G

o to just about any English department at any university, gather round the coffee pot, and listen to what one of my colleagues calls the Great Kvetch. It is perfectly summarized by the opening sentence of the philosopher Martha Nussbaum’s recent book: “We are in the midst of a crisis of massive proportions and grave global significance.” She is not speaking of looming environmental disaster or the proliferation of nuclear weapons. You see, those are threats we can discern. The danger Nussbaum is highlighting “goes largely unnoticed, like a cancer; a crisis that is likely to be, in the long run, far more damaging to the future of democratic self-government.”

When a writer invokes the insidious progress of a cancer, you know she hopes to forestall the objection that there is little visible evidence to support her argument. What is this cancer threatening democracy and the world? Declining enrollments in literature courses. Her book is titled Not for Profit: Why Democracy Needs the Humanities.

And why is it, in Nussbaum’s view, that students are choosing to study economics or chemistry rather than literature? When I was growing up in the Bronx, the local Jewish deli owner, whose meats smelled vaguely rancid and whose bagels seemed to start out already a day old, attributed his failing business to the vulgarization of Bronx tastes. As her title indicates, Nussbaum arrives at the same self-serving answer. Students are interested in profit and therefore care only about pre-professional degrees. Another answer popular among literature professors is that students spend so much time on Twitter that they have the attention span of a pithed frog.

But can it really be that students are more materialistic now than in those proverbial eras of backwardness, the 1950s and 1980s? And why did those Twitterized adolescents once immerse themselves in seven volumes of Harry Potter?

Could it be that the problem lies not with the students but with the professors themselves?

Why Take a Literature Class?

O

ne reason I wonder at the Great Kvetch is that my experience has been so different. For well over a decade, I have been teaching the largest class at Northwestern University, with an enrollment of about 500 students. The course is about Russian literature. Students are generally not aware that there is such a department as “Slavic Languages,” which teaches “Russian literature.” For them it’s all “English,” which is the shorthand for studying novels and poetry, and so it is only by word of mouth that the course manages to perpetuate itself.

Students describe some literature course they took that left them thinking they had nothing to gain from repeating the experience. From their descriptions, I see their point.

The material isn’t easy. We read Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, and I devote another course entirely to War and Peace, attended by 300. Now, Northwestern is supposed to be the model of a pre-professional school. So why, of all subjects, should these students be attracted to Russian literature?

I speak with students by the dozens, and none has ever told me that he or she does not take more literature courses because every moment at school must be devoted to maximizing future income. On the contrary, students respond by describing some literature course they took that left them thinking they had nothing to gain from repeating the experience. And when I hear their descriptions of these classes, I see their point.

Why Not Just Read the Wikipedia Summary?

W

hat can students learn from literature that they cannot learn elsewhere? Why should they bother with it? For understandable reasons, literature professors assume the importance of their subject matter. But students are right to ask these questions. All courses are expensive, in money, time, and opportunity costs.

Will Rogers once remarked that “we are all ignorant, only on different subjects.” To teach anything well, you have to place yourself in the position of the learner who does not already know the basics and has to be persuaded that the subject is worth studying. You have to subtract knowledge and assumptions you have long since forgotten having learned. And one of those assumptions is that literature is worth the effort of reading it.

The first task is to get the student to want to read literature. Students certainly see the point of wisdom, guidance in how to think about their values and decisions. But professors tend to laugh at such a conception as somehow philistine. Clara Claiborne Park, who taught for years at Williams, devoted an essay to the experience of teaching literature at a community college. At the end of the semester, one farm boy asked: “Mrs. Park. We’ve read what Homer says about the afterlife, and what Plato says, and now we’re reading what Dante says, and they’re all different. Mrs. Park. Which one of them is true?” She recalls her reaction:

I suppress, just in time, the condescending laugh, the easy play to the class’s few sophisticates, who are already laughing surreptitiously…But the open seriousness on the boy’s face encourages reflection. Who, in this class, is reading as Plato and Dante would have expected to be read? And who is asking the right questions, I and my sophisticates, or this D-level student whom I have just time to realize I shall put down at my peril?

More sophisticated students usually have in mind some version of what might be called the Wikipedia test. If a book has a point, and the point can be briefly summarized, why not just read the summary? If a teacher cannot give a coherent reason why such a shortcut simply won’t do, then why should the student assume anything important is left out?

Many years ago, when Northwestern student course evaluations appeared in book form, I came across a response to a course on Dickens: “Don’t take this course unless you want to read a lot of Dickens!” The instructor assigned a novel a week. The first lecture was devoted to Dickens’s life and the second to the social conditions of the time. It obviously made no difference whether one read Bleak House or CliffsNotes.

Time and again, students tell me of three common ways in which most high school and college classes kill their interest in novels.

The most common approach might be called technical. The teacher dedicates himself to the book as a piece of craft. Who is the protagonist, and who is the antagonist? Is there foreshadowing? Above all, this approach directs students to look for symbols. It is easy enough to discover Christ symbols. Water symbolism can almost always be found, since someone sooner or later will see a river, wash, or drink. In Huckleberry Finn, the Mississippi symbolizes freedom, while the Widow Douglas’s house symbolizes civilization. In Anna Karenina, trains symbolize fate. Or modernization. Or the transports of love.

The real literary work is the reader’s experience. This means the first thing a teacher needs to do is help students have the experience the author is trying to create.

At a more granular level, this approach involves teaching a dense thicket of theory focused on “the text.” But literary works are not texts; that is, they are not just words on a page linked by abstruse techniques. Does anybody really believe that Dickens set out to create a sort of puzzle one needed an advanced humanities degree to make sense of? And that he wanted the experience of reading his works to resemble solving a crossword puzzle? Would he have attracted a mass audience if he had?

Literary works are not texts in that sense. The text is simply the way the author creates an experience for the reader. It is no more the work itself than a score is a concert or a blueprint a creation capable of keeping out the rain.

No, the real literary work is the reader’s experience.

This means the first thing a teacher needs to do is help students have the experience the author is trying to create. There is no point in analyzing the techniques for creating an experience the students have not had.

Students need to have such experiences, and not just be told of their results. It is crucial for them to see how one arrives at the interpretation and lives through that process. Otherwise, why not simply memorize some critic’s interpretation?

I once delivered a paper in Norway on Anna Karenina, and a prominent scholar replied: “All my career I have been telling students not to do what you have done, that is, treat characters as real people with real problems and real human psychology. Characters in a novel are nothing more than words on a page. It is primitive to treat fictional people as real, as primitive as the spectator who rushed on stage to save Jesus from crucifixion.” Here is the crux of it: Characters in a novel are neither words on a page nor real people. Characters in a novel are possible people. When we think of their ethical dilemmas, we do not need to imagine that such people actually exist, only that such people and such dilemmas could exist.

Readers who mistake theater for reality are vanishingly rare, but almost every reader spends time wondering what she would do if she were to find herself in the same fix as the characters she is reading about. Would we wonder about being in the circumstances of words on a page?

Death by Judgment

T

he second most common way to kill interest in literature is death by judgment. One faults or excuses author, character, or the society depicted according to the moral and social standards prevalent today, by which I mean those standards shared by professional interpreters of literature. These courses are really ways of inculcating those values and making students into good little detectors of deviant thoughts.

“If only divorce laws had been more enlightened, Anna Karenina would not have had such a hard time!” And if she had shared our views about [insert urgent concern here], she would have been so much wiser. I asked one of my students, who had never enjoyed reading literature, what books she had been assigned, and she mentioned Huckleberry Finn. Pondering how to kill a book as much fun as that, I asked how it had been taught. She explained: “We learned it shows that slavery is wrong.” All I could think was: If you didn’t know that already, you have more serious problems than not appreciating literature.

