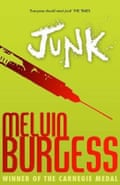

When you started to write Junk, did you think it would be published? You were one of the first authors to really explore that more adult territory?

I knew it would be published - Klaus Flugge at Andersen Press actually suggested I write a book about drugs - although I don’t think he was expecting what he got. What we weren’t expecting was for it to sell as well as it did, or win the prizes. It was the right book at the right time, and it attracted a huge amount of support as well as criticism. It wasn’t the first YA book to explore those adult territories. Other writers - perhaps most notably Aiden Chambers - had gone there before me. Junk wasn’t even the first book to be open minded about drugs, but it perhaps was the first where the characters made such bad choices and left it up to the reader to judge them.

How do you feel about Junk being referred to as a ‘dangerous’ book today, when the world of YA fiction has moved on a great deal and there are lots of novelists breaking taboos like Junk did when it came out?

It’s always flattering that people think your book might be dangerous, because it creates an air of glamour around it. Of course, it isn’t dangerous at all. The usual criticism is that young people might read it and turn to drugs themselves, but in fact, all the evidence shows that it has helped people navigate their way through that world, not tempted them into it. Like most “dangerous” books, it is in fact only a threat to people who are themselves dangerous - people who want to control others. If you want to decide what’s right and what’s wrong, to be obeyed, then any book that assumes people can make up their own minds is dangerous - but only to yourself and your little clique.

The point about novels - good novels, anyway - is that help you understand other people, with all their faults and shortcomings. The people who are scared of understanding are the dangerous ones.

Today, I don’t think Junk would get half so much publicity if published now. Doing It would though - people are still terrified of talking about the pleasures of sex with teenagers. Lust is not something people want their kids to read about. You can bet young people would read about it, though! Everyone else does.

Are the problems faced by Tar and Gemma in Junk still applicable today?

Very much so. Drugs are still glamorous and exciting, they’re very rock n roll, they provide an escape for a lot of people, a high in a world where many of us can’t afford an exciting life style - and they’re still dangerous, either because they’re addictive, bad for you, or simply because they’re illegal. Addiction is still a major problem. Junk speaks not only to people who want to play with addictive drugs, but also to people who have other, more subtle addicitons. I remember one reader writer to me to say that Gemma was addicted to heroin, but that she was addicted to “the feeling of being empty.” I assume she was talking about anorexia.

Do you feel that even today Junk is feared as a ‘dangerous’ novel?

Even back in the day, most of the fuss about Junk was in the right-wing tabloid press. There was a huge amount of interest in it when it came out, but despite all the noise, I never to this day received one single complaint to me about any dangers it might pose - against hundreds of letters and mails who were delighted by it and felt that it helped them in one way or another. All of which leads me to think that it was a press scandal, rather than a public one. The real debate is whether young people need to be ring-fenced against the dangers in society, or whether they need to be empowered. Most people, then and now, recognise that empowerment is the way forward, but it makes a quick, easy story for a lazy press.

Do you think being regarded as a writer of ‘dangerous’ books has harmed or helped you as an author?

It’s done both really. For years after Anne Fine made a very public and well publicised attack of my book Doing It in the press, I would get mails from people who had decided I was a dreadful man who wrote exploitative, sensationalist books, who had finally got around to reading my work and found, to their surprise, that they actually had genuine quality. On the other hand, there were also people who were attracted to my work precisely because of the publicity that attacks of that kind generate. Swing and round abouts…

What would you consider to be a ‘dangerous’ book?

In these days of free expression, books are a good deal less dangerous than they once were. Our democracy has discovered a secret - that it doesn’t matter what information people have, so long as there is a general consensus. Once upon a time people were kept in line by limiting the information and world view they had access to. Anything that disagreed with the prevailing ideas was stamped on very hard. You could be burned just for reading the wrong version of the bible a few hundred years ago. These days, those in power don’t care a fig what you believe in, what you read or what you write, so long as you stick within the law. As a result, writing and reading whatever you like is no longer a dangerous activity. The ones who want to ban books these days, the people who fear books and try to ban them these days are usually regarded as a bit bonkers - people who think Harry Potter is about real witchcraft, or even those who think that my book Junk is going to encourage young people to take loads of drugs and go mad.

My parents owned a good many books, and I was free to raid their shelves at will, so my reading ranged very widely when I was young. The only books I remember that I didn’t want my parents to know I was reading were rude books - pornography. People are still scared of that, even though it is so widely available over the internet now. But even then, I think that is as much because sex is such a very private activity, rather than a geuninely dangerous one.

Should young people be allowed to read anything they want? Are there any books or subjects that you really do think teenagers should be prevented from reading about?

I can’t think of any. Most people will put down a book if it’s too much for them. Reading requires active engagement - not like film, which is in your head before you have time to decide if you like it or not. Overall, we are far too cautious about young readers.

Who are your favourite modern ‘dangerous’ authors?

Hmm - I can’t think of anyone I’d regard as genuinely dangerous. As a girl once said about my own books, “It’s people who corrupt, not books.” Books are about ideas, and you can think whatever you like, whenever you like in the privacy of your own head, or in between the pages, no matter how extreme. I just had a look at various lists of banned books, and none of them were even remotely likely to harm anyone, unless you regard as not getting your own way as a personal insult. The only dangerous book is one that has a bomb in it, in my opinion.

Have you ever seen a book banned for an absurd reason?

Every single time a book gets banned is absurd.

Melvin Burgess’s latest book Persist is available at the Guardian bookshop, as are Junk, Lady: My Life as a Bitch, Doing It and more!