If you’ve felt uncomfortably hot in a city this summer, chances are it’s not just because of the weather. Look around any urban centre and you’ll see the built environment itself exacerbates summer temperatures.

Vehicles stuck in traffic emitting heat. Airconditioners pumping waste heat into the air. Concrete and asphalt across almost every surface, absorbing and radiating the sun’s rays. Urban canyons formed between tall buildings, trapping heat at the street level.

All these factors contribute towards a phenomenon called the “urban heat island” effect, which results in cities being up to 10C hotter than the surrounding countryside. How do we to tackle this?

A typical response on a hot day might be to turn up the aircon. But this fuels a vicious circle of heating the outdoors to cool the indoors, making external spaces more uncomfortable still, and at a significant cost. Airconditioning currently accounts for around one-fifth of building-related global electricity usage, or 2.5 timesthe total electricity use in Africa.

- A thermal imaging photograph of Sydney shows high surface temperatures of asphalt roads and buildings, with lower temperatures in the shade

With a warming climate and rapid population growth in hotter, increasingly wealthy countries, our use of airconditioning is set to skyrocket in what the International Energy Agency calls a “looming cold crunch”. They estimate that the energy needed for cooling buildings will triple by 2050 – a growth equivalent to the current electricity demand in the USA and Germany combined.

Yet our disproportionately warm cities do not simply pose an energy challenge. Ultimately, urban temperature presents us with life-or-death situations; an increase in mortality and strokes is reported when temperatures head above 25C. In the US heatwaves kill more people on average than any other natural disaster, while in the UK heat-related deaths are set to increase 257% by 2050 and 535% by 2080. And it is not just an issue in hot countries – in Moscow an estimated 11,000 people died due to a heatwave in 2010.

- The Cityscape: get the best of Guardian Cities delivered to you every week, with just-released data, features and on-the-ground reports from all over the world

With the frequency and intensity of heatwaves increasing we need to urgently tackle the excess heat we face both inside our buildings, and in our cities’ outside spaces. Fortunately, there are many ways in which we can mitigate the urban heat island effect – while also creating more attractive places to live, work and play.

Gardens in the sky

As is obvious to anyone who has sat under a tree on a hot day, vegetation can be a powerful tool in the fight against excessive city heat. Not only does greenery provide shade, it stimulates evapotranspiration, the process by which water evaporating from plants’ leaves reduces the adjacent air temperature.

Many cities recognise the value of parks and trees for urban cooling, not to mention residents’ psychological wellbeing, but few have embraced greenery to the extent of Singapore. The city-state embarked on its ambitious “garden city” plan in 1967 through intensive tree-planting and the creation of new parks. As the population grew and buildings got taller, the focus shifted to include skyrise greenery encompassing “skygardens”, vertical planting and green roofs.

Today Singapore accommodates 100 hectares (240 acres) of skyrise greenery, with plans to increase this to 200 ha by 2030 – an area equivalent to Regent’s Park. This growth is fuelled by building regulations such as the Landscaping for Urban Spaces and High-Rises (Lush) policy. Lush requires any new building to include areas of greenery equivalent to the size of the development site. These can be at ground level or at height, and often include luxuriantly planted balconies, shaded skygardens and vertical green walls – which can help cause temperatures to drop by 2-3ºC.

- Green buildings in Singapore

Many new buildings go far beyond the minimum required. The Oasia Hotel, designed by WOHA Architects, accommodates greenery across virtually every surface. Wrapped in a dramatic 200m-tall planted trellis, the building almost drips with vegetation, and is wildly at odds with the corporate steel and glass of many urban structures.

“We’ve almost created, in some ways, the notion of a huge tree in the city,” says Wong Mun Summ, Founding Director at WOHA. “[It’s] a device in the city that really supports a thriving eco-system three-dimensionally in a very dense environment.” The result is a building that accommodates greenery equivalent to 11 times its own footprint. As well as cooling, such abundant vegetation contributes many other benefits too – absorbing pollutants from the air, producing oxygen and creating a calming, natural setting within the hyper-dense city.

Reflective roofs

If we are to make cities cooler we must also change the materials they’re built from. Urban areas are dominated by dark and hard materials – concrete, asphalt, paving – most of which absorb, rather than reflect, solar radiation. According to Australia’s Cooperative Research Centre for Low Carbon Living, conventional paving can reach temperatures up to 67C and conventional roofs up to 50–90C on a hot day.

Such temperatures can have significant health impacts. According to Arthur Rosenfeld of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, living on the top floor of a building with a dark roof was identified as a risk factor of mortality in the 1995 heatwave in Chicago. “Government has a role to ban or phase out the use of black or dark roofs, at least in warm climates, because they pose a large negative health risk,” he said.

The best way to overcome this is to use cool coatings– typically lighter pigments in asphalt or white-coloured coatings applied to roads, roofs and facades, which reflect more solar energy away from the city.

- Trials of a reflective road coating in Los Angeles

The New York Cools Roofs initiative, for example, has seen more than 500,000m² of roof space covered in a white reflective coating, saving an estimated 2,282 tonnes of CO2 per year from cooling emissions. Cool roofs are installed at no cost in public buildings, for non-profit organisations and in affordable housing. In other buildings free labour for installation is offered by the city with the owner just paying for the materials.

It may sound simple, but the results can be significant – research by Nasa has suggested a white roof could be 23C (42F) cooler than a typical black roof on the hottest day of the New York summer.

In Los Angeles, it’s roads, not roofs, that arethe challenge. More than 10% of the city’s land area is black asphalt, which absorbs up to 95% of the sun’s energy, contributing to the urban heat island. The city is responding by painting roads in a white-coloured sealant with a high reflectivity, at a cost of $40,000 per mile. Initial measurements suggest a reduction in temperature of 10-15ºF, though one road was found to be as much as 23F cooler after painting.

Water: a tool to cool

Water has been used as a tool to cool cities for centuries. The 14th century palace of Alhambra, for example, housed courtyards with pools and arching fountains, stimulating the evaporation of water and cooling the hot, dry Andalusian air.

The contemporary heat-proof city could follow suit, accommodating ponds, pools, fountains, sprinklers and misting systems to cool outdoor spaces.

Chongqing is known as one of the “three furnaces” of the Yangtze River Delta, given its long hot summers. To provide moments of relief, the city is experimenting by using water misters at local bus stops. These spray clouds of water chilled to 5-7C, cooling the air as well as the waiting passengers.

Combining water with other urban cooling strategies can yield significant temperature reductions. The University of New South Wales, the CRCLCL and Sydney Water studied the urban heat island effect in western Sydney, where temperatures can often be 6–10C hotter than the coastal regions of the city little more than 15 miles away and found that adding water features and cool coatings would reduce cooling requirements by 29–43% and lower the overall average air temperature by 1.5C. Temperatures taken adjacent to water features were up to 10C lower, the study found.

Dynamic shades

One of the challenges in keeping the built environment cool is overreliance on fully-glazed facades. Many windows permit desirable natural light and views but can mean buildings trap unwanted heat in summer and don’t retain it in winter. We can easily design shading systems to protect buildings from the sun, but for the best possible results, these shading systems need to move in tune with the local weather and the path of the sun.

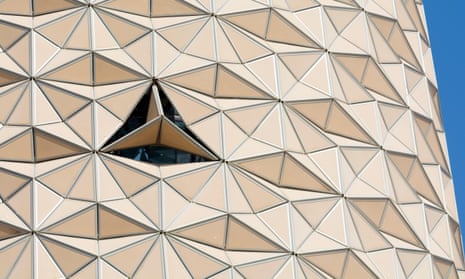

A radical example is in Abu Dhabi, where summer temperatures rise as high as 48C and buildings need to be shielded from the harsh desert sun. The Al Bahr Towers take inspiration from a Middle Eastern shading device known as a mashrabiya. Historically, these are wooden screens, patterned with Islamic geometry to allow for filtered light and views while protecting inhabitants from the intensity of the sun. But the modern mashrabiya in the Al Bahr Towers move to create a dramatic, adaptable façade, estimated to reduce the building’s CO2 emissions by 20%.

- The exterior of Al Bahr towers in Abu Dhabi

A building management system operates 1,049 hexagon-shaped shades, opening and closing them like flowers. Their movements follow the sun, shading the parts of the building in direct sunlight but opening up to allow for natural light as the sun moves by.

The result is a constantly changing and adapting façade, one that reflects daily and seasonal patterns of weather, climate and occupation and responds to changing needs of heat and light. Adaptable buildings and infrastructure like this one, which can morph to respond to different seasons and weather events, will be crucial in the future battle to keep cool and comfortable in a warming climate.

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here