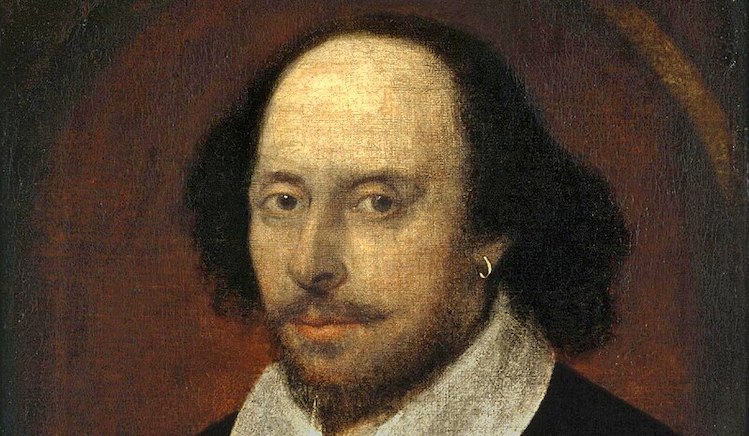

In this approach, the more that authors and characters shared our beliefs, the more enlightened they were. This is simply a form of ahistorical flattery; it makes us the wisest people who ever lived, much more advanced than that Shakespeare guy. Of course, numerous critical schools that judge literary works are more sophisticated than that class on Huckleberry Finn, but they all still presume the correctness of their own views and then measure others against them. That stance makes it impossible to do anything but verify what one already believes. Why not instead imagine what valid criticisms these authors would advance if they could see us?

What makes a work literary is that it is interesting to people who do not care about its original context. Literariness begins where documentariness ends.

Us. When intellectuals condemn what is wrong with “us,” they usually mean Americans without postgraduate degrees. This “us” is a strange use of the first person plural, for it excludes the speakers. It’s an us that excludes us. Perhaps we need a new grammatical category to designate it—let’s call it the “self-excluding we.” By the way, the “self-excluding we” exists elsewhere—for example, when parents talk to young children. “We’re having a little diarrhea today, aren’t we?”

If one does not allow other perspectives to show the limitations of our own, literature easily becomes pointless. In a real dialogue, new insights can emerge.

The Documentary Fallacy

O

ne can kill a work a third way: by treating it as a document of its time. “The author didn’t write in a vacuum, you know!” In other words, Dickens is notable because he depicts the deplorable conditions of workers of his age. True enough, but a factory inspector’s report might do even better.

This approach puts the cart before the horse. One does not read Dostoevsky to learn about Russian history; one becomes interested in Russian history from reading its classics. After all, every culture has many periods, and one can’t be interested in each period of every culture, so the argument about Russian history is bound to fail except with people already interested in Russian history.

What makes a work literary is that it is interesting to people who do not care about its original context. Literariness begins where documentariness ends. Dostoevsky illuminates psychological and moral problems that are still pertinent, even outside Russia.

A few years ago, when I was talking to a group of students, one of them asked why I teach the books I do, and I replied simply that they are among the greatest ever written. Later one of my colleagues told me she experienced the thrill one hears when a taboo is broken, because it has been orthodoxy among literature professors for some three decades that there is no such thing as “great literature.” There are only things called great literature because hegemonic forces of oppression have mystified us into believing in objective greatness, whereas intrinsically Shakespeare is no different from a laundry list or any other document. If this sounds exaggerated, let me cite the most commonly taught anthology among literature professors, The Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism. Its editors paraphrase a key tenet of the dominant movement called “cultural studies,” which has set the critical agenda:

Literary texts, like other artworks, are neither more nor less important than any other cultural artifact or practice. Keeping the emphasis on how cultural meanings are produced, circulated, and consumed, the investigator will focus on art or literature insofar as such works connect with broader social factors, not because they possess some intrinsic interest or special aesthetic values.

In other words, what used to be called masterpieces are worthy of study only insofar as they fit into a liberationist program, and no further. If elements of popular entertainment illustrate social forces better than Pope or Proust do, then they should (and sometimes do) constitute the curriculum. The language of “production, circulation, and consumption” is designed to remind us that art is an industrial product like any other and supports the rule of capital no less, and perhaps more insidiously, than the futures market.

In universities, this approach often leads to teaching documents instead of literature. Or perhaps cultural theory itself, taught pretty much without reference to the cultural documents in which it is supposedly grounded. Or perhaps second-rate literary works, which are a lot better than great ones either as documents or as providers of simple political lessons. At Northwestern, our engineering students have room in their schedule for perhaps two humanities courses, so—just think of it—a professor chooses to expose them not to great writers such as George Eliot or Jane Austen but to second-rate stuff or, still worse, some dense pages written by philosophers such as Jacques Derrida or Michel Foucault.

In each of these interest-killing approaches—the technical, the judgmental, and the documentary—true things are said. Of course literature uses symbols, provides lessons in currently fashionable problems, and can serve as a document of its times. The problem is what these approaches do not achieve.

They fail to give a reason for reading literature.

What Literature Is Good For

I

s there something one can learn from literature one cannot learn just as well or better elsewhere? There is an obvious proof that the great novelists knew more about human psychology than any social scientist who ever lived. If psychologists, sociologists, or economists understood people as well as George Eliot or Tolstoy did, they could create portraits of people as believable as Middlemarch’s Dorothea Brooke or Anna Karenina. But no social scientist has ever come close.

Still more important: Many disciplines can teach that we ought to empathize with others. But these disciplines do not involve actual practice in empathy. Great literature does, and in that respect its study remains unique among university-taught subjects.

When you read a great novel, you put yourself in the place of the hero or heroine, feel her difficulties from within, regret her bad choices. Momentarily, they become your bad choices. You wince, you suffer, you have to put the book down for a while. When Anna Karenina does the wrong thing, you may see what is wrong and yet recognize that you might well have made the same mistake. And so, page by page, you constantly verify the old maxim: There but for the grace of God go I. No set of doctrines is as important for ethical behavior as that direct sensation of being in the other person’s place.

Early in Anna Karenina, there is a remarkable scene in which Levin comes to propose to Kitty, who plans to refuse him. But when she sees him, she is shaken: “And then for the first time the whole thing presented itself in a new, different aspect; only then did she realize that the question did not affect her only—with whom she would be happy, and whom she loved—but that she would that moment have to wound a man whom she liked. And to wound him cruelly.”

Kitty puts herself in his position, feels for him, suffers the pain and humiliation he is bound to feel. This is how we know she is a good person. Kitty does what the reader is constantly invited to do. Empathy is not all of morality, but it is where it begins.

It is really quite remarkable what happens when reading a great novel: By identifying with a character, you learn from within what it feels like to be someone else. The great realist novelists, from Jane Austen on, developed a technique for letting readers eavesdrop on the very process of a character’s thoughts and feelings as they are experienced. Readers watch heroes and heroines in the never-ending process of justifying themselves, deceiving themselves, arguing with themselves. That is something you cannot watch in real life, where we see others only from the outside and have to infer inner states from their behavior. But we live with Anna Karenina from within for hundreds of pages, and so we get the feel of what it is to be her. And we also learn what it is like to be each of the people with whom she interacts. In a quarrel, we experience from within what each person is perceiving and thinking. How misunderstandings or unintentional insults happen becomes clear. This is a form of novelistic wisdom taught by nothing else quite so well.

Reading a novel, you experience the perceptions, values, and quandaries of a person from another epoch, society, religion, social class, culture, gender, or personality type. Those broad categories turn out to be insufficient, precisely because they are general and experienced by each person differently; and we learn not only the general but also what it is to be a different specific person. By practice, we learn what it is like to perceive, experience, and evaluate the world in various ways. This is the very opposite of measuring people in terms of our values.

