The heroin epidemic that has been taking the lives of teenagers for years is creeping into even younger age groups and putting pressure on the nation’s schools to keep a fast-acting overdose antidote within reach of every nurse and teacher.

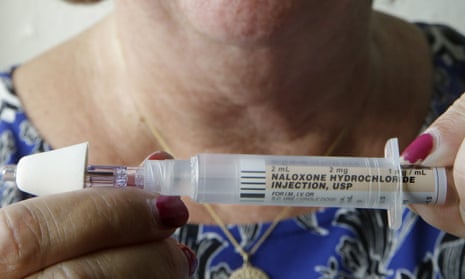

Although overdoses at school are rare, nurses are increasingly thinking of the drug naloxone as an essential part of their first-aid kits. Administered via syringe or a nasal spray, it works almost immediately to get an overdose patient breathing again, and it does not create a high or have major side effects.

The National Association of School Nurses wants all schools to keep the antidote on hand.

“We’re facing an epidemic,” said Beth Mattey, president of the group. “People are dying from drug overdoses, opioid drug overdoses. We need to be able to address the emergency.”

At least five states this year adopted laws on the use of naloxone in schools, including Rhode Island, which now requires it to be available in all middle, junior high and high schools. Some states allow or encourage schools to buy it. And many schools already have the drug in stock.

Also known by the brand name Narcan, the antidote was first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 1971. Advocates say it could save a child, parent or school employee who overdoses on heroin or prescription painkillers.

One Rhode Island nurse bought Narcan on her own after attending a lecture and training last fall. Kathleen Gage then took the drug into her 11th-grade health classroom to teach students how to get it at a pharmacy and use it.

“They were really enthusiastic that this could reverse an overdose, and they would have the tool to do it,” said Gage, a nurse at Pilgrim High School in Warwick, who also pushed for the state law that requires schools to buy the drug for emergencies.

Rebecca King said she has observed substance abuse as a nurse in a K-8 school in Delaware. Seeing a child collapsed on the floor is the “worst nightmare” of every school nurse, she said.

“Naloxone saves lives,” King said. “It can really be the first step toward recovery.”

Heroin overdose deaths in the United States nearly quintupled from 2001 to 2013. More than 70% of overdose deaths relating to prescription drugs in 2013 involved opioid painkillers – a class of drugs that includesheroin, oxycodone, codeine, fentanyl and morphine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overdoses at school are uncommon but not unheard of.

A survey of 81 Rhode Island school nurses who participated in a naloxone training program last year found that 43% of high school nurses who responded reported that students in their schools were abusing opioids, according to statistics released by the state health department. Fifteen said they had to call 911 at least once in the past three years for suspected student substance use or overdose.

From July 2014 to August 2015, 29 children ages 17 and younger received the drug in Rhode Island, according to the health department. During that time, naloxone was administered once at a school, although it was later determined that the person had not overdosed.

One of the children given Narcan was just 4 years old. The details of that case were not clear, but some nurses said they worried about an overdose by a curious child with access to a relative’s drugs.

Some districts have struggled with whether to add the antidote to their medical supplies.

School officials in Hartford, Vermont, last year decided not to stock Narcan because of liability concerns and worries that people who receive the drug could become combative when awakened. But they changed their minds last month, with school board members citing the drug’s low cost and the region’s drug-abuse problems.

Those who have experience with the drug stress that it is safe even if given to someone who has not overdosed.

People coming to are often groggy and confused and may experience withdrawal, but they do not typically become violent, said Laura Byrne, executive director of the HIV/HCV Resource Center in Lebanon, New Hampshire. She has given doses of Narcan to some school nurses who asked for it.

To allay concerns that school employees could be sued for giving a life-saving drug, the Rhode Island law says no one can be held liable for using it or be disciplined for refusing training.

Laws in Kentucky and New York explicitly allow school employees to obtain and administer naloxone and excuse them from liability for using it in an emergency. Illinois does not require schools to carry it but allows nurses to administer it.

Delaware passed a resolution this year endorsing expanded access to naloxone in schools. Since then, its 40 high schools have received donated auto-injector kits that normally cost $500 or more each.

Some lawmakers have raised questions about whether manufacturers raised the drug’s price just as more cities began using it to reduce overdose deaths. But the school districts do not expect to spend much.

At $25 to $40 per naloxone dose, Rhode Island planned to spend only a few thousand dollars to put naloxone in around 115 schools. And schools won’t go through the doses quickly, as EMTs or other front-line health workers might.

In Massachusetts, nurses in more than 200 school districts have been trained to use the antidote. The Boston suburb of Easton paid less than $100 to equip the middle school and high school with naloxone in the nurse’s office.

Superintendent Andrew Keough said he has heard no complaints from parents and likened the decision to keeping on hand a heart defibrillator or an EpiPen, a pocket injector used to treat severe allergic reactions.

“We haven’t had an emergency like this,” Keough said. “But if we did, we know that seconds really count.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion