We come into the world wide-eyed, ready to stare. And after we are done crying, eyes scrunched tight against the raw light, we start looking, which is the precise moment we begin to live in the company of humans. Nonsense, I was told; newborns can’t see a thing; blind as a bat. Takes days, weeks, to make out anything. But I knew better.

A grim rain was falling on Boston in the early hours of 15 May 1983. The soundtrack of my daughter’s birth was Vivaldi and typewriter. No hospital staff wrote reports on computers at that time; Vivaldi was the obstetrician’s idea. As my wife was wheeled into the ward, up bounced the Jerry Garcia of obstetrics: flower shirt; jeans, distressed (but not as much as me). First words out of Jerry’s mouth were: “Music, man; you brought music, right? Gotta have it. What’ll it be?” Not “Sugar Magnolia”, I thought, and definitely not “Truckin’”. Embarrassed even as the word left my mouth, I went lofty on him. “Schubert?” Jerry’s brow furrowed. “We got Vivaldi, I think.”

And we got daughter. Around 2 am, the rain hammering down on Brookline Avenue, a girl was lifted from the pond of blood, howling on cue, wiped clean of vernix and set in my trembling arms.

She stopped crying. A heavy sleep descended. But then after no more than 10 minutes, and possibly less, she opened her eyes, unnaturally enormous in a smooth, open face. Those pupils were fully operational, the irises a startling cobalt. We looked at each other through clouded vision, giving each other the once-over. So much for the received wisdom. I knew my daughter was staring at me, and with an intensity that made it feel like a mute interview for fatherhood. She looked worried; we exchanged anxieties. I was not confident I had got the job. But I was sure we had made a connection; so sure that I moved my head a little to the right. Which is when it happened: the ocean-dark eyes with their big, black pupils followed the movement of my head. I took the experiment further, extending the range of my head movement; right and left, two or three times in each direction. Every time, the baby’s eyes tracked mine. This is not what one has been told, I said to myself. But this is undeniably happening. We were face to face.

Thirty years on, science has no doubts. The first thing newborns do, if all is well, is howl. Who can blame them? It’s a rough ride. But when they open their eyes, they can make out, albeit in blurred forms, the bits of a face that count: eyes, nose, mouth, hairline; the contours of the head. Their engagement with that face is immediate and intense; the strong contrasts between light and shade help. Very quickly, the attraction fastens to more than those contrasts. Presented with pictures of scrambled features or an upside-down face, the baby of but a few weeks loses interest, already deciding that this jumble of lines and shapes is somehow an unimportant distraction. A face with closed eyes will also leave her cold. Humans are the only primates to have so large an area of white sclera surrounding the darker iris and pupil, and this helps to attract the attention of the infant.

Focus pulls tighter, and by four months the baby can distinguish between different faces, establishing clear preferences for those most familiar. Smiles arrive in response to those repeatedly given by mother and father. Abrupt removal of the familiar face triggers distress. At this point, no later than six months, the baby has become an accomplished face reader.

Astonishingly, the cerebral equipment at her command to process this information has developed to the point at which its operations are as complete as they will be for the rest of her life. And this has been accomplished at a time when the infant is still incapable of differentiating other kinds of objects. Research at Princeton University has revealed that a reading of one 10th of a second is enough for us to decide whether we trust or mistrust a face, whether we want to engage or disengage from a countenance: a mere Tinder-swipe to settle our allegiance into a resolution no mere speech is likely to alter. It is this elementary social wiring that makes portraiture the most basic of all the genres of the visual arts.

Portraits have always been made with an eye to posterity, to recreate a presence where there is, for whatever reason, absence. Erasmus of Rotterdam sent the picture of himself made by one friend, Hans Holbein, to another, Thomas More, that he might be remembered vividly, which is to say as if still alive and nearby.

A portrait must offer a good likeness, so the truism holds. But this raises an enormous question: a likeness of what, exactly? Which of the innumerable faces we put on for as many occasions; some public, some private, some that arrive unbidden? Do subjects want artists to agree with their assumption that the best-looking version of themselves also happens to be the most truthful? The challenge for any artist trying to capture the lifelikeness of the subject is that a face may freeze into a mask and this may be what is transcribed on to the canvas. The greatest of all portraitists – a Rembrandt or a Goya – caught their subjects as if temporarily halted between a before and an after: an interruption of the flux of life rather than a becalmed pose.

The petrified face only reinforces the obligation of the artist to crack it and get at the essential character lying beneath the mask, the person, which is always more than an inventory of features. But suppose there is no essence to unearth from beneath a variety of the appearances we assume as the day demands: the office face, the party face, the teaching face, the flirting face? Or that one of those faces, shadowed with introspection, may be as much the authentic picture as its exuberant, outward-facing opposite?

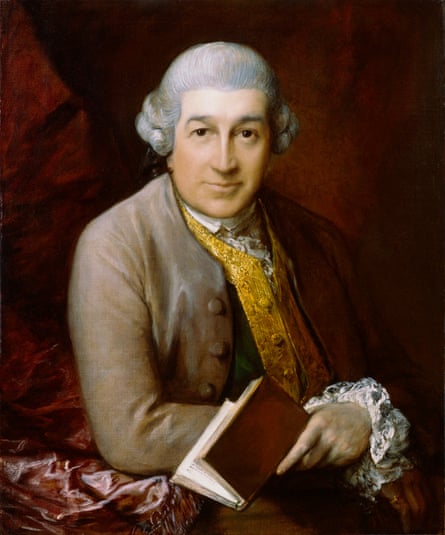

When it’s a Gainsborough or a Lucian Freud who has pictured an otherwise unknown and private person, we take it on trust that the portrait has managed to nail the qualities that made them them. But when the “history” of the sitter is portrayed for the history of the world – or the country – he inhabits and must somehow be both exemplary and individual, the challenge becomes daunting. For the painter is now answering not just to the self-image of the sitter, and the creatively disruptive urges of his muse, but to a third party that must be satisfied: public expectation.

Those expectations were institutionalised in the founding of the National Portrait Gallery in 1856, the first such gallery in the world (though France had established its pantheon for its grands hommes (sans femmes, cela va sans dire), and Poets’ Corner in Westminster Abbey had done much the same in tomb sculpture. The impulse behind it was to tell the British who they were, via a procession of two-dimensional heroes. For all the self-assurance of the Victorians, it was not accidental that the question was put at a time of sudden imperial uncertainty in India and the Crimea. What was wanted, then as now, was a gathering of characters who “stood for” Britain yet were not waxwork ciphers of a nation but, rather, a gathering of individuals still alive enough in their painted incarnations for us to feel at home in their company.

In the hands of a sympathetic painter, figures come to life. Thomas Lawrence captures William Wilberforce, his pose bent not by the artist’s instructions but by the dreadful iron contraption his deformed spine was obliged to endure. In the painting, left unfinished at Lawrence’s death, the face of the hero is lit by the sweet animation almost everyone acknowledged. Likewise, the sublimely crazed Laurence Sterne is caught in a twist of his torquing mind by Joshua Reynolds. The eyes of Harold Wilson, painted by Ruskin Spear, glance sideways through the curling pipe smoke as if there is something, or someone, the sitter ought not to miss.

These moments when actual people emerge from the paint are all the more impressive because, if we know one thing about the British, it is their perennial suspicion of the self-preening of the great and the good. So what the gallery documents is not a parade of the grand but the struggle to magic from the triangular collision of wills between sitter, artist and public the palpable presence of a remarkable Briton.

Yet there are times when the three-cornered contest tears the subject apart and all that is left are lamented remains. One of those times was the autumn of 1954.

“How will you paint me?” said the prime minister Winston Churchill to the artist, immediately narrowing the alternatives: “The bulldog or the cherub?”

“That depends entirely on what you show me …. sir,” replied the painter, trying not to be intimidated.

The signs were not promising. On this first visit he had been made to wait in Churchill’s book-lined study before a nose appeared around the corner of the door. Just a nose, in advance of the famous face. In due course, the rest of Churchill followed: rounder, pinker, flakier, wispier, jowlier than most people, including the artist, imagined. A softly cushioned hand was extended. A tiny starburst of merriment lit the old boy’s eyes. Graham Sutherland tried to put himself at ease; to concentrate his attention on the matter at hand. It was not easy.

Sitting in Churchill’s study at Chartwell, Sutherland saw what he would be up against. To bring the picture off there had to be a shared understanding. Churchill had to have an open mind about the result; Sutherland had to paint with confidence just what was in front of him, without being cramped or paralysed by the weight of National Expectations. But he could not escape the sense that all of Britain was wanting an image that would embody everything that Churchill had meant during the war: the national saviour without whose resolve they would have ended up like France, crushed by shame and occupation. The portrait that parliament and the people wanted was not just a likeness of a man, it was supposed to be an apotheosis of Britain itself: the finest hour in the form of the finest man. When this sank in, Sutherland knew he could not live up to this cult of national salvation. All he could do, he kept on telling himself, was paint what he saw.

But Sutherland’s purist insistence was arrogantly naive. None of the great portraitists – not Titian, not Rubens, not Rembrandt, not Goya, not Reynolds, not David, not Sargent – ever painted their subjects as if there were no history attached to them; or without some consideration of where the picture would end up. The adhesion of history was not something to be avoided.

Though Sutherland later said (of Churchill’s opening remark) that all he got was the bulldog, the back and forth between the two of them during the sittings was not combative. Churchill, the painter said, was charming and often very kind. None of this meant that the sittings were going to be easy: Churchill frequently arrived late, shifted his bulk about, fidgeted and, after lunch with the usual libations, could slump into drowsy torpor. “A little more of the old lion,” Sutherland would say, as tactfully as he could. The painter later said that he wanted to paint Churchill “as a rock”. But he ended up turning him into a man-mountain: weathered, glacial and steep.

Churchill famously hated the portrait – “How do they paint today? Sitting on the lavatory?” – yet what a study it was! All that we have left to judge its quality by is a transparency, since the Churchills’ loyal private secretary, Grace Hamblin, took matters into her own hands and burned the original on a bonfire lit in her brother’s back garden several miles away from Chartwell.

But the surviving image is enough to make it painfully clear that with the exception perhaps of the paintings of the Duke of Wellington by Goya and Thomas Lawrence, Sutherland accomplished the most powerful image of a Great Briton ever executed. It is not an ingratiating portrait. The bright colour of the Churchillian personality did not register in its tone. Colour, as his critics pointed out, was not Sutherland’s forte. A sour yellow ochre predominates, stained with a still-less-cheerful umber. Churchill is enthroned, but the majesty summoned in the picture is not the Henry V alluded to in his speech about the “few”, but, rather, Lear, albeit the truculent rather than the unhinged monarch. But the reason that the painting did find admirers during the brief time it had in the public view was that the bulk of Churchill, the set quality to the jaw, the expression of obdurate resolution, all added up to the immovable force Britain had most needed during the war.

For all her hatred of shadow, Elizabeth I could not stop the advancing dimness of age. But her portraits compensated by showing her as the regal source of light. The “Ditchley portrait”, where she appears as the banisher of stormy darkness, thought to be painted by Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger, commemorated an elaborate entertainment laid on for the Queen at the estate of Sir Henry Lee near Oxford. The scale was so lavish and spectacular that the cost nearly ruined Lee, and he became the butt of the sneerers when he declined to repeat it some years later. The picture, however, remained unprecedented in its union of monarchy and geography, for Elizabeth’s reign also saw the production of detailed maps of the kingdom. Elizabeth stands with her feet planted on Ditchley, the giantess-goddess of her dominions, the personification of England. Behind her left shoulder a tempest rages, struck by bolts of lightning. But the storm loses force in her majestic presence. Over her right shoulder sunlit clouds are parting and the sky is coloured the cerulean blue of peace. An inscription acclaims her as the “Prince of Light”.

The theme of royal radiance gets its consummation in the prodigious “Rainbow portrait”, possibly painted by Isaac Oliver for Robert Cecil and still in his spectacular mannerist palace of Hatfield House. Elizabeth has become sun as well as moon. Her hair (or rather her wig) is brilliant with the red‑gold of its benign rays, which form themselves into the streaming tresses falling over her shoulders. The colour is repeated on the silk lining of her cape, and on her skirts. The rainbow she grasps is the sacred sign of hope and peace, the promise of a second golden age. But without the sun-queen, there is no peace and no light.

This is just the principal element in the stupendous visual encyclopedia of symbols swarming over the picture without, somehow, choking it to death. Can an old girl (in her 60s) have too many pearls? Not this one. They drop from her throat over the bosom exposed by the deep decolletage fashionable around 1600 and from which all signs of crepey wrinkling were of course banished. No visible body part is left unpearled: ropes of them hang about both wrists; they glow from the trim of her robes; festoon the edging of the gossamer outer ruff encircling her head; a pearly threesome depends from her left ear; a circlet of them sits atop her hair, with two monster pearls set apart by a square-cut diamond; they climb all the way to the top of her fantastical headpiece, curved like the horns of an ibex, and further still again, up to its very pinnacle.

Radiance nourishes everything: the field of spring wild flowers – pansies, carnations and roses – that riot on her bodice. On her left arm the serpent of wisdom catches a heart-shaped ruby. The queen-goddess’s heart is ruled by her head. And her coat is covered with an astonishing pattern of eyes and ears, signifying her omniscient attention to the care of her subjects (not least by the institution of an intelligence service). But less noticed by commentators are open mouths clustered near the base of her rope of pearls, as well as on the opened left side of her golden coat. These are the organs of renown; a fame seen, attended to, spoken of, the wide world over.

And yet there was, for some of her subjects at least, a craving for simplicity, for, around 1600, someone commissioned a copy of the first portrait of Elizabeth as Queen, painted at the time of her coronation in 1559, and to celebrate it. It is quite obviously an adaptation of the large portrait of Richard II displayed in Westminster Abbey. Elizabeth, like Richard, is depicted frontally, ceremoniously; like him, enthroned and holding as he does the orb in one hand and the sceptre in the other. Her undressed locks proclaim her virginity. They are scarcely grown up, these two: the lad-king and the maiden queen. But one knew how to inhabit the body politic with ruthless understanding, and one did not. “Know ye not that I am Richard II?” an angry Elizabeth is supposed to have said after hearing that the rebellious Earl of Essex had staged a performance of Shakespeare’s play of deposition as a morale booster for his comrades. But the truth is she was not. Beneath the mask operated one of the most formidable political intelligences ever to have ruled in England. She knew what power lay with the royal stare. But she also knew that image was not everything.

The dark day must have been in 1955. I remember it as cold but that might be because the calamity gave me the shivers. It was the day I had to say goodbye to my own portrait gallery: to Jack Hobbs and Stanley Matthews, Steve Donoghue the jockey and Ted “Kid” Lewis the Jewish boxer, to naughty George Formby and nice Mr Attlee, to George Bernard Shaw and to Bud and Ches and the Crazy Gang, to Winston Churchill and our Sally down the alley, Gracie Fields, who wished me luck and waved me goodbye. But I couldn’t join in her song, nor was I ever likely to believe Auntie Vera when she promised me we’d meet again and that the bluebirds would really be over those white cliffs of you know where. They were all gone, all my famous ones. John Lewis had seen to that; not the Never Knowingly Undersold JL, but the dangerous, ruthless John Lewis, like me aged 10, and now, I had to concede, the supremo high-roller of cigarette-card games. We had gone head to head during lunchbreak in the playground: his collection against mine; a death-match series of Flicksies, Dropsies, and the killer, only for the truly skilled, Topsies.

Cigarette cards ended up being the people’s portrait gallery, but they began life in the last quarter of the 19th century purely functionally as an anti-crush insert in the packs. The idea of printing pictures on the cards as a bait for brand loyalty began in the US, where smokers were encouraged to collect whole teams of baseball players or vaudeville favourites. Britain began by being typically more hifalutin, recycling Victorian photographs of the Great – many of the same names that could be seen in the National Portrait Gallery – and which had already been used for cartes des visites. Thus, photographs of Disraeli, Gladstone, the Queen and the Prince of Wales, military heroes such as Gordon of Khartoum or Kitchener – even a very early picture of the elderly Duke of Wellington – were a bonus for staying loyal to this or that brand. There were also music-hall stars, Gaiety Girls, society belles, authors such as Wells and (before his fall) Wilde, and, if one had a mind to it, one might be able to collect an entire set of the mistresses of Edward VII.

The first world war may have been a graveyard for the traditional kind of pantheon, but smoking had conquered the country both in the trenches and on the home front, and had become a woman’s habit as well as that of men. Fashions and sportsmen were added to the canon, and cards now came with a dense screed of description in tiny print on the back; whether of the career of a boxer or the films of a silent-movie star. The essential thing was to make the series as extensive as possible so that collector-smokers would not flirt with Bloggs’s Virginia Gold and their golfers or racehorses. Politicians were now often represented by artfully elegant images from Punch cartoonists or caricaturists, used to doing celebrities in Vanity Fair and Bystander. Occasionally, the cards used serious talent such as Alick Ritchie, who had been trained in the École des Beaux-Arts in Antwerp before becoming a commercial artist and poster designer back in London. Ritchie acquired a reputation for mocking avant-garde art, especially cubism, but he himself had something of an art deco aesthetic, and his miniature portraits of the likes of Chaplin, Lloyd George and Shaw are tours de force of descriptive shorthand.

In addition to the famous, there were cards of everything and anything that might feed the collecting mania: butterflies and moths; old roses; dandies through history; castles of Britain; rulers of the Balkans; railway trains and steamships. The texts on the reverse became so detailed that they constituted a miniature lecture on the chosen subject. Not for nothing were sets of the cards known as “the poor man’s encyclopedia”. My own first book (written at the age of eight) was a history of the Royal Navy principally consisting of cigarette cards with bits of research borrowed from the back.

It was just as well that those treasures were not available for my last desperate throw. Of the six remaining Gallies, I flicked two: one greyhound; one society beauty. Then came catastrophe. Lewis’s Ogden landed squarely on one of my cricketers, masking it entirely. A howl of glee went up from the wall of boys watching the shake-down; something akin to the baying of hounds when the quarry is down and blood has been drawn. Lewis was on his hands and knees, scooping up his winnings: my lost treasures. I fled the scene, clutching my last four Gallies, sobbing so inconsolably that even the offer of a Marmite crumpet could not check the tears.

I had lost my portrait gallery. Now I’d have to go and see the one round the corner from Trafalgar Square.

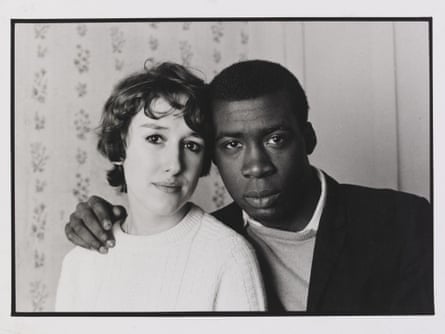

At the same time as Charlie Phillips starts taking photographs of the Piss House pub, 1968, Enoch Powell tells Conservatives in Birmingham that, “like the Roman”, he sees “the Tiber foaming with much blood” should an “immigrant descended population” settle and multiply in Britain. Charlie, born in Jamaica, sees something else: moments of unguarded happiness, many of them at the Piss House on the corner of Blenheim Crescent and Portobello Road, and he catches black and white in black and white. Later that year Charlie is minding his own business when he hears what he thinks sounds like a riot coming along the street. But it’s the first carnival; a glorious hullabaloo: drums, bands, calypso, ska, reggae, Red Stripe. Charlie grabs his Kodak Retinette and takes pictures of a sea of faces, all young, expectant as the music rolls along. It’s the answer to Powellite paranoia: no rivers of blood, just a rolling tide of happiness; bump, grind and smooch.

Charlie’s world is Notting Hill and the Grove, long before the lattes and the £200 designer jeans arrived; when the words “Notting Hill” meant the hideous race riots of 1958. Around the time Charlie was doing his paper round, I was the lanky white boy in winklepickers walking the streets my parents told me weren’t safe: Rachman houses subdivided into one room for two; two rooms for four; communal kitchens on the landings; pork-pie hats; frying kingfish; working girls in purple hot pants; the Skatalites or the Clarendonians, a rocksteady beat coming from an open window. My school was on the edge of it. After yet another detention, telling no one, not even my close pals, I hopped on a number 28 and went through the cheek-by-jowl districts of Powell’s nightmares. My parents thought I was safe and studying Talmud with the Reverend Halpern, but every so often a little jolt of adventure would sit up and beg and I’d take the 28 bus past the salt-beef bars of Willesden, past the pubs of Irish Kilburn, across the rowdy High Road and into “North Kensington”: into the Grove, where life was on the streets; where the locals of both sexes walked differently, leaned against walls differently, did everything differently; and there was no beige, tweed or corduroy. Off the bus you caught a whiff of spliff, though I had no idea then what that was, just something parched and toasty. I followed the aroma like a Bisto boy scenting magic. What kind of coffee are they roasting here? I wondered. In a doorway I would lean against the flaking stucco, and cup my hand to light a Gitane or an Abdulla, anything I reckoned smelled dark and bad. The locals laughed, the dogs growled. Both were on the biggish side.

Charlie, also known as Smokey, is the portraitist of that time and place; those streets and their people; mostly gone south of the river now, like the photographer himself. He is also a visual poet; chronicler, champion, witness of a gone world, taken by the slicing destruction of the Westway and the coming of big money. The Piss House is now a multi-floor restaurant and catering venue.

Charlie, however, is wonderfully unreconstructed. When I meet him, on the top floor of the sometime Piss House, he sports an oxblood-red borsalino, a buttercup-coloured scarf over an indigo shirt and a tie splashed with eye-scalding brilliance. An array of his photos is spread out on a table – a young black man, hands on hips in front of Westbourne Park tube; a big-mama singer at the Cue Club, elbow-length white gloves, eyes tight with Soul; a father and young son at the Friday market, answering with their stare-back all the sociological pieties about disappeared dads; another Piss House kiss, this time a real plonker, white on black. His pub, club and street moments have an unpremeditated immediacy. But there are others he must have thought about. One of them, of a young couple, his face serious, a protective arm slung around the girlfriend’s shoulder, has become a feelgood icon. Back when he took it, though, the Notting Hill riots were not long gone, and it was a defiantly brave act. Charlie remembers louts leaning out of cars in the Grove yelling “Nigger lover!” as they drove past. The picture is beautiful in recording how apprehension meets resolution. Charlie has seen the image become some sort of sociological Rorschach test about race attitudes. “What do you see in it?” he asks me. “The determination of love,” I say.

Charlie was 11 when his father brought the family from Kingston in the 1950s. In Jamaica, Britain was still cricket, fair play and the Queen. Charlie’s granny took him to Kingston to see her sweep by on a day so hot she soaked a hanky and stuck it on his little head. He thought the Queen might stop and say, “And what’s your name, sonny?” But Her Majesty passed by as crowds cheered and the Cubs and Brownies sang “God Save the Queen” at the top of their voices.

Notting Hill was a rude shock,with its NO COLOUREDS notices on the doors, one of which Charlie the archivist snapped. Hostility bred closeness. Mums and dads saw to it that the youngsters were back home by 8pm, or they got a thick ear. Still, you never knew when a brick was going to come through a window. But there was pepper-pot soup and jerk and fried plantain to get you through the bitter fogs of November. And there were the black GIs who came down from Mildenhall and the other bases, desperate for something other than steak and kidney and Watneys Red Barrel. Word of the shebeens of the Grove had reached them and they brought their own music there, along with their easy attitude and cat-like dancing. They brought records to the shebeens, and to Hammersmith Palais. No one wanted to dance to Joe Loss after Fats Domino.

Sometimes, remembers Charlie, the GIs got legless and woke up without the wherewithal to get back to base. One of them had his Kodak Retinette with him and sold it for 15 bob to Charlie’s dad, who handed it on to the 13-year-old whose only money came from a paper round fraught with the usual danger: catcalls of “nignog” and worse. The Retinette was a treasure. Charlie went to Boots, forked out some paper-round money for a Johnson’s Packet, which had all you needed to develop and print the photos. He started taking pictures of his schoolfriends; of kids, white Irish as well as black Jamaican, making faces and hooting, west London grins. One of Britain’s great photo-portraitists was off and dancing.

Search for works on facial recognition these days and you will encounter not only the vast amount of literature on a baby’s cerebral wiring that I touched on at the beginning, but something darker: a whole industry devoted to the mapping of facial features and their expressive variables for the benefit of the two leviathans that between them govern our contemporary world – the security state and the global corporation.

Companies such as Visionics Corporation, Viisage and Miro are in the business of developing and supplying technology for the ongoing (it is always ongoing) “securitisation” of identities. That means you and me. Feret is what someone with a sense of gallows humour in the defence establishment has called this Face Recognition Technology programme. Its job is to search an infinity of faces for those presenting some sort of imminent threat with techniques more sophisticated than a seated agent armed with a ballpoint pen staring briefly at a passport photo and back at a boarding pass. Eye-dentity procedures (as they were called in the 1990s) began by collecting images of the complex and unique patterns of blood vessels in the eye, usually supplementing them with electronic scans of finger traces. Iris-recognition technology is more advanced, but these Feret technologies depend on a match with an already existing database of prior suspects.

In less paranoid vein, facial databases are also being developed by marketeers to build communities of customers based on appearance-affinities. Creamy-complexioned redheads with a faint scatter of freckles and green eyes, or Amerindian faces with brown eyes and Inca noses, might then be automatically sorted into a pool to receive guided information as to nail-polish-colour preference, jewellery, theatre tickets, sports allegiance, or choice of light or heavy reading.

Against this securitisation of our faces, or, in the oxymoronic term favoured by the marketeers, “mass individuation”, it’s tempting to see the traditional portrait standing (or hanging) in a last show of defiance; capable of recording the marks of humanity in ways inaccessible to even the most advanced digital scanners. But is this, in fact, just a romance of canvas and paint? In the hands of a Rembrandt or, in Britain’s long, rich visual culture, a Gwen John or a George Romney, this is undoubtedly true. Jenny Saville’s pictures of herself and her non-stop-squirming infants convey more immediately the likeness of human vitality than anything that might be captured on video. But in the age of Snapchat, where pictures self-erase after a matter of a few minutes, and where the sheer number of selfies stored on a device militates against an emotive hierarchy, paintings or even formal videos need to be exceptionally powerful to make the case for endurance.

Faces in the sense that, say, Samuel Palmer would have recognised as bearing the ineradicable essence of character have become fungible. “Work” can be done to change them, and the day may come when plastic surgery will be as habitual as a haircut. Since genetic manipulation of the embryo can already determine the coat and eye colour of mice and rats, can the day be far off when it will be possible to choose the face of a human baby from a designer catalogue?

But this is all too postmodern for me. There is an aspect of portraiture, about the stories of its making, the locking of eyes, which I obstinately believe to be irreducible to bald data. And there is something else that bothers me, too, and against which the idea and the practice of portraiture might stand. We live at a paradoxical moment when an image is caught and then we look down at it, since that downward gaze has come to consume a monstrous part of daily routine. Whole micro-universes of sounds and sights are assembled in small machines as an extension of what we take to be the particular bundle of tastes that constitutes our identity. If we are not all Narcissus, we are nearly all Echo. We have never been more networked, yet we have never been more trapped by solipsism.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion