In the years before Hurricane Katrina, residents of New Orleans sought solace in the belief that the Crescent City could build itself out of all environmental threats. Despite a sinking urban footprint, a shrinking coastal buffer and rising sea levels, they had faith that strong stormwater infrastructure was enough to keep them safe. The huge, federally built levee system encircling the metropolitan area enshrined that belief.

But then, in late August of 2005, the levees failed, allowing Katrina’s storm surge to flood roughly 80% of the city, killing hundreds and damaging 134,000 housing units. The catastrophe shattered faith in the US Army Corps of Engineers, which had designed the levees, and sparked a complete re-evaluation of the region’s flood defences.

In truth, though, the fate of New Orleans was decided long before the storm hit. According to Richard Campanella, a Tulane University geographer, the full backstory of the catastrophe stretches back a century or more. “There are some people who only put the focus [of what happened] on engineering factors,” Campanella says. “Frankly, all of us were either indirectly or directly culpable.”

Manmade levees and drainage systems long ago reduced the threat of the great Mississippi river’s seasonal flooding, allowing New Orleanians to expand their metropolis over generations. But that same infrastructure set in motion environmental shifts that made the city even more vulnerable to storms.

“If you look at post-1930s development in New Orleans in contrast with pre-1930s development, you’ll see a city that lived with nature for much of its history and then engineered itself out of its natural environment,” says Jeff Hebert, director of the New Orleans Redevelopment Authority and the city’s chief resilience officer, a position funded by the non-profit Rockefeller Foundation. “So a lot of it is, we need to jump back to what people knew to do in the beginning – when we knew how to live in this environment. We cannot just wall ourselves off from it.”

In this sense, New Orleans’s storm defence is a paradox. While physical walls and pumping stations make up the city’s baseline of protection, there is inherent friction between today’s storm defences and the geographical realities that could worsen tomorrow.

“The establishment of New Orleans here … commenced an ongoing 300-year project of imposing human-engineered rigidity to a fundamentally fluid natural foundation,” Campanella says. “We’ve been able to create a metropolis, but we’ve interrupted those [natural] processes at the same time.”

After Katrina, the Army Corps rebuilt the metropolitan area’s 133-mile flood protection system – earthen levees, floodwalls, gates, pumps – with $14.5bn (£9bn) from the US Congress. The new system takes a “military approach”, the army recently explained, as “the perimeter has been pushed out and is now more heavily defended”. Levees have been reinforced to limit the chance of being washed away if overtopped by an especially high storm surge – a key improvement since Katrina. Construction on an enhanced drainage system, initially authorised in 1996, continues.

“That’s going to allow us to double the drainage capacity in those areas,” says Cedric Grant, executive director of the city’s Sewerage and Water Board. “The baseline [of protection] now is much higher than it was in the past.”

But such infrastructure carries unintended consequences. Drainage and then development of the city’s backswamps over the past century has led roughly half of New Orleans’s land to sink below sea level. The levee system has also prevented the Mississippi from flooding and, in turn, nurturing the surrounding coastal wetlands that act as a buffer to storms here.

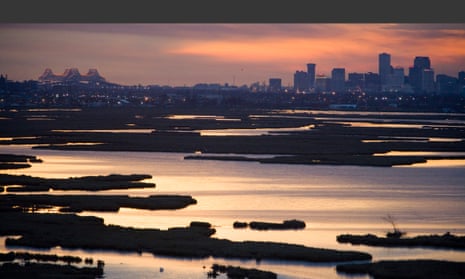

Between 1932 and 2010, about 1,900 square miles of such land disappeared from southeast Louisiana, according to the US Geological Survey: a 25% decrease in aggregate area. Louisianans, who tend to scale the disappearance in terms of their favourite sport, put the rate at about a football field every hour.

“If nothing is done, in the next 15 years, another 300 to 500 square miles of Louisiana will disappear,” John M Barry, a historian and former member of one of greater New Orleans’s levee boards, wrote recently in The New York Times. “And loss will continue after that, turning New Orleans into a potential Atlantis with walls of levees holding back the sea.”

The origins of New Orleans

Over thousands of years, the Mississippi river pushed the toe of Louisiana’s “boot” outward by shooting sediment from its drainage basin out into the Gulf of Mexico. Periodic flooding, meanwhile, spilled muddy water over the river’s edges and deposited sediment on the land alongside them, creating high ground. These natural levees were tallest near sharp bends in the river, one of which is where French colonists founded New Orleans in 1718 – hence its Crescent City nickname.

Throughout New Orleans’ first two centuries, development was densely clustered on this natural levee, making residents less vulnerable to flooding. Buildings were often designed with storm water in mind.

“On the highest ground, houses on heavy foundations were raised on pillars high enough to allow water to stream beneath without drowning inhabitants – and without causing much structural damage,” wrote Kristina Ford, the city’s former planning director, in her 2010 book The Trouble with City Planning.

But massive drainage systems installed in the late-19th and early 20th centuries emptied out city-owned cypress tree swamps behind the natural levee. New technologies opened up land that had previously been regarded as uninhabitable. And an increasingly complex, man-made levee system kept it dry enough for massive development. This isn’t to say that no one foresaw potential side effects, but rather that the upsides seemed to outweigh them at the time.

“No doubt the great benefit to the present and two or three following generations accruing from a complete system of absolute protective levees, excluding the flood waters entirely from the great areas of the lower delta country, far outweighs the disadvantages to future generations from the subsidence of the Gulf delta lands below the level of the sea,” civil engineer EL Corthell wrote in a National Geographic article in 1897.

The drainage projects opened up air pockets in the soil beneath New Orleans. And without floods to fill those pockets, “the organic material of those former swamps has been shrinking and settling like a drying kitchen sponge,” wrote geographer Peirce F Lewis in his 1976 book, New Orleans: The Making of an Urban Landscape. The metropolitan area sank at a mean rate of roughly 5 millimetres a year between 1951 and 1995, according to a USGS study, much of that subsidence occurring in the city’s formerly uninhabited backswamps.

Federal housing policies, coupled with the postwar economic boom, allowed hundreds of thousands of residents seeking the middle-class dream to swarm into these areas. The result was a massive population shift into increasingly low-lying neighbourhoods. Whereas nearly all of New Orleans’s population resided above sea level in the early 1900s, only 48% did so by 1960, according to a forthcoming paper by Campanella. By 2000, that number had dwindled further to just 38%.

What’s more, the modern, seemingly infallible stormwater protections lulled builders into complacency. “Most [houses] weren’t raised above ground level, since flooding seemed ‘impossible’,” Ford wrote. “Building materials were no longer chosen for their resistance to water in the manner of the old cypress construction.”

Historic neighbourhoods sitting on high ground, such as the French Quarter and Garden District, were relatively unscathed after the post-Katrina flooding. But newly built, low-lying neighbourhoods – Gentilly, Broadmoor and New Orleans East, to name a few – were devastated.

The great debate after the disaster centred on whether areas at such high risk should be redeveloped at all. Not doing so would have restored New Orleans’s more traditional urban geography, and likely reduced the potential threat of stormwater. But the public outcry at the suggestion, which would have affected predominantly African-American neighbourhoods, led city leaders to shelve the proposal.

Since Katrina, the proportion of metropolitan New Orleans residents living in areas above sea level has risen only fractionally, from 38% to 39%, according to Campanella – “although the change represents the first-ever reverse” of the city’s century-long migration to areas below sea level.

Many of the residents who returned to those low-lying neighbourhoods have raised their houses off the ground – an expensive proposition. The elevation grants awarded through the state’s Road Home programme – up to $30,000 per home – often didn’t cover the full costs of such projects, while spiking insurance rates have likewise added new costs to living in these areas.

For its part, the city has improved urban evacuation plans, strengthened public structures, and partnered with the Rockefeller Foundation to create a citywide “resilience strategy”, which will be formally launched this week. The Redevelopment Authority, headed by Hebert, has begun pilot projects for stormwater management, such as rain gardens.

“For us, [the goal] is redundancy” in the city’s layers of defence, Hebert says. “It’s looking at the structural systems that the Army Corps and others have put in – but also understanding the natural systems that we need to think about, reform, change, so we can be here for another several hundred years.”

‘The End of the World’

Venice, Louisiana, a strip of a town known for its sport-fishing, has been labelled “The End of the World” by some of its visitors. Its main drag ends as the Mississippi splinters; wetlands sprawl outward from both sides of the river as it snakes its way about 65 miles southeast of New Orleans, through Venice and on out into the gulf.

Experts hope that the understated vegetation in such areas can be the beginning of a more resilient region. The fate of these natural flood defences will decide just how often New Orleans is forced to fall back on its own, man-made systems.

It is estimated that every 2.7 miles of coastal wetlands absorbs a foot of storm surge. But over the past century, without seasonal flooding to nurture them with more sediment, land has eroded faster than the natural rate. Construction of thousands of miles of canals to serve offshore oil and gas drilling sites only accelerated this pace. Various scientific studies have suggested such manmade waterways directly or indirectly caused 30% or more of the wetland loss, allowing saltwater to creep in and kill plants whose roots keep the soil together.

In the wake of Katrina, there’s a new sense of urgency in the region to make sure such areas don’t live up to Venice’s cataclysmic moniker. A plan by the state’s Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority calls for $50bn in investments over the next 50 years to halt the loss of wetlands and restore those already swallowed by the gulf. The authority’s most recent framework, released in 2012, projects that it can halt the loss of land in 20 years and build or sustain up to 800 square miles of wetlands and barrier islands, another important defence, over the next 50.

One method of building new land, for which the agency proposes $20bn, is to dredge the Mississippi riverbed and then pump that material to areas in danger of being submerged. “Marsh creation projects will build most of their land as soon as the project is constructed,” the CPRA says, making them important options to protect areas “in dire need”.

“There are strategic pieces of marsh, strategic barrier islands, that help maintain a larger portion of wetlands than others,” says Kyle Graham, the executive director. But the agency itself concedes in its proposal that this option creates land still at risk of erosion. It’s unlikely that such efforts alone would sustain themselves over decades.

The more difficult, but possibly more effective, route is to mimic the natural process through which the Mississippi created land over the past 7,000 years. “Sediment diversion” entails controlled flooding that allows the river to deposit silt in surrounding areas. The state would essentially cut through natural levees and replace their earthen material with gates to allow some water to pass through. “Channel realignment” would go one step further, redirecting the river in a wholesale fashion. The CPRA proposal argues that “sustainable restoration of our coast without sediment diversions is not possible”.

But there’s one major catch. “A river sediment diversion has never been built anywhere,” says Graham.

Such projects take an exceedingly long time to plan and construct, and not only because they’re difficult to engineer. While controlled flooding will likely create new wetlands, it will have other repercussions as well – potentially disrupting fisheries, shipping lanes, even entire towns. The CPRA will spend the next year consulting with community members and modelling individual projects to minimise those consequences.

In the meantime, it will continue with more short-term measures. As of July, the state had about $520m in wetland restoration projects under way, Graham says, the most at any point in its history. Still, adds Chip Groat, president of the Water Institute of the Gulf thinktank, “how much we’re making in the way of gains is not very spectacular at this point. There’s not much in the way of large-scale projects being implemented.”

Should the sea level rise higher than climate scientists anticipate, Groat adds, it could throw off the complex projections and modelling needed to maximize the sediment diversions’ effectiveness. “In the early days, the pie-in-the-sky thought was to make the wetlands like they used to be,” Groat says. “Now, we’re figuring out where we can hold the line.”

The process couldn’t move fast enough for New Orleans residents, whose memories of August and September 2005 provide all-too-clear reminders of the danger of inaction. Tens of thousands who evacuated the city never returned. And many who did have faced a decade of toil to put their lives back together.

“I think a lot of people still live in fear of Katrina,” says Tonya Smith, who lives in New Orleans’s Algiers neighbourhood. “I want to be here. There’s no place like here. But you can’t continually rebuild.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter and Facebook and join the discussion

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion