You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

iStock/Ebrusa

The eighth edition of the Modern Language Association’s handbook created quite a lot of chatter upon its publication last year -- and rightfully so -- both on my campus and in the academic press.

Inside Higher Ed outlined the changes as they rolled out, and in another pair of pieces, Dallas Liddle described why he hates it and Dara Rossman Regaignon why she likes it. Regaignon reminded us that citation is rhetorical, and the new MLA handbook makes strides in helping writers see convention, citation and style as always situated within a rhetorical situation. Conventions always respond to an exigency, and so they prompt questions of just who it is that we are writing for when we compose our Works Cited page.

The new MLA reaches out to two audiences. By simplifying citation to follow the same template whether citing a tweet or a monograph, the eighth edition reaches the uninitiated. It makes citation practices accessible, easy. After teaching the new handbook last year, this seems to me its greatest strength. Students get it.

At the same time, the new MLA reaches out to seasoned scholars. If an article appears in a journal, for example, but I download it from JSTOR, I should also cite the latter. The new conventions support a serious writer deeply invested in citation practices and what they suggest about our disciplines. As ungainly as a URL is, the new handbook wants them included in our citations, and for good measure. Allow me to explain.

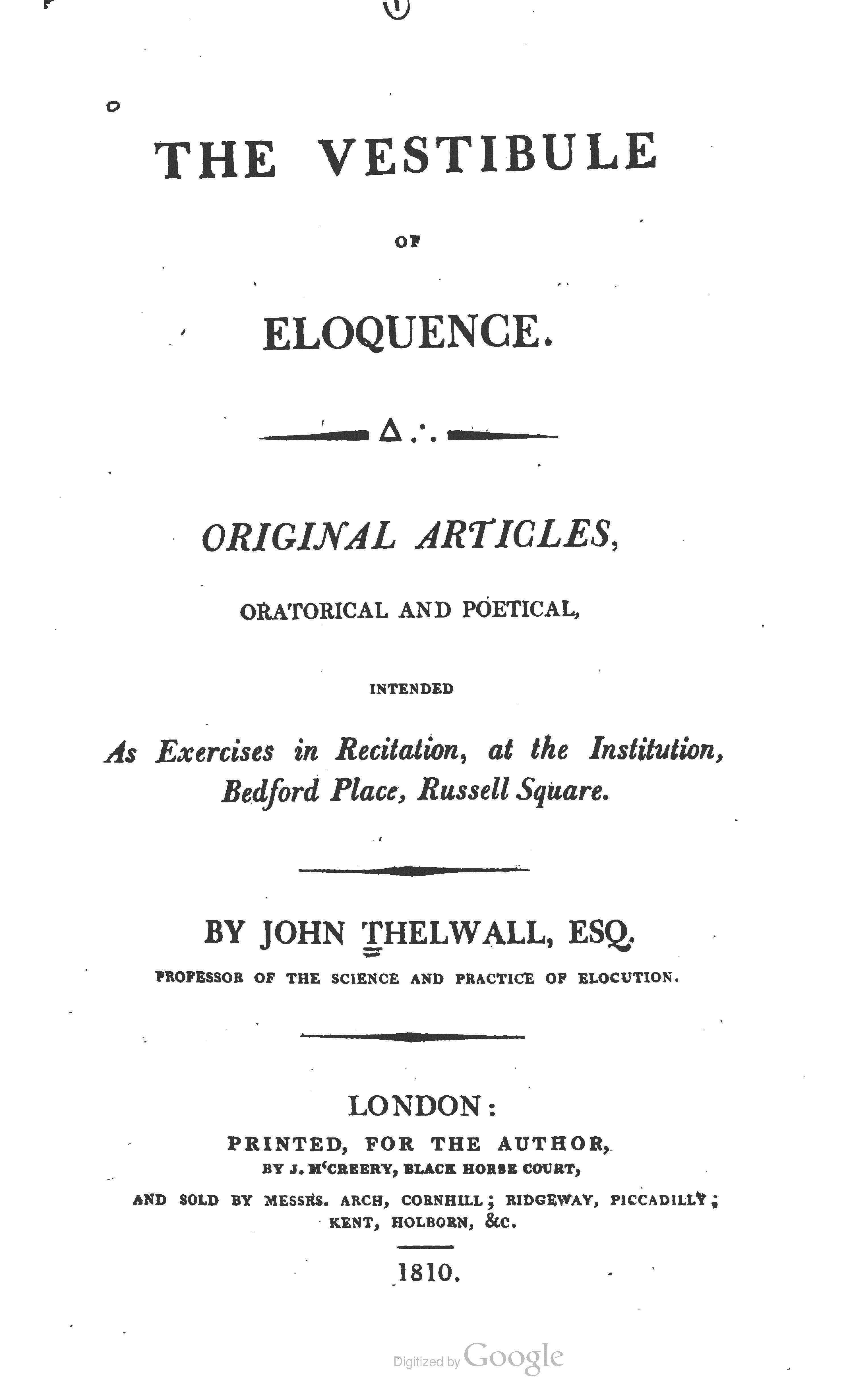

As a graduate student, I wrote a seminar paper on John Thelwall’s 1810 The Vestibule of Eloquence: Original Articles, Oratorical and Poetical, Intended as Exercises in Recitation, at the Institution, Bedford Place, Russell Square. Part of the fun in researching that project was tracking down materials like The Vestibule of Eloquence from Thelwall’s school, as the school and textbook were some of the first specifically for students with speech impediments.

As a graduate student, I wrote a seminar paper on John Thelwall’s 1810 The Vestibule of Eloquence: Original Articles, Oratorical and Poetical, Intended as Exercises in Recitation, at the Institution, Bedford Place, Russell Square. Part of the fun in researching that project was tracking down materials like The Vestibule of Eloquence from Thelwall’s school, as the school and textbook were some of the first specifically for students with speech impediments.

I cite the book following the new MLA:

Thelwall, John. The Vestibule of Eloquence. J. McCreery, 1810. Google Books, books.google.com/books?id=

The new MLA divides this citation into two containers. The first is quite trim, giving author, title, publisher and year. As for the second container, even though we might be tempted to gloss over it -- with its Google Books and unsightly and unwieldy URL -- we shouldn’t. It’s important. It tells a story, a story of circulation. [Editor's Note: This paragraph has been updated to correct the citation.[NOTE]

Rhetorical theorists have been thinking in the past few years about how texts circulate among readers. Jim Ridolfo and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss call it “rhetorical velocity.” It’s the idea that texts get taken up and then are repurposed, reused and recirculated.

This narrative of recirculation is told by the containers within the new MLA citation guidelines. In the Works Cited page, writers account for a source’s circulation: where it was originally found and where the writer found it. That distance from container one to container two tells readers not only where the text has traveled but how the text is being used, reused, appropriated and even rewritten. The Works Cited page, then, becomes archival. It enables readers to trace not only a writer’s reading list, but where and how the writer carried out that research and how those sources make their way through our disciplines.

I look at this citation from another project I’m working on:

Tufte, Virginia, with Garrett Stewart. Grammar as Style. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971.

There’s a story behind this citation and the circulation of Tufte’s book. I recall my emails to Tufte’s former students, my attempts to contact Tufte herself, the PDFs of Grammar as Style I found online and the grant money I used to purchase this $175 out-of-print book after having it checked out from the library for four years. A Works Cited page begins telling that story, but it is a story much larger, much more complicated, much more nuanced, than a single citation could share. And while a citation can hint at this story and the rhetorical velocity of Grammar as Style, there’s no way to cite the process I went through to get Tufte’s book. There are some research stories the academy is inclined to tell on a Works Cited page (for instance, finding an article on JSTOR) but others (like tracking down a rare book) not so much.

So whenever I pick up something to read, I first review the Works Cited page. I’m curious not only who shows up there and where this research sits within the field, but so too I’m curious about what’s happening in that second container -- curious for the insight it gives into how the author went about her work, how those sources are circulating, what institution controls access to them.

And that is why, too, when I respond to student work and revise my own, I go straight to the Works Cited page. I’m concerned when one database dominates the paper. I’m concerned that one institution -- whether JSTOR or Google or EBSCOhost or a publishing house -- can influence our research, however subtly, by determining what texts are read, what texts circulate in our fields, what texts have rhetorical velocity. I’m concerned that knowledge will become centralized, and I look to the Works Cited page to tell that story.

Liddle is right, then, when he says that citation practices reflect the ethos of the discipline, and I would add that this ethos appears not only in our citation conventions but also in the citations themselves and what they tell of how a given discipline carries out its intellectual work. I am worried that I’ve seen some academic publications excising the second container. As the citation is rhetorical, I get it. In the interest of trimming words, given this audience of academics who likely knows where and how to find these sources, the second container might not be necessary. But in cutting it -- and I’ve done it myself, guilty as charged -- we’re erasing a narrative that tells how our fields do research.

This objection, of course, brings us back to rhetoric: What is the purpose of the citation? Is it for first-year writers to gain access to the customs of the academy? Is it to observe how our colleagues research? Is it to provide an archival account of reading practices? Is it to record, somehow, what happened at the writer’s desk? Is it to enable future scholars to carry out projects?

Yes -- to all of the above, and more. And so, while I have my own feelings about the importance of the URL and that second container, these hobbyhorses are secondary to the larger questions any writer must address when sitting down to write: Who is my audience? What is my purpose? And, given that audience and purpose, what do I need this citation to do?

We finally have a handbook that has writers -- both teachers and students -- asking these questions and thinking more critically and more rhetorically about citation than we ever have before.