Dirk Aaron’s timing was terrible. He took over management of Bell County’s Clearwater Underground Water Conservation District in the summer of 2011, which the National Weather Service regards as the driest year in Texas history. What made the drought particularly difficult was that the less it rained, the more groundwater people pumped. When Mother Nature isn’t watering your yard or your farm, you have to do it yourself. That dynamic played hell with the resources Aaron had been hired to watch over in this neck of Central Texas, about fifty miles north of Austin. Water levels in the Trinity Aquifer, the county’s main source of groundwater, plunged. He got the county through the crisis, and thanks to some heavy rains in 2012, the aquifer rebounded a little. But the Trinity never fully recovered.

In the Panhandle, where Aaron had worked as an agent for the Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service, he’d seen firsthand what happens when people pump aquifers like there’s no end to them. But in places like Bexar County, whose seat is San Antonio, he’d collaborated with South Plains farmers to foster efficient irrigation practices and had seen how groundwater can be managed with tomorrow in mind.

That’s what Aaron is endeavoring to do for his home county. He was a military brat who grew up near Fort Hood and then on a ranch in Stillman Valley, in Bell County’s southwest corner. He put himself through college by working on farms and ranches, hauling coastal hay, and clerking in feed stores. He feels a kinship with the country people on whose behalf he now works as well as a responsibility to protect the aquifer that makes their way of life possible.

Now middle-aged, with a bare and shining scalp, Aaron brings to the county’s conservation district a kind of duty-bound, Boy Scout earnestness. As its first-ever general manager, he’s in charge of prolonging the lives of the local aquifers. While state law still invests landowners with the right to the water beneath them, it provides the district with a regulatory lane, albeit a narrow one, in which to maneuver. Aaron and the district’s board can, for instance, insist on certain spacing requirements between wells and enforce limits on groundwater usage. Using those powers, he has set about making the district a model for water management, an entity that collects a small yearly property tax ($3.83 on a house worth $100,000) and spends the money on tasks like generating three-dimensional models of the area’s subsurface. If you plan on sinking a well in Bell County, Aaron can tell you how deep you’ll have to dig before you hit water.

These days, though, in the southern part of his district, he can also tell you where you’ll find less and less of it. That’s the part he didn’t foresee when he took the job. In 2014 the monitoring wells that surveil his domain started hinting at a crisis. There were troubling reports, too, from well owners and drillers who had to lower their pumps to chase after declining water levels. Then, last summer, when the dry times started creeping back, the Trinity nose-dived. Record rains eventually followed. But this time, the aquifer didn’t rebound at all. Aaron was forced to confront the possibility that the resource that had provided water for the area since long before he was born might disappear in his lifetime. He couldn’t help but feel as if he had failed the district’s anxious constituents, who kept asking him, “How much water do I have left?”

The news he had to deliver was brutal. In some cases, it looked as if homeowners, farmers, and ranchers had only a few years’ worth of water left. Sometimes it was less than that. And these weren’t just people worrying about the value of a future sale or looking to subdivide. These were landowners who had no interest in pulling up stakes. Some lived on a fixed income, unable to afford even the $3,500 or so it would cost to lower a pump below water level.

What left an especially bitter taste in Aaron’s mouth was that these people hadn’t done anything wrong. Water usage in his county couldn’t account for the decline. Something else—someone else—was sucking the water right out from under his district.

To see how this could happen, it’s important to understand that in Texas, there are two kinds of water. There’s surface water, the stuff that flows through rivers and gets dammed up in reservoirs. All of that is allocated down to the acre-foot with mind-boggling precision to cities, special utility districts, and wholesale suppliers. Then there’s the water that’s underground. Products not of engineering but of rainfall that has collected in sand and limestone formations over millennia, aquifers supply approximately 60 percent of the water used in Texas. About 75 percent of that is for agriculture, with the rest split between industrial and domestic uses. Nearly a fifth of the state’s drinking water is pumped from the ground. Yet the consumption of groundwater is regulated with less vigor and uniformity than the pumping of Permian oil.

Back in the late forties, Texas began its descent into a drought that would touch off a frenzy of dam and reservoir construction to establish the state’s surface-water supplies for the next century. At the same time, municipalities and regulators were learning the hard way that groundwater was not only exhaustible but nearing exhaustion in some parts of the state. Politically powerful Lubbock irrigators had for decades successfully opposed legislation to regulate aquifers, but they could see change coming at them as clearly as an approaching dust storm. They could either resist and get steamrolled by bureaucrats in Austin, or they could mold legislation that looked like a compromise.

The result was a 1949 bill that tackled groundwater regulation piecemeal, with a county-by-county system of oversight through groundwater conservation districts. The districts would, in large part, be left to do as much or as little as state law allows. In some respects, this made sense: every county has different needs and overlies different crannies of wildly complex aquifer systems.

The rub was that each of these small jurisdictions would have little ability to address an issue just beyond the county line, even if the district was profoundly affected by its neighbor’s actions. And not all districts would be equally engaged. Some would choose to be extremely active; others would turn out to be mere shells created to head off state regulators. In fact, district formation itself would remain mostly optional. Unless compelled by the state—which has happened rarely—counties could opt out of groundwater management altogether. Of the state’s 254 counties, 74 have opted out, and that doesn’t include the counties that are only partly encompassed by a conservation district’s jurisdiction. That leaves more than a quarter of the state without any groundwater regulatory body.

The 1949 legislation was a coup for farming interests. Said Southwestern Crop and Stock magazine at the time, “West Texans can consider the water their own—to use or waste as they please.”

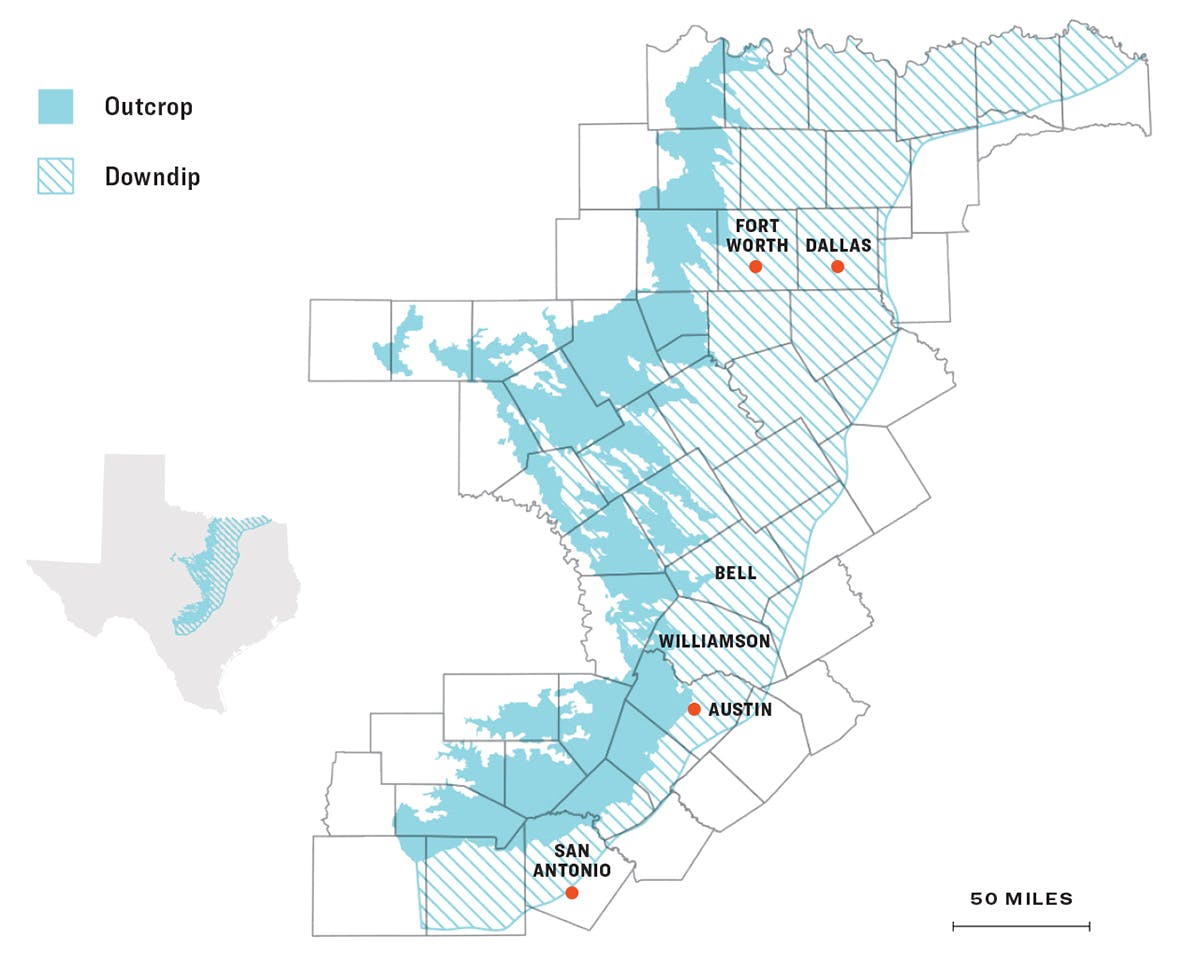

The Trinity Aquifer

The aquifer stretches from North Texas to South Texas and has two main components: the outcrop, which is close to the surface and which is where the water enters the aquifer, and the downdip, which is the part of the aquifer that’s deep underground. Most people in Bell and Williamson counties get their water from the downdip.

Last September, at Bell County’s Clearwater headquarters, a small brick building set out in a clearing surrounded by stately post oaks not far from I-35 in Belton, Aaron fired up the projector in a conference room to show me just where his water had gone and where it was still going.

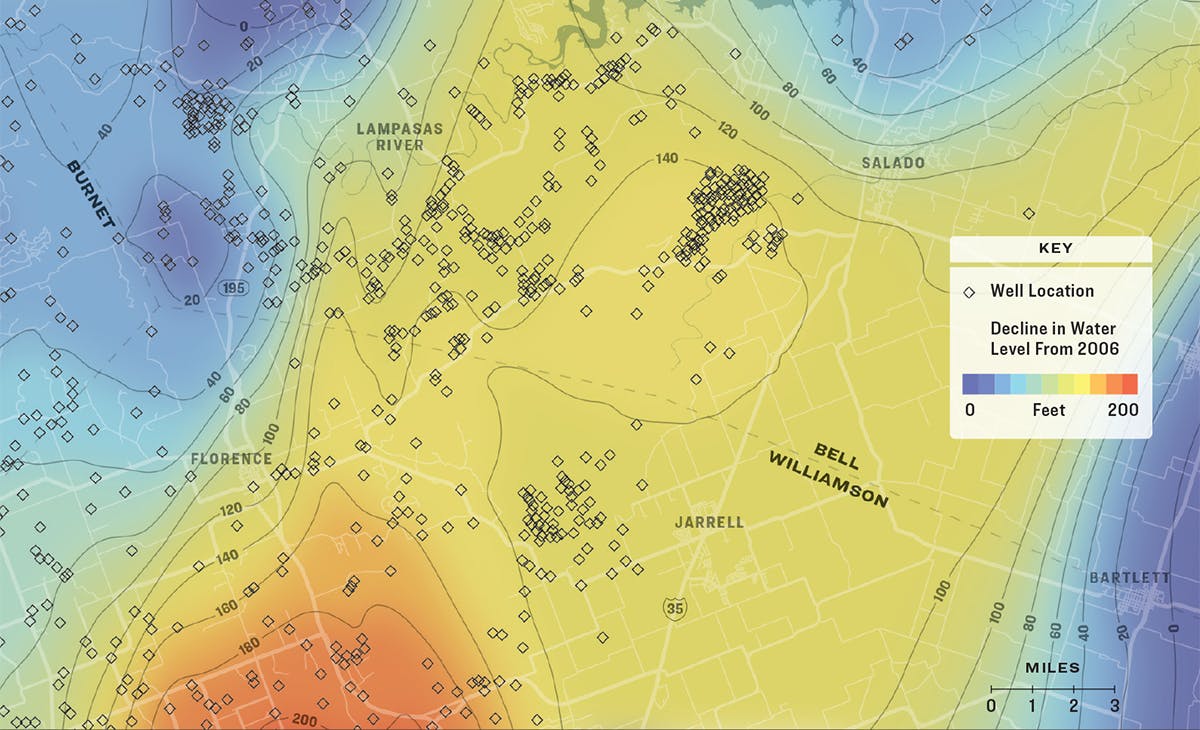

In 2014, he explained, the district hired Mike Keester, a geoscientist and groundwater expert, to look at what was happening to the stretch of the Trinity that lies beneath the northwest corner of Williamson County and the southwest corner of Bell. What he wanted was proof of water-level decline spreading like rot from Williamson into his jurisdiction.

