In the US, where it has topped the New York Times bestseller list over the summer, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s book Between the World and Me has been hailed as the unmissable document of the current #ICan’tBreathe state of race relations. (The New York Times said it was “essential, like water or air.”) Coates, 39, a staff writer at the Atlantic magazine, conceived of his book as a letter to his teenage son Samori, just as 50 years ago, James Baldwin, the great poet-prophet of the civil rights movement, wrote his seminal work, The Fire Next Time, as a missive to his young nephew.

Coates’s book is a profound and angry address to a nation that refuses to prosecute police officers who kill innocent black men and women; that pursues a policy of mass incarceration hugely weighted towards its black population; and that routinely seems to think nothing of it. It is also an intimate confession of the fears of a black American father, fears that whatever positive values he gives his son, however hard he encourages him to work in school and do the right thing, out on the streets his body, the colour of his skin, will make him vulnerable to state-sanctioned attack. Coates has heard Samori weeping in his bedroom after watching the night-time news. The book is a response to the sense of powerlessness, and fear, that evokes in him.

“I write to you in your 15th year,” Coates explains by way of introduction. “I am writing to you because this was the year you saw Eric Garner choked to death for selling cigarettes; because you know now that Renisha McBride was shot for seeking help, that John Crawford was shot down for browsing in a department store. And you have seen men in uniform drive by and murder Tamir Rice, a 12-year-old child they were oath-bound to protect. And you know now, if you did not know before, that the police departments of your country have been endowed with the authority to destroy your body. It does not matter if the destruction is the result of an unfortunate overreaction. It does not matter if it originates in a misunderstanding… Sell cigarettes without the proper authority and your body can be destroyed. Resent the people trying to entrap your body and it can be destroyed. Turn into a dark stairwell and your body can be destroyed. The destroyers will rarely be held accountable. Mostly they will receive pensions. And destruction is merely the superlative form of a dominion whose prerogatives include friskings, detainings, beatings and humiliations. All of this is common to black people. All of this is old for black people. No one is held responsible.”

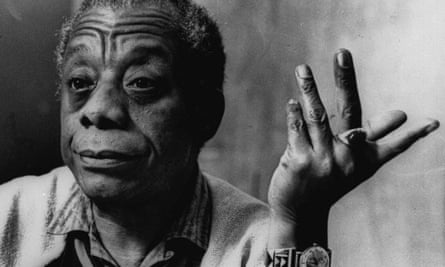

It is Coates’s contention in the book that despite civil rights, despite the symbolism of Obama, violence towards, and subjugation of, black men and women remains ingrained in American culture from slavery. The denial of that fact is part of the “Dream” by which, in a phrase borrowed from Baldwin, those “who believe themselves to be white” maintain power and righteousness. The book is extraordinary both for the depth of its feeling and the unusual power of its writing – Coates is an atheist, but inhabits the cadences of the great religious orators as well as the voices of his literary heroes, Baldwin and Richard Wright, and mixes in some of the verbal inventiveness of hip-hop with which he grew up. Toni Morrison, who knows something about the language of provocation and wisdom, suggests that “its examination of the hazards and hopes of the black male life is as profound as it is revelatory. This is required reading.”

I met Coates a couple of weeks ago in a cafe in Paris, where he has decided to live for a year with his wife and son. It is his son’s first day at his new school and Coates is a little preoccupied by the fact that he will be the only English-speaker in his new class. One of the conclusions of his book, its pessimism about the circumscribed nature of black American life, is that escape is one option. He remembers nearly a decade ago his wife wondering aloud if they should consider a move to Paris. She subsequently took a trip and came back full of hopes and stories and with a stack of photographs of the French capital’s enormous doorways, with which she had become fascinated. Coates, who at the time had never had a passport himself, examined these pictures in their cramped Harlem apartment. “It had never occurred to me that such giant doors could exist, could be so common in one part of the world and totally absent in another…” The doors looked a lot like a symbolic way out. Some years later, while writing his book, Coates made a trip himself, and was entranced above all by the freedom, the absence of fear (“because my eyes were made in Baltimore, because my eyes were blindfolded by fear”) that he felt as an “alien American” in Paris. The family came over for a summer, and now they have moved here.

I wonder first, if that original liberating feeling persists? “It does,” he says. “I fell in love with it here and I still feel that. I like the distance. It’s helpful for me. It is interesting for me to be here and to be seen just as an American, primarily that. I talk and that’s my identity. It is a very different mask to back at home.”

It took James Baldwin, another exile in Paris, that same distance to reveal a truer understanding of his native country. Coates only did the final edits of his own book in Paris, but was that context part of the appeal too?

“It was, and it is helpful,” he says. “The lines around race are much, much harsher at home. I am not saying they don’t have issues around racism here or in London or wherever, but racism in America is very, very sexualised.

“I haven’t fully worked that out but I think the way people actually came to be in America, through sexual violence, really has affected how black folks are seen. It is not the same as an immigrant population, as someone who just happens to be from somewhere else. Especially down south. There was no United States before slavery. I am sure somebody can make some sort of argument about modern French identity and slavery and north Africa, but there simply is no American history before black people.”

I guess one other aspect of his chosen exile is that it removes him somewhat from the attention his book has afforded him. That attention has gone right up to the White House, where Coates has been invited a couple of times to put his views to the president. He has taken Obama to task for not being more vocal on race issues; the last time they met the president took him to one side to deliver a simple message: “Don’t despair.” He tries not to; instead he trusts in his writing to make a difference. He has a vivid blog about the issues he sets out in his book, and continues to write for the Atlantic – this week a long story about American prison policy has, he hopes, “kicked up some more dust” – but he has no wish to be a talking head. He wrote the book, he says, because he felt he had no option not to, the news of last year being so bad.

“I am a little surprised to be honest by the scale of the reaction to it,” he says. “My editor said he had never seen anything like it. I can’t explain it. Expecting a reaction is almost contrary to the idea of writing over a long period of time. I don’t know. I was like a doctor trying to deliver a baby – you can’t imagine that kid at 18. I just wanted to deliver the baby successfully.”

It is, I say, a different kind of voice to most of his journalism, that richness of language; it almost demands to be spoken out loud. Was that the plan? “I didn’t start off as a journalist, I started off as a poet,” he says. “My ambition was to practise poetry. Then I found journalism but that other voice never fled from me. See, everybody makes the James Baldwin comparison, and they think it is a political comparison. They say you are saying the kinds of things he was saying. But it’s not that. Or at least that is not the thing about Baldwin that inspired me. It’s more Baldwin understood that if you are going to say something important about the world it is best if you try to say it beautifully. I don’t mean like picking flowers or writing on fancy stationery. I mean how you say it actually makes it a more meaningful piece of writing. I am going to push that further. It makes it a truer piece of writing. What you are saying is: ‘Can I make somebody feel this in a deeper way?’ That was what I was obsessed with.”

Did that voice come easily? “Hell no. I wrote at least three complete drafts.” Was he adding poetry or taking it away? “It was stripping away. The early drafts were more flowery. The effort was to say more with less.”

The fact was, though, that he felt he had no choice but to do it. One impulse was a proper response to the protests in Ferguson, Missouri and New York and elsewhere – that and the fact he returned to reading The Fire Next Time, on its 50th anniversary, and found it spoke differently to him, more urgently perhaps than it had done before. “It’s easy to forget Baldwin was a journalist,” he says. “I mean he is interviewing [Nation of Islam leader] Elijah Mohammad and others in that book. It is not him sitting on his ass in Paris saying this is how I see the world.”

I point out that Baldwin was 39, like him, when he wrote it. Coates Googles to check; he thought Baldwin was younger. And I suggest that both books feel like mid-life books, not only in the sense of personal crisis, but also in that they are expressions not of the anger and hope of youth, but of the realism and anxiety of pushing 40.

“That’s about right,” he says. “I mean I read Baldwin when I was at Howard [the predominantly black university in Washington DC that counts many civil rights heroes and intellectuals among its alumni]. But it has taken until now to really get it. At the time, people were very excited about that crop of black intellectuals, Cornel West, Henry Louis Gates. They were wonderful thinkers but no one would claim they were beautiful writers. I read Richard Wright, James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Sonia Sanchez. I would think about that shit for days. Those phrases stayed with me in my head you know, like Sanchez: ‘Do not speak to me of martyrdom/of men who die to be remembered/on some parish day./I don’t believe in dying/ though I too shall die/and violets like castanets/will echo me.’

“I mean: wow. It was so beautifully said. It took me a while to realise she was talking about Malcolm X. They shot him. There is immense grieving in that. And that seemed very relevant.”

University seemed to have offered Coates a way out of the quite brutalised life he had known as a child in Baltimore, where, as he recalled in his first book, a memoir called The Beautiful Struggle, a large part of his mental space was occupied by how to get safely to and from school in neighbourhoods where murderous gang violence had become the norm. As it was, he realised that escape was not so simple: a friend and peer of his at university, Prince Jones, a straight-A student, hoping to be a doctor, was shot in the back and killed by a plainclothes policeman in a case of “mistaken identity” in 2000. The officer was not prosecuted and kept his job. The sanctioned murder of Jones haunted Coates’s understanding of American life, and resurfaced with the spate of police killings in recent years. Some of the most moving passages in his book involve him going to see Dr Mabel Jones, his friend’s mother, whose loss and anger remain raw. It took all of that for him to get James Baldwin, nearing 40, and to fear for his own son’s life as he had once feared for his own, and to write.

“It’s like that phrase of Baldwin’s I use in the book,” he says: “‘Those who believe themselves to be white’: because once I got it, once I understood what he was saying, I thought it was the most beautiful thing I ever heard. What it does is introduce the idea of human agency into race. This shit isn’t natural, and it’s not accidental. There was a decision that was made here. And I realised beautiful writing could make you feel a certain way and you could carry those feelings in you for a long, long time. I really, really wanted to do that.”

What does Coates’s son make of the book that is addressed to him? “He likes it. It was not like it was a finished book and I handed it to him. He read it. He read a draft even before I turned it into a letter. And I asked him about doing that and he said sure. I would not have done it without his saying yes. I can’t yet see what he will make of it or do with it. He’s too young. I will know in 10 years.”

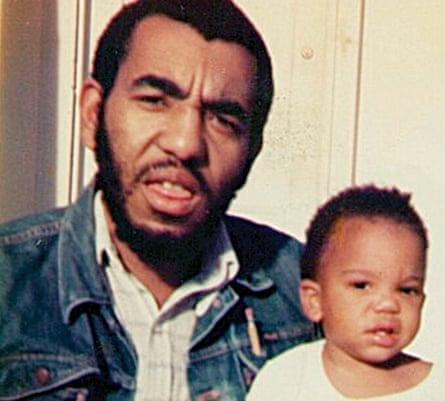

One of the reasons Coates thinks a lot about fathers and sons is that his own father, Paul Coates, tried to school him in similar ways. The substance of The Beautiful Struggle – a kind of hip-hop Portrait of the Artist, denser in its poetry than the new book – is the story of their relationship. Paul Coates was a Vietnam veteran and member of the Black Panther party, a follower of Malcolm X, a self-taught historian of black struggle in America and an obsessive collector of books that told the story of that history. When Coates himself was a boy, his father started a printing press and cottage publishing industry in their house to disseminate some of these stories in Baltimore and beyond. Paul Coates had six other children, practised free love, but unusually among his schoolfriends, Coates recalls, his father was ever-present in his childhood, encouraging him to read, encouraging him to write, and occasionally delivering brutal beatings when he strayed, justifying himself to Coates’s mother by asking: “Would you rather I did it or the cops?”

“My dad always associated information with liberation,” Coates says. “He was very much in that Malcolm X tradition. I mean the story of Malcolm’s life was almost mythical. This guy goes into prison and he liberates himself through knowledge, finds a profound understanding of himself and his situation. That was an immensely powerful idea for men like my father. It was his version of the story of Jesus. He talked about it the way people talk about the crucifixion. You may not be able to change the course of government, but you can achieve some peace. And books were the path to that. I grew up in a house where books were everywhere. The authors my dad liked, the authors he likes, were all, like him, self-taught. He is talking about retiring at the moment but I think he might do it till the day he dies.”

His dad must be proud of Coates’s achievements? “Yes, he is very proud. And I am extremely pleased to have made him proud.”

You have become what he hoped you would become? “I don’t think he had any idea this was possible. I think he would have told you Ta-Nehisi is a smart kid he could get somewhere. But this is certainly beyond my imagination, and his.”

I wonder how much Coates felt himself in the tradition of that Black Panther movement that his father helped to organise, which advocated armed struggle as one means to achieve fuller liberation? “Violence was definitely part of it,” he says. “And that was powerful for me as a child, as I say in the book. Guns were romantic, right. But they were also part of the language that I recognise my country speaks. That is how we talk in America. The memoir was an attempt to take everything I was as a child, everything I had seen by the age of 19 or 20 and mash it together and try to find some kind of creative voice out of that.”

His experience of Baltimore at that time, he says, was very similar to that portrayed by David Simon in The Wire, a city falling apart because of the arrival of crack cocaine and abandonment of whole neighbourhoods by civic authorities. One way out was music: Coates’s first aspiration was to be a rap artist.

“Hip-hop was really the first literature I studied,” he says. “I tried to do it. But I wasn’t very good. It is extremely hard, it is not just a question of coming up with words that rhyme. When I first read Shakespeare, I fell in love with Macbeth. There was a particular scene where Macbeth is talking to the murderers, trying to get them to kill Banquo and they agree. ‘I am one, my liege, whom the vile blows and buffets of the world have so incensed that I am reckless what I do to spite the world.’ That sounded to me just like a rapper would describe his life. I’m just so beat down I don’t give a fuck. Bring it on. That is the core message of hip-hop right there. That realisation said to me there is something human in this, that desperation that is expressed there can’t be bounded by time, or place, or society, or race. It is a deeply human feeling.”

The act of articulating that feeling is, in a sense, the only hope that he offers Samori in his letter to him. The necessity is to understand the nature of the struggle, the way the land lies, and to be able to express it. Did he himself feel better for doing so? “Was it cathartic? I don’t know. I felt better that it was said. I didn’t want to walk around with it.”

In person Coates is warm and relaxed, full of intellectual energy, but his book is short on solace or solutions or much in the way of optimism. It preaches a gospel of brutal truths about race, and stresses the importance of acknowledging them as an aspiration in itself. Despite the fact of a black American president, despite the media focus on the protest against police killings, he sees no prospect of much change, at least not until America acknowledges the facts of its history. It is, I suggest, an argument above all against the requirement to be hopeful.

“Yes,” he says. “But I’m a writer. I have no responsibility to be hopeful. This is literature. I don’t need to be arguing that in five years we are going to turn a profit. I don’t need to look for redemption.”

But in America in particular, doesn’t that need for redemption, for optimism, run deep? “Yes and I think that it is deeply injurious to us all. If all your movies and all your stories have to end with the good guy winning on some fundamental level, your culture is not being honest about the world. My job is to look out and see what I see and to be just as honest as I can.”

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates is published by Text Publishing (£10.99). Click here to order a copy for £8.79

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion