No Family Is Safe From This Epidemic

As an admiral I helped run the most powerful military on Earth, but I couldn't save my son from the scourge of opioid addiction.

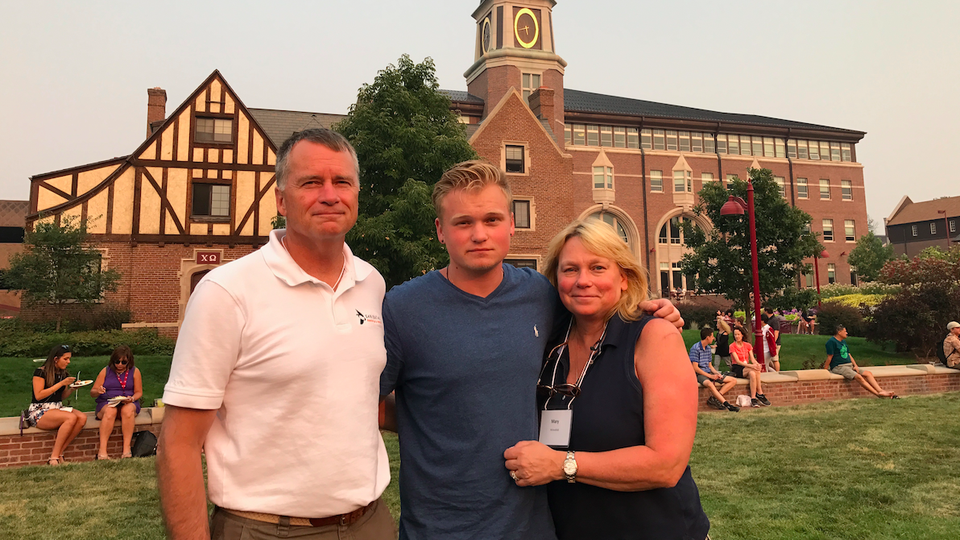

The last photograph of my son Jonathan was taken at the end of a new-student barbecue on the campus green at the University of Denver. It was one of those bittersweet transitional moments. We were feeling the combination of apprehension and optimism that every parent feels when dropping off a kid at college for the first time, which was amplified by the fact that we were coming off a rocky 16 months with our son.

We had moved him into his dormitory room only that morning. I remember how sharp he looked in the outfit he had selected, and his eagerness to start class and make new friends. We were happy, relieved, and, knowing what we thought he had overcome, proud. At lunch, I asked Jonathan whether he thought he was ready for the coming school year. “Dad, I can handle it as long as I continue my recovery,” he said. “Everything flows from that.”

Only three days later, Jonathan was found unresponsive in his dormitory-room bed, one of several victims of a fentanyl-laden batch of heroin that had spread through the Denver area that week.

* * *

Jonathan grew up as the introverted, but creative, younger kid in a career Navy officer’s family. He was born a week after I returned from a long deployment, and lived through two deployments before reaching his fourth birthday. During one six-year stretch, he attended school in five different districts due to military moves. The one constant was his big brother, his best friend, whom he followed around like he was a rock star. I remember him grinning from ear to ear when he was asked to play on his brother’s soccer team because it was short one kid, and again when the two of them learned to ride a bike on the same day.

It wouldn’t be the last time Jonathan proved himself a quick study. When Jonathan was in the second grade, his teacher called to notify us that he was selling school supplies to his classmates, lending them money with interest. In the fifth grade, he made a perfect score on the Virginia Standards of Learning science test. In the ninth grade, he hit a walk-off single in a baseball tournament. A year later, he pitched seven gritty innings of no-hit ball over two consecutive all-star games, with the help of a curveball that seemed to defy gravity.

Jonathan was quiet, but he had a big heart. He helped coach little kids in baseball and laid wreaths at Arlington National Cemetery. He had no enemies, only friends. His baseball coach told us his mind was a gift. “He was a brilliant kid who never laughed out loud that I can remember, but he had a wry and knowing smile,” he told me. And Jonathan was humble, only replying “thank you” when complimented, never letting anything go to his head. “Jon didn’t brag about what he knew or who he knew,” his coach said.

Jonathan’s military lineage extended to a grandfather and great-grandfather who also served in the Navy, and a great-great-grandfather who was a Prussian cavalryman. One of the few times I saw Jonathan beam with genuine pride was when he was given his great-great-grandfather’s sword at my retirement ceremony. The moment was deeply meaningful to him because it signaled equal recognition among family; Jonathan had to pedal hard in the shadow of a successful father and a brother now carrying on the tradition of military service.

On the surface, Jonathan was a handsome, shy, gentle kid with a warm and disarming demeanor. But underneath that exterior he struggled with anxiety and depression, which eventually spiraled into addiction, with all its sickening complexity.

* * *

Many people have a simple understanding of addiction. They think it happens only to dysfunctional people from dysfunctional families, or to hopeless people living on the street. But our addicted population is spread across every segment of society: rich and poor, white and black, male and female, old and young.

There are several gateways to opioid addiction. Some people suffer a physical injury, and slowly develop a dependency on prescribed painkillers. Others self-medicate for mental ailments using whatever substance is available. Because the brain is so adaptable while it’s still developing, it’s highly susceptible to dependencies, even from non-opioids such as today’s newly potent marijuana strains. We now understand that early marijuana use not only inhibits brain development; it prepares the brain to be receptive to opioids. Of course, like opioids, marijuana has important medical applications, and it seems to leave less of a mark on a fully matured brain. It’s worth examining whether it would make sense to raise the legal marijuana age to 25, when the brain has fully matured.

From an early age, Jonathan lacked confidence and self-esteem. He never seemed comfortable in his own skin. He followed more than he led. Like many of the 40 percent or more of teenagers who have reportedly suffered from one mental-health issue or another, Jonathan started on the road to addiction early. He began by sneaking a bit of alcohol at night in order to bring himself down from the Adderall a doctor had prescribed him, based on a misdiagnosis of attention deficit disorder. By the eighth grade, he was consuming alcohol in larger quantities and beginning to self-medicate with marijuana. Next came Xanax and, eventually, heroin.

We first tried counseling and psychiatry for Jonathan, thinking this was merely a matter of bad friends and worse choices. We figured that he would age out of it and turn away from drugs. Not understanding how addiction progresses, we foolishly hoped, reinforced by his assurances, that every incident would be the last. The incidents worsened after a girlfriend turned away from him and he was disqualified from playing varsity baseball during his senior year due to deteriorating grades. One April night that year, a suicidal gesture and a car accident left him in the hospital and left us with no doubt that we needed to make a radical change.

With no available spaces in treatment facilities in Washington, D.C., Jonathan detoxed in Richmond, Virginia, for a week while we frantically searched for an inpatient center that would accommodate his dual diagnosis of depression/anxiety and addiction. He growled that putting him into treatment was the worst mistake we would ever make. But we stuck with our decision, and sent him away to two sequential state-of-the-art inpatient treatment programs.

According to the treatment professionals with whom we worked, it takes most addicts well over a year of skilled, intense inpatient treatment to even have a chance of recovery, and my son is evidence that not even that amount of time is a guarantee. Effective treatment generally requires a combination of craving-reducing drugs (to give recovery a chance), time (for the brain to literally recover), counseling (for the addict to understand what he or she is going through), mutual support (to maintain sobriety), and transition training (to prepare for reentering society).

Even getting people into treatment can be difficult, although some are trying to make doing so easier. In drug courts, for instance, judges are able to suspend drug-offense sentences in favor of an addict entering—and remaining in—a treatment program. But these programs are still terribly expensive. Because the military’s Tricare medical system would not adequately cover treatment for a dual diagnosis, we dug in and spent more than the equivalent of four years’ tuition at a private college for 15 months of treatment for Jonathan, a sum that would be well beyond the reach of most American families.

It wasn’t until our exposure to the parent-education sessions at Jonathan’s first treatment center that we awakened to the full horror of addiction’s relentless spiral. Unlike cancer, which can be seen under a microscope, addiction works away at the brain much more covertly, using the brain’s own flexibility against it.

As Sam Quinones writes in his book Dreamland, the morphine molecule has “evolved somehow to fit, key in lock, into the receptors that all mammals, especially humans, have in their brains and spines ... creating a far more intense euphoria than anything we come by internally.” It creates a higher tolerance with use, and, Quinones continues, exacts “a mighty vengeance when a human dares to stop using it.” What starts as relief of physical or mental pain transforms into a desperate need to avoid withdrawal.

Treatment was tedious for Jonathan, due to long periods of boredom and his discomfort at being required to reach out to others and talk about himself. But he knew he needed help to recover. Over 16 long months, we saw him almost miraculously begin to pull out of the abyss. We were gradually getting our son back. We watched as his brain recovered and he turned back into his old self. He was more communicative, he was happy to see us when we visited, and he even led a 12-step Alcoholics Anonymous meeting once a week.

In his last few months in treatment, Jonathan sought and earned his emergency-medical-technician qualification. He said he wanted to use it to help others, especially young people, avoid his experience. He was so proud that he had found something he loved to do. It was one of the very few things that would light him up in a discussion, so we brought it up with him whenever we could.

Based on his steady progress in recovery, and his successful completion of the rigorous EMT certification program, we thought Jonathan was ready to reenter normal life, and we believed that he deserved the chance. Together, we decided he would attend the University of Denver, which had granted him a gap year after high school. Thanks in part to a sympathetic admissions counselor who had an experience with addiction in her own family, the school agreed to allow him to enter in the fall.