Mapping the change in water levels year by year was easy enough to do in Aaron’s district. “We can get right down to the exact amount of water pumped from each layer of the Trinity Aquifer on an annual basis,” he said with a touch of pride. But getting an idea of what was going on to the south would require some heavy lifting. Williamson doesn’t have a groundwater district, meaning no one had been watching its aquifers closely. It was Keester’s job to plot hundreds of Williamson County wells and orient their water levels in time and space to tell the story of the shifting seas hundreds of feet beneath the surface.

What Keester reported in 2015 confirmed Aaron’s fears. Wells throughout both counties had been pumped so much that they would soon lose nearly all pressure. The explanation for this was apparent to Aaron: within the past decade, breakneck development had crept up I-35 from Austin, Round Rock, and Georgetown into the rural northwest quarter of Williamson County, availing itself of the cheap and relatively abundant water provided by the Trinity Aquifer. The newcomers had not only drained the ground beneath their own feet but had created a vacuum in the aquifer that was draining Bell County’s water supply as well. Last summer, Keester updated his analysis. In the three years since his 2015 report, the aquifer declines in both counties had gotten worse.

The contour map Aaron projected onto the screen for me looked topographical, with parallel and swirling lines laid over shades of yellow and blue, pink and red. Near the bottom of the map, in northwestern Williamson County, was a red blob. “We have two hundred feet of decline right here,” he said. That means that over the past twelve years, water had retreated two hundred feet down wells in that location in Williamson, leaving as little as ten feet of water in some places. Aaron gestured to the north, into his district. “[The blob] is sucking water from this direction”—sparsely populated southwestern Bell—“and into this direction”—northwestern Williamson.

The drawdown is bound to intensify because, unlike the nearby Edwards Aquifer, the Trinity isn’t fed by karst fractures, rock cavities that make it easy for rainwater to feed an aquifer. Instead, it’s recharged way out west, around Lampasas and Burnet counties. And from there, the water creeps ever so slowly toward Williamson and Bell through tightly packed belts of sand.

When a well sucks water out of an aquifer faster than it can be replenished, it creates a pocket of sand no longer saturated by water, a phenomenon known as a cone of depression. Under conditions of normal rainfall and sustainable pumping, things should level back out as the aquifer replenishes the cone. But when you’ve got a place developing as rapidly as Williamson County—the 2010 census pegged its population at 422,679; county officials believe it has since hit 600,000—the cones of depression start to intersect. Each well drains the next, a kind of mutually assured depletion. The trend might stall out when people stop watering their lawns during the winter, but the area’s overall water level will likely keep declining year after year. “If we continue this trend, the water becomes unconfined,” Aaron said, meaning its level drops so low that it is no higher than the part of the well that lets the water pour in. Once that happens, “then there’s no longer any pressure. [The water is] just dribbling in.”

As badly as this has hurt Bell County, Aaron’s maps seem to indicate that the northern part of Williamson County is just as much a victim. Florence, a small Williamson County town at the northern edge of the blob, gets most of its municipal supply from the Trinity. After one of its three wells hit bottom in 2011, the town considered drilling another. “We were advised not to do it,” said Mayor Mary Condon. “We were sitting on a cone of depression, and [the civil engineers] didn’t think it would work.” Florence was able to obtain the rights to five hundred acre-feet of surface water from the Brazos River Authority to make up the difference, but more will be hard to come by; most of the reservoir capacity in the area is already spoken for, and there’s little prospect of building any new ones.

Water levels in the Trinity have declined by one hundred feet around the town’s municipal wells over the past twelve years. Keester’s analysis indicates there are only one hundred feet left to pull from. With the drawdown of the aquifer accelerating, it won’t take another twelve years for the wells to become unconfined. Said Condon, “I’m a water worrier.”

My parents rely on a well in Williamson County that lies within or very near that big red blob on Aaron’s map. Last summer, the tap above their kitchen sink suddenly stopped running. “That is a bad, bad feeling,” my dad said, “when you’re on a water well and you don’t have a water line as backup.” Going dry wasn’t something he’d ever thought to worry about. Back in 1999, when he’d had the well put in, he asked the driller if the aquifer was deep enough to last. He still remembers the answer. “That water table is really deep,” the driller assured him. “You’ll never run out.”

On a recent afternoon, I took a drive to see firsthand what lay at the center of Williamson County’s cone of depression. It’s a piece of Hill Country that I know well, or at least I thought I did. Driving down from Dallas, I left I-35 and headed west on Ronald Reagan Boulevard, which snakes across the gentle swell and fall of hills shaggy with grama and wooded by dense stands of cedar and live oak.

But that’s not all you’ll find there. Sun City, an age-restricted development that was founded in 1994, is growing north into what was once rangeland. The community of 12,000 people boasts no fewer than three golf courses (which may be partly irrigated by gray water), their attendant ponds and fountains, a fishing hole, and at least eleven irrigation wells, all drilled since 2010. As I drove by, backhoes toiled in the bar ditch, cutting a sewer-line trench for the expansion. Directly across the road was a sand and gravel quarry. As I drove farther west, I could see the mammoth hummocks of overburden rising above the low tree canopy, indicating the presence of open-pit asphalt and limestone quarries just below.

I’d spent much of my childhood east of here, in the flat farm country near Weir, on the other side of I-35. When my dad, a welder by trade, started building our new house in northwestern Williamson County, we moved temporarily to Georgetown. When the new place was ready, I was exasperated. Then a high schooler, I’d gotten used to city living and the ease with which I could meet up with friends. I was reluctant to return to another spare backwoods more than fifteen minutes from town.

Two decades later, to my astonishment, the backwoods have become the exurbs seemingly overnight. There are still grazing pastures lining the roads, but the fences are hung with signs that read “Will subdivide.” These are alongside tony new exurban developments with ornate stone entranceways advertising “ranch life” on “1-acre sites.”

When I consulted the “historical imagery” function in Google Earth and toggled between satellite snapshots from the early nineties to 2016, I could watch the quarries sprout and expand, pale, scoured pits against the dark-green woods, supplying the raw materials for the roads and housing developments marching north out of Georgetown. Those quarries spray lots of well water to keep the dust down and to wash dirt off the gravel they use to make asphalt. The new developments more often than not have dug irrigation wells to keep the landscaping green and the ponds full. Growth has arrived, and it’s thirsty.

If the quarry wells hit bottom, the owners can afford to dig deeper wells, at least until their mining permits expire. The people who are getting crushed against the approaching bottleneck are the people in rural northwestern Williamson and southern Bell counties—people like my parents. In August my parents had their pump lowered another sixty feet, and they can once again access water. But there’s no telling how long that will last.

If you drive north from Williamson County into Bell County, you see land that looks like the growing parts of northwest Williamson did 25 years ago. There are ranch houses and double-wides with small herds of Spanish goats out front and cattle grazing on buffalo grass. One recent evening I drove up county roads winding around steep limestone bluffs, then pulled off onto a washed-out dirt road near Youngsport.

Just off the road, in dense cedar brush, Scott Brooks was standing in front of a single-story contemporary home painted a mustard cream. Wearing a pair of small, oval wire-framed glasses and sporting a handlebar mustache that drooped past his jowls, he looked like those old tintypes of a glowering Wyatt Earp. A decade ago, when he and his wife, Stefanie, bumped up the hill through the cedar woods to scout the place out and laid eyes on this little clearing, they knew instantly they’d arrived.

Brooks, a civil engineer whose voice betrays the hard vowels of his native Wisconsin, is the self-sufficient type. He likes the idea of rural isolation, of pulling his water from the ground beneath his feet, not from some municipal utility and a reservoir miles away. But four years after his well was drilled, the 2011 drought hit. One day in 2012, Stefanie turned on the tap and nothing came out. Their pump had sucked air and burned up. The water level had been 567 feet below the surface when the well was sunk. It now sat at 655, a decline of 88 feet in just five years. Brooks hired a local driller to lower his pump beneath the new water level, but the aquifer has continued to retreat.

He started attending meetings in the Clearwater district to get a better handle on the problem. When a groundwater district board seat opened up, he ran for it and won. Brooks has a small-government, libertarian streak. He works for a land-development company, assessing water and sewer infrastructure. “I don’t like regulations,” he said, “but this is one of those situations where it’s the role of government to protect us. We have a big body of water underneath us, and unless we share it, we’ll run out.”

I found people like Brooks all over the area. There’s even a Facebook group for landowners whose wells are plummeting or played out. To the southwest, near the Burnet County line, Joe Rizzo’s well went dry last year. He ran a garden hose to his neighbor’s tap for four months until he shelled out $12,000 for a new well. Near Florence, in Williamson County, landowner David Gola has seen his well lose sixty feet of water in six years. It isn’t any big mystery where his water is going. Across the street from his place, he can see an asphalt quarry’s three-acre pond. At night, he can hear the pumps running.

The Texas Commission on Environmental Quality and the Texas Water Development Board knew that growth was coming to the counties north of Austin but assumed that everyone would switch from aquifers and start drawing water from surface sources such as Lake Georgetown, Stillhouse Hollow, and Lake Belton. And to a certain extent, that has happened. Round Rock, in south Williamson, is one of the fastest-growing cities in the country, and it relies almost entirely on reservoirs. Georgetown, in central Williamson, does the same. Even in some of the big new developments in northwest Williamson, the homes are valuable enough that the developer can afford to extend the infrastructure to meet Georgetown’s water lines. That’s the city’s answer for people in the Trinity decline: more surface water. “We try to accommodate them when we can,” said Jim Briggs, the general manager of Georgetown utilities.

But not every development or rural landowner can afford that. When the lines aren’t close, accommodation gets expensive. Cecil Jenkins, a retired real estate agent near Florence, says he paid $20,000 to get city water—even after his son dug the trench for the line free of charge. Joe Rizzo tried to get onto a Georgetown line but was told it was oversubscribed. Brooks says he’d have to install four miles of pipe and obtain numerous easements in order to reach the municipal line. “We don’t have any other supply of water for those people,” said Williamson County commissioner Terry Cook. “For the short term, wells are the only answer.”

Given the state of groundwater, that’s not much of an answer. Until denser development brings the water lines into rural northwestern Williamson County and southern Bell, it’ll be every man and woman for themselves. Some will install rainwater catchment systems, like my dad is planning to build (one driller I spoke to is already considering diversifying into this emerging growth market). Others will have no choice but to drastically depart from the domestic habits to which modern Americans have become accustomed—or move somewhere else.

The only sure scenario seems to be the Trinity’s fall, because the sole entity empowered by state law to stop it would be the groundwater conservation district that Williamson doesn’t have. And no official I spoke to seems keen on the idea of setting one up in what has been a regulation-averse, anti-tax Shangri-la north of Austin. Any legislative effort to do so would meet the likely opposition of state senator Charles Schwertner, of Georgetown, a city that doesn’t depend heavily on groundwater and where the idea of levying even a nominal tax to tackle a problem that doesn’t affect its residents—at least not yet—is politically unpalatable. The outlook is the same at the county level. “I don’t think our constituents would want that,” said Williamson commissioner Valerie Covey.

Developers, too, have a stake in keeping a groundwater district out of Williamson County. The make-or-break component of any potential new housing development is the water supply. “One of the first choices for some of the developments out there is to look at whether they can serve their residents with groundwater rather than the more expensive option of going with Georgetown,” said Aaron’s hydrogeologist, Mike Keester, who has plenty of commercial customers. But if an aggressive district were put in charge of the beleaguered Trinity in Williamson, developers would be forced to take their neighbors into consideration. The district might set strict limits on how much water could be drawn from the aquifer, which could mean the developers would have to spring for city water or scrap the subdivision altogether. But right now, whether the Trinity will be a productive aquifer fifty years down the road is not a question with which builders need concern themselves. In the end, it’ll be someone else’s problem.

When it comes to groundwater in Williamson County, it’s always someone else’s problem—usually the rural homeowners and landowners. If that’s going to change, it’ll have to happen at the insistence of the Legislature, a few miles down the highway, in Austin. That’s why Aaron commissioned that hydrogeological map in the first place. It wasn’t for his own edification. He did it to convince the state that it had been wrong about the Trinity all along. He was trying to get Texas regulators and lawmakers to take a second look at what’s happening out here.

Just Subtract Water

The Middle Trinity Aquifer—the part of the aquifer that underlies much of the Hill Country—has recently undergone dramatic declines, thanks partly to low rainfall but mostly to water demands brought on by development.

By 2070, about 20 million more people will live in Texas. That will nearly double the current water demands in a state where, says Bruce McCarl, a professor of agricultural economics at Texas A&M University, drought is expected to reduce inflows into rivers, reservoirs, and aquifers and high temperatures and high evaporation rates will reduce surface sources. Rainy days will become fewer in number and concentrate in prodigious flooding events. “You’ll get some recharge out of it,” McCarl said, “but the dry days will outweigh the flood days, and the water on flood days will head for the Gulf. We’ll see as much change in climate in the next 25 years as we’ve seen in the last 150.”

Another drought of 1950s magnitude is virtually assured, and if it were to strike next year, Texas Water Development Board data indicates Williamson County wouldn’t have enough groundwater or surface water to slake the thirst of progress. In the regional group that includes 37 counties stretching northwest from Brenham to Knox County, “the largest single black hole is Williamson County,” said former Bell County commissioner Tim Brown.

The further one looks ahead, the worse the overall picture appears. Only one of Texas’s sixteen regional water-planning groups has identified the supplies capable of meeting the demand in 2070, and almost none of them have set up region-wide drought-management strategies to cope with the next dry stretch.

Yet despite this bleak prognosis, state officials haven’t focused on our water needs. At a recent gathering of water district managers, Representative Lyle Larson, a San Antonio Republican who chairs the House Natural Resources Committee, noted that the governor and other state officials “don’t talk about it until it’s too late.” Of course, to prepare for the climate of the future, Texas would have to acknowledge that it’s changing in the first place. Yet the words “climate change” don’t appear in the main volume of the 2017 State Water Plan.

There are some signs of movement, though. In January the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, drawing on information gathered by the Texas Water Development Board, released an assessment on the drawdown in Williamson County, and it was pretty grim. One measure the state places great weight on is something called “desired future conditions.” That sounds like a good thing, but it includes such goals as the maximum acceptable decline of water levels in the aquifer. “Desired” here refers not to what we’d ideally want but what we can tolerate if we absolutely have to. And, for the first time, the state acknowledged that in the Trinity, this barely acceptable scenario would arrive not in 2070 but decades earlier—including, in some areas, right now. It was a shocking admission.

“Normally, a groundwater district would have the ability to take measures to mitigate [such] conditions,” said Larry French, the director of the TWDB’s groundwater division. “But in Williamson County, there’s no district to do that.”

The irony here is that Bell County does have a district to do that, but its hands are tied by Williamson County. “We simply can’t meet the expectations of our constituents in this county,” Aaron said. “Our constitution and the requirement of state law is to protect our natural resources. But the preferred method is not working if everyone’s not playing under the same rules.”

So what happens now? That’s for someone else to decide, French said. TWDB just does the science. The TCEQ has the power to force the creation of a groundwater district in Williamson, but so far it has given no indication it plans to do so. That leaves it to the Legislature.

Just weeks after the TCEQ report was released, Representative Hugh Shine, a Bell County Republican, introduced a bill that would mandate a study of groundwater availability in Williamson and northern Travis counties. “The last thing we need is for our communities to have restrictions on development because we don’t have water,” Shine said.

The outcome he’s aiming for is nothing less than a groundwater conservation district in every Texas county. Asked how such legislation would fare against the opposition of politicians in Williamson such as Senator Schwertner, who has declined to say whether he’d support the bill, Shine brushed the question aside. “He’s one of thirty-one [senators],” he said. “There’s a lot that’s happened in the last twenty years, especially in the Edwards and Trinity aquifers. It’s impacting Bastrop, Bell, Burnet, Lee, Milam, Travis, and Williamson counties. I think there’s gonna be a dialogue to persuade those who may not be supportive.”

The bill has been referred to the Natural Resources Committee, where Shine says Larson has been encouraging. But Shine wouldn’t speculate on how this would all play out. After all, he said, it’s the Texas House. Who knows?

I thought Aaron would be thrilled by the news; someone in the Legislature had heard his pleas and taken up his cause. He wants to be excited, but long experience has jaded him. He fears that, at the insistence of his more populous, more influential southern neighbor, the bill will languish. “This story is a story of the urban divide from rural Texas,” Aaron said. “Folks will see that rural interests always lose out.”

Dallas journalist Brantley Hargrove is the author of The Man Who Caught the Storm: The Life of Legendary Tornado Chaser Tim Samaras.

This article originally appeared in the April 2019 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Goodbye to an Aquifer.” Subscribe today.