On a warm summer day last July, Claire Hart and her 19-year-old daughter Charlotte went for an early morning swim at their local leisure centre in Spalding, Lincolnshire. It was a trip they made often, just a short drive from their home in the village of Moulton. Claire’s son Ryan had recently bought his mother a swimming pass as a present.

At 9am on 19 July, mother and daughter left the pool and made their way back across the car park to their blue Toyota Aygo. As they approached the car, a man crawled out from underneath it: Claire’s husband and Charlotte’s father, Lance Hart, whom the pair had left five days earlier. Now he held up a single-barrel shotgun and shot Claire three times. He then reloaded the gun and shot his daughter, before turning the gun on himself.

Alex Marchant, a manager at the sports centre, ran outside when he heard the first bang, thinking it was a car backfiring. In the distance, he saw Lance with the gun in his hand. When he got to the car, he recognised Charlotte lying on the ground. In her final moments, as Merchant cradled her, she told him, “It was my dad who shot me.”

Armed officers arrived at the scene, where paramedics attempted to resuscitate them, but it was too late: Lance was dead, and Claire and Charlotte had fatal injuries; neither could be saved.

In the confusion that followed, police put local schools on lockdown. Residents were warned to stay inside and lock their doors. Spalding began to trend on Twitter, and people speculated whether there had been a terrorist attack.

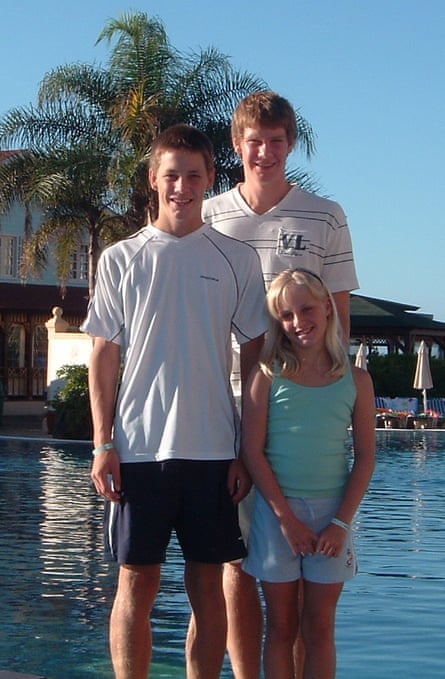

Ryan and Luke Hart – Claire and Lance’s sons, Charlotte’s older brothers – were both working outside the country at the time, Ryan in Holland and Luke in Aberdeen. But the same BBC breaking news alert popped up on both their phones: “Shooting in Spalding,” the notification read. They both tried to call Claire and Charlotte, but neither answered their phones. The two brothers started to worry: only days before, they had both helped their mother and sister move out, after a lifetime of emotional abuse and psychological control. But surely Lance wouldn’t do anything that would make the international news?

Ryan and Luke Hart sit cross-legged on the rug in their living room in Spalding. Bella, their fluffy white labradoodle, is stretched across the sofa, while Indi, a black jack russell, sits by Ryan’s feet. The small, two-storey house sits on a quiet country road, with the brothers’ car parked outside.

This is the home they rented last summer, a few weeks before Claire and Charlotte left the larger family home in Moulton. Their mother’s cutlery sits in a glass cabinet in the corner of the room next door, beside a bed the brothers couldn’t fit up the stairs and have instead placed in what should be the dining room. Luke, 27, has been living here since last July. Ryan, 26, stays whenever he’s home from his job as an engineer in Qatar. But the house was never meant to be their home. The brothers’ belongings are stacked high against the walls in the living room, as if they have only just moved in and not had time to unpack.

Luke and Ryan have always been close. Both are engineers, vegans and Labour supporters, in a staunchly Conservative part of the country. Since last summer, the brothers say they have grown even closer. For years, they were protective of Charlotte and their mother; now, their lives depend on each other.

They recall the shock of the initial news. “I looked at the BBC alert and thought, ‘What the hell is Spalding in the news for?’” Luke says. “Part of me knew, and at the same time part of me didn’t believe anything. I saw it, but then I felt like my life was a video game, like I had changed planets in that moment and suddenly nothing was real.”

The police told the brothers not to read press coverage of the attack. Luke read nothing for months, but Ryan was able to avoid it for only a few days. He was shocked to find reports that were sympathetic towards his father. The Sun and Daily Telegraph quoted locals who described Lance as “a nice guy”, while the Daily Express reported that he was “a DIY nut”. The Daily Mail spoke to others who described Hart as “always caring”. In every report, there was speculation that the prospect of divorce “drove” Lance to murder, and little mention or description of Claire or Charlotte.

“I was shocked at the ease with which others, sitting behind their desks, could explain our tragedy away within an afternoon,” Ryan says now. “It was very difficult to read that they were sympathising with a man who caused Mum and Charlotte misery their entire lives. One writer even dared use the word ‘understandable’ to justify why they were murdered.” This second Daily Mail article, a column by psychiatrist Max Pemberton, argued that a man killing his children “is often a twisted act of love”. The article was later removed from the site.

“You’re reading it and thinking, ‘This is bollocks,’” Ryan says. “But you know people around the country are also reading it, and those ideas are being driven into their minds. It reinforces in the abuser’s mind that what they’re doing is OK.”

“They kept saying this was a money issue,” Luke adds of the news stories. “It wasn’t about money. That’s what made me really angry. Sometimes news is just entertainment. They couldn’t have known our history, but it was weird: in the absence of information, they chose the side of a terrorist who committed murder.”

The Harts grew up in a big farmhouse in rural Cambridgeshire. When they first bought the house, it was so rundown that it needed knocking down and rebuilding, and the family lived for a year in a caravan on the driveway. The three children spent much of their time outside, climbing trees and wading through the waist-high grass. They played with the family animals: dogs, pigs, chickens, sheep, geese. Claire grew the family’s food on a vegetable plot. “We basically lived outside and off the land,” Luke says.

The family moved to the village of Moulton in 2001, when Luke was offered a place at a nearby grammar school. Lance struggled to keep a job for longer than a few months there, before eventually finding work at a local builders’ merchant. Claire got a job behind the meat counter at the local Morrisons supermarket, a job she held until the attack. The family earned very little. “We were one of those families where you’d have to turn the lights off, or wear more clothes because you can’t put the heating on,” Ryan says.

The brothers describe Claire and Charlotte as selfless, caring people. They both loved animals and were “obsessed” with dogs. Charlotte also loved horse riding and volunteered with the elderly. She was sporty and adventurous, but also loved to sprawl out on the floor and play Call Of Duty. Claire had survived ovarian cancer when her children were in their early teens, and had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2003. But she found happiness in the family dogs, growing her own vegetables, and mainly in her children: she would beam with pride when talking about them. Claire and Charlotte were almost like sisters: they would escape to Charlotte’s room together to do each other’s makeup and watch movies.

Like her brothers, Charlotte did well at school, and had been studying midwifery at Northampton University, where she played for the students’ union lacrosse team. She was a bright young woman with a keen sense of humour, though she had recently experienced severe depression and dropped out of her course; she was due to start teacher training at Northampton in September.

Their father took little interest in his children. He didn’t attend school events or sports matches – if they were honest, the rest of the family preferred it that way. Instead, Lance spent most of his time sitting in the corner of the living room, on his laptop. He gambled and made friends on messageboards and in chatrooms. He became obsessed with conspiracy theories, and would try to force his political views on the rest of the family.

“He seemed to like his friends online a lot more than us,” Luke says. “He didn’t have a real world – his whole world, 12 hours a day, was on his laptop. We were slowly becoming the enemy to his strange world. His delusion became his addiction.”

Around the time the family moved to Moulton, the brothers started becoming more aware of their father’s controlling nature. They say Lance became “obsessed” with the family’s money, taking Claire’s wages and rationing them back to her. Nobody else was allowed access to the family bank account. There was little money coming in, but even so Lance would treat himself to holidays, including a trip with a friend to Niagara Falls. He deemed the family dogs’ obedience training – £10, once a week – too expensive and cancelled it. He spent £300 on an exercise bike he never used. “At first, I thought the way he was with money was his way of looking after the family,” Luke says. Soon, he realised it was being gambled with, and that it would always be off limits. “Before we knew it, it was his money and we weren’t allowed to touch it.”

As Luke and Ryan grew up, Lance’s repressive nature became more obvious. Luke describes him as like a “bored prison guard”. He restricted Claire’s access to a mobile phone and social media. Once the two brothers had gone to university (Ryan to Durham and Luke to Warwick), they had to call their father and ask to be put through to their mother. When they were home, they recall nights when Lance would drink a bottle of whisky and yell at Claire all night, preventing her from sleeping. Her multiple sclerosis was regularly triggered by his erratic behaviour, they believe; she would suffer serious attacks that lasted up to half an hour, the pain throbbing in her face. If she tried to meet friends from work, Lance would accuse her of being gay, or having an affair. He would guilt-trip her for weeks for spending £3 on a cup of coffee. She wanted to travel around Europe, but Lance hid her passport. He refused to let her visit Ryan when he did a triathlon in Turkey, even though the only reason Ryan entered and trained for it was so his mother could come and see him, and have a holiday.

While the children grew closer to Claire, Lance withdrew. He became angry and paranoid that his children weren’t “like” him, believing they were conspiring against him. It took very little to trigger an irrational reaction. “Charlotte once forgot to fill up the kettle,” Luke says, “and for three hours he was marching around the house, yelling at us about it. Even when we filled it, he’d keep going, slamming the doors, screaming at us.”

Luke recalls that, when Claire told the children she had ovarian cancer, Lance “huffed and puffed” at the dinner table. He complained that the children “didn’t know what it was like for him to have a wife who had cancer”.

“He was always jealous if you were happy,” Luke says, “and if you were upset, he was jealous of your suffering. It was about inflicting his own emotional state upon us – say, he’d come back from work and he was happy, he would angrily force us to laugh and join in. He wouldn’t even let us live an emotional life free from him.”

Lance was not physically abusive – largely, the brothers believe, because they all worked hard to orchestrate a calm atmosphere at home, and because they gave in to his emotional demands. They didn’t think of his behaviour as domestic violence, because they had only ever considered domestic violence to be a man hitting a woman. Lance didn’t consider his actions to be abusive, either. “Yes, we bickered, but it wasn’t serious,” he wrote in his suicide note. “It was normal marriage stuff. No violence.” For some months, Claire had been keeping a diary of everything Lance said and did, but didn’t feel she could take it to the police because there had been no physical harm.

“We thought, ‘Well, he’s not drunk and beating us every weekend, we’re not failing at school, we don’t have behavioural problems.’ Those were the signs I was looking for,” Luke says. “And because it hadn’t happened, we didn’t recognise our suffering, or that he was dangerous. From the outside, we were three healthy, intelligent children. No one seemed concerned that much was wrong, because we were doing so well.”

The brothers and their mother talked about leaving the family home, but hadn’t the money to do it. So they decided to play the long game instead: to adapt to their father’s irrational behaviour, keep their heads down and save money. “We knew from a very young age we would leave,” Luke says. “And I think he always knew that one day we would leave. We had to plan for 15 years in the future. Mum was ill and Charlotte was young. Half the reason I worked so hard at school and work was because I wasn’t doing it just for me.”

After Ryan graduated from university, their escape plan started to take shape. Last June, Claire told her husband she was going to leave him, but Lance attempted a reconciliation. Home from Holland for a week-long visit, Ryan remembers seeing his father change. “It was creepy, seeing him smile and act like he was nice. You could tell it was acting.” But Ryan says it lasted only a day or two. “Once she didn’t fall for it, he turned evil.” He threatened to burn down the house. He told Claire he would fabricate lies about their sons’ student loans to get them thrown into jail.

On Wednesday 13 July, Luke and Ryan travelled home to Spalding to help move their mother out, staying in a hotel for the night. At 8am the next morning, they picked up a removals van and drove it to the family home in Moulton. They knew Lance would be at work by the time they got there and texted Claire to say they had arrived. There was no answer. Lance had driven her to work against her wishes, so they went to pick her up. Claire told them his behaviour had been especially bad that morning. They hurried to load the van, sweating in the heat: Lance was unpredictable, and they knew he could return at any moment. The dogs jumped in the van, and once they were all crammed inside, they drove to the rented house.

“Everything felt uncomfortably different,” Luke says, “but I later recognised that the feeling was simply freedom. It was something I’d never known or felt before. We felt reborn.”

On 18 July, four days after Claire Hart moved out, Lance returned a rental car he had been borrowing, on time, to avoid the late fee. He cooked himself a meal he described as his “last supper”. After he carried out his attack the following day, Lincolnshire police discovered a 12-page suicide note he had saved on a USB stick left inside his car, labelled “To whom it may concern”: “I have just had my favourite meal, paella, and I’m sitting in the sun with a glass of red wine,” He attempted to justify himself, addressing Claire: “You have created a screwed up mind… Right or wrong, I had to do this. You destroyed my life without giving me a chance, so I will destroy yours. Revenge is a dish best served cold. Karma is a bitch.”

When Luke and Ryan returned to the family home after the attack, they found their father’s to-do list on the kitchen counter. “It was so coldly ordinary,” Luke says. “It included things like ‘Buy a secondhand fridge’, even though he only planned to use it for a few days.”

On Lance’s computer, they found evidence that he had begun to plan the murders three weeks earlier, and not just over the four days since Claire had moved out, as the media had reported. He had recently searched for articles about men who murder their wives. One Google search read: “how many men kill their wives”. “I think he wanted to feel he wasn’t being different, and that other men were like him,” Ryan says.

What the brothers see as the normalisation of their father’s actions in the press concerns them. They have asked themselves: what if other men search for articles about men who murder their wives? And what if they come across the sympathetic articles about Lance?

On the day of the attack, the police told the public that incidences such as these are “incredibly rare”. But just six weeks later, in County Cavan, Ireland, a woman called Clodagh Hawe and her three children, Liam, 13, Niall, 11, and six-year-old Ryan, were killed by Alan, her husband and the boys’ father. “And who knows,” Luke says, “that man in Ireland may have read one of the articles that described our dad as a nice guy.”

It is only in the past year that other pieces of their childhood have fallen into place, the brothers say. “When we moved from our first home, we were told it was because of my school,” Luke says. “But family members later told us it wasn’t that – they said he [Lance] fell out with everyone, hid, and that he ran away from our old home. He couldn’t keep a job in Cambridgeshire, socialise or fit in. A lot of people we knew growing up there didn’t even know we’d left. At the funeral, some of them said, ‘Where have you been for 15 years?’”

One family friend asked if Claire had been having an affair that might have “triggered” the attack, a theme that echoed some media reports. Others asked if it was because of money, because Lance resented his children, or why Claire had stayed for so long. After the initial shock, the brothers say they have grown weary of the victim-blaming that came from both the press and people they knew. “The reality is, you can’t stay and you can’t leave,” Luke says. “You have no options. And it shouldn’t be that the burden is on the victim to run away to survive.”

What their father did was not unpredictable, random or unstoppable, Luke insists. It was part of a familiar pattern of male violence, carried out by a man with what Luke describes as “traditional masculine views”. Lance Hart was an ordinary man, who had no mental illness; he was like many other ordinary men who kill their families.

“He didn’t lose it,” Luke says. “When we got to the house, there was a to-do list, so he was functioning fine. And that’s the problem – there are many ordinary men just like him. People pretend it was random, because then they don’t have to confront the difficult issues causing it: the way men can behave and what they believe. He was willing to destroy the world before he changed his beliefs.”

In April this year, on Ryan’s 26th birthday, Luke posted on Facebook an emotional tribute to his “strong little brother”, mother and sister. Ryan had more often been on the receiving end of his father’s anger, he wrote; he was also “exactly the kind of man the world needs more of”. The post has been shared more than 3,000 times and the brothers now want to raise awareness of the complexities of domestic violence, an issue they say the British overlook as “an awkward situation”.

“It seems like no one wants to do anything,” Luke says. “No one wants to say, ‘This is going to happen again next week.’ If we don’t [talk about it], other people in our situation won’t see the severity of it.” He believes they would all have been better off without a father. The central male figure in their lives was “useless, controlling and arrogant”, and the brothers say they now see overtly masculine figures as “pathetic”. “Our father had broken beliefs about fatherhood and being a man. Sometimes, women worry, ‘Oh, if our child doesn’t have a father figure, who knows what will happen to him?’ Well, he’ll probably just turn out to be really nice, actually,” he laughs.

“For the last five to 10 years, I was trying to learn from him what not to do,” Ryan adds. “I based my decisions on watching what he’d do, then I’d do the opposite. But I hadn’t realised he was any worse than other fathers. I thought all men were like him.”

They now want to live life the way Claire and Charlotte would have wanted them to. Their favourite thing is to walk Indi and Bella, because their fondest memories are of their mother and sister playing with the dogs. They refuse to see Claire and Charlotte as victims. “Vulnerable women and children are not treated as heroes, for standing up to their oppressors even when they are murdered, or given a national day of mourning,” Luke says. “But they should be.”