The members of his incoming class were required to read J. D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy over the summer and to write an essay about a person who had had a profound impact upon their life. Jonathan wrote powerfully about encountering a man in the grip of an overdose-induced cardiac arrest in a McDonald’s bathroom during the first ride-along of his EMT training. He said the experience had made him realize how precious life is. “I never found out his name,” he wrote, but the experience had made him see his life “in a whole new light.”

Sadly, the morphine molecule had burrowed deeper into his brain than we understood. Even as he was writing his moving essay, referring to himself as a former addict, his relapse was already one week old. Such is the Jekyll-and-Hyde nature of the disease of addiction.

During the weekend before we dropped off Jonathan at college, we missed the telltale signs of relapse. Feeling the shame of his condition, Jonathan used the addicted person’s shrewdness to hide them. As for us, we were blinded by our own optimism. We read his restlessness as an understandable case of nerves about what was coming next, or perhaps too high a dosage of anxiety medicine. In retrospect, it appears that he was experiencing symptoms of withdrawal.

* * *

Scientists who study addiction understand how little the disease needs to return at full strength. Even brief flashing images of drug paraphernalia are sufficient to trigger a flood of dopamine in a recovering brain, which can, in turn, cause a relapse. The addict is all the more vulnerable when access to the drug is easy. The location where Jonathan, two weeks away from entering the University of Denver, was taking a nighttime electrocardiogram course is close to one of that city’s open-air heroin markets. He told one of his friends back home that he had been offered heroin while walking back to where he was staying, but had refused. This encounter likely provided the stimulus for his relapse and eventual overdose.

Instead of allowing these open-air markets to thrive, we would do well to develop “safe-use zones” like those in Portugal and parts of British Columbia. These areas not only dramatically reduce opioid overdoses (because trained users of the overdose-reversing drug naloxone can be right on the scene); they can offer treatment to addicts who are ready to seek help.

We are hopeful that the exceptional efforts of a determined Denver police detective will lead to the apprehension, prosecution, and punishment of the drug dealer who sold our son that fatal fentanyl-laced dose. Indeed, the deadliest link in the overdose supply chain is the street dealer who looks an addicted person coldly in the eye and sells what he or she knows could be the person’s last high. However, much of our prosecutorial apparatus views selling drugs as a “nonviolent crime.” Many refuse to prosecute for the small amounts that dealers carry. Some dealers are released overnight, allowing them to move on to another location to resume their deadly work.

Meanwhile, addicts continue to suffer under long-standing stigmas associated with drug use, and are subject to the same punishments as dealers. Data from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Program show that of the approximately 1.2 million people arrested for a drug-related offense in 2016, 85 percent were arrested for individual drug possession, not for the sale or manufacture of a drug. This is no way to solve an epidemic.

* * *

Drug overdose, like the one that took Jonathan from us, is now the leading cause of death for Americans younger than 50 years old. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that more than 64,000 Americans lost their life to a drug overdose in 2016, including 15,446 heroin overdoses. The total is more than 20 times the number of Americans killed on 9/11.

The costs of the opioid epidemic—in terms of health care, its corrosive effects on our economic productivity, and other impacts on society—extend far beyond the loss of life. The White House Council of Economic Advisers just raised its estimate of the epidemic’s annual cost from $78.5 billion to a whopping $504 billion. Princeton University’s Alan Krueger recently completed a study suggesting that 20 percent of the reduction in male participation in our workforce is due to opioid use, and that nearly one-third of prime-working-age men who are not in the labor force are taking prescription pain medication on a daily basis. I sit on the board of a medium-size industrial company in America’s heartland that has had trouble recruiting employees, despite being willing to hire anyone who walks in the door who can pass a drug test.

If America is going to reverse this epidemic, we need to start treating it like the national emergency it really is. We need a call to arms like the one that led to our nation’s dramatic decrease in cigarette usage, or to the effective Mothers Against Drunk Driving movement. There are reasons to hope that public awareness of the opioid epidemic is finally beginning to catch up with the facts on the ground, but its defeat will be possible only through a concerted effort that includes full-spectrum prevention, stronger prescription-drug controls, more-robust law enforcement, and far more access to quality treatment. All of this will in turn require major increases in public resources.

The final sentence of Jonathan’s University of Denver freshman essay reads, “I now live my life with a newfound purpose: wanting to help those who cannot help themselves.” Jonathan was very serious about his recovery. He wanted to live, and was on an upward trajectory, with brand-new hopes and dreams. He fought honorably against the demons of this disease, but, as with so many others, he lost his battle. Losing Jonathan has left us heartbroken, but we are determined to carry his purpose forward. If his story leads to one less heartbroken family, it will have been worth sharing.