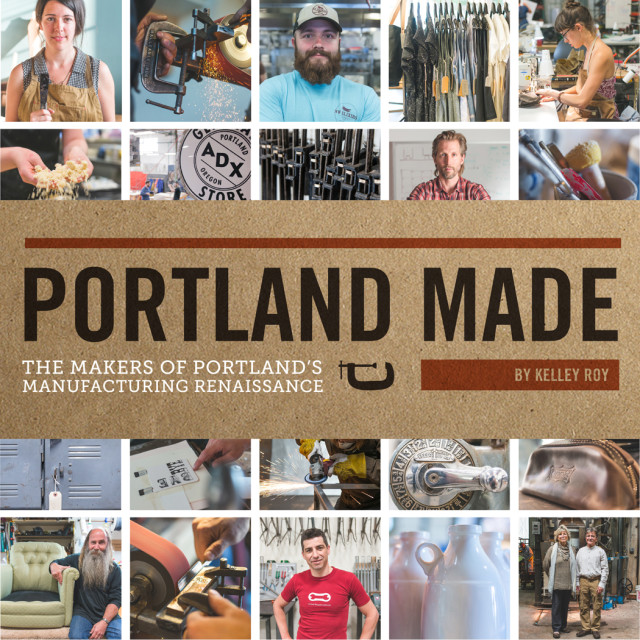

But can makers make an actual difference? Can the term transcend trendiness to become a marker of real economic heft? In Portland Made, a forthcoming book now the focus of a crowdfunding effort, longtime Portland entrepreneur Kelley Roy argues that the answers are yes. The book promises a portrait of our local “manufacturing renaissance,” and something more: a case for small (and sometimes beautiful, per the rebel-economics classic by E.F. Schumacher) producers of consumer goods as a new economic backbone for more vibrant communities.

Ambitious? Yes. Roy’s book combines journalistic portraits of Portland success stories like bike-parts manufacturer Chris King and ice cream sensations Salt & Straw with essays pushing an economic and social argument too seldom heard in American politics. “The maker movement is changing the way we learn,” she writes in the afterword, “and reminding people about the power of working in community.” By nurturing a diverse ecosystem of small-to-medium-sized companies engaged in producing high-quality goods, Roy suggests, cities (and even nations) could revive their middle classes and provide a new path to prosperity.

“It feels like there’s momentum building in Portland,” Roy said in an interview. “It just feels like there’s this thing building.”

Roy presides over a significant hub of that “thing” at ADX, the membership-driven workshop in Southeast Portland where aspiring (and, indeed, established) makers can access communally owned tools, classes, and other resources. “There seemed to be a real hunger for a raw creative space where people could get together,” she says. “There have always been spaces like that around Portland, but really no one behind them to give them structure and intention and power. I like seeing things happening all over in a disconnected way and bringing them together.”

ADX is hip in an updated-punk-rock way: a new, sawdusty embodiment of time-tested DIY values. But Roy insists the movement she’s trying to document (and simultaneously define) is much larger. In a a voluntary survey she conducted with Portland State economist Charles Heying, she says, 126 companies that fit her broad definition of “makers” reported employing 1,100 people and generating $270 million in economic activity. Extrapolate—to her estimate of 10,000 to 15,000 small-scale manufacturers in Portland, for example—and you have a force that should wield political influence, but doesn’t.

“If Nike or some other major employer comes to a city and says, we’ll employ X people, they typically want tax breaks for that,” she says. “That’s doing us in as a country. This is about trying to think about a different basis for an economy—a collection of companies, not just one company.”

Portland Made, which will get a post-publication showcase at Powell’s in December, is one attempt to push for that transformation. It’s a big job, but someone’s gotta do it—and this book makes a good start.