To be sure, there are other disciplines that sometimes tell us we should empathize, but only literature offers constant practice in doing so. We follow the life of Dorothea Brooke or David Copperfield moment to moment, and we live with them for hundreds of hours, always living into their experience, growing along with them, approving or disapproving their choices, and perhaps changing our minds as they change theirs: This long process offers a lot of practice in empathy, enough to make it a habit. There is a big difference between inferring that someone else is humiliated or injured and knowing moment by moment what that feels like. But once we have the practice of that moment-to-moment feeling, we can infer what other people in real life are experiencing all the better.

It is even possible to empathize with our failures of empathy. That is one of Anton Chekhov’s key themes, where we feel from within why it is that people who are not fundamentally unfeeling often fail to consider the other person’s point of view. Chekhov’s story “Enemies” describes a doctor named Kirillov, whose son has just died, comforting his grieving wife as his face displays “that subtle, almost elusive beauty of human sorrow.” We empathize with him, not only for his grief over his son, but also because of his empathy for his wife. It’s a chain of empathy, and we are its last link.

Then the wealthy Abogin arrives to beg the doctor to visit his dying wife, and the doctor, with extreme reluctance, at last recognizes he has no choice. When they finally arrive, it turns out Abogin’s wife has only feigned illness to get rid of her husband long enough to escape with her lover. As Abogin cries and opens his heart to the doctor “with perfect sincerity,” Kirillov notices the luxurious surroundings, the violoncello case that bespeaks higher cultural status, and reacts wrathfully. He shouts that he is the victim who deserves sympathy because the sacred moment of his own mourning has been ruined for nothing.

Nothing makes us less capable of empathy than consciousness of victimhood. Self-conscious victimhood leads to cruelty that calls itself righteousness and thereby generates more victims. Students who encounter this idea experience a thrill of recognition. Kirillov experiences “that profound and somewhat cynical, ugly contempt only to be found in the eyes of sorrow and indigence” when confronted with “well-nourished comfort,” and he surrenders to righteous rage.

In this story, each man feels, justly, that he has been wronged by the other. And so neither receives the understanding he deserves. We empathize with both but also feel that they could have chosen instead to empathize with each other. But, as the author explains: “The egoism of the unhappy was conspicuous in both. The unhappy are egoistic, spiteful, unjust, cruel, and less capable of understanding each other than fools. Unhappiness does not bring people together but draws them apart.” That is still more the case when unhappiness makes us feel morally superior.

How to Teach

W

e all live in a prison house of self. We naturally see the world from our own perspective and see our own point of view as obvious and, if we are not careful, as the only possible one. I have never heard anyone say: “Yes, you only see things from my point of view. Why don’t you consider your own for a change?” The more our culture presumes its own perspective, the more our academic disciplines presume their own rectitude, and the more professors restrict students to their own way of looking at things, the less students will be able to escape from habitual, self-centered, self-reinforcing judgments. We grow wiser, and we understand ourselves better, if we can put ourselves in the position of those who think differently.

Democracy depends on having a strong sense of the value of diverse opinions. If one imagines (as the Soviets did) that one already has the final truth, and that everyone who disagrees is mad, immoral, or stupid, then why allow opposing opinions to be expressed or permit another party to exist at all? The Soviets insisted they had complete freedom of speech, they just did not allow people to lie. It is a short step, John Stuart Mill argues, from the view that one’s opponents are necessarily guided by evil intentions to the rule of what we have come to call a one-party state or what Putin today calls “managed democracy.” If universities embody the future, then we are about to take that step. Literature, by teaching us to imagine the other’s perspective, teaches the habits of mind that prevent that from happening. That is one reason the Soviets took such enormous efforts to censor it and control its interpretation.

We live in a world in which we more and more frequently encounter other cultures. That is part of what globalization means. And yet we are often baffled by them. Americans have the habit of assuming that everyone, deep down, wants to be just like us. It simply isn’t so, and I assure you that others assume that deep down we want to be just like them. When Russians listen to our leaders express their views about what people really want and how nations ought to behave, they think our leaders must be lying, because no one could actually think that way. They are as deeply convinced of the obvious correctness of their perceptions as we are of ours, and so they cannot imagine that others can sincerely perceive things differently.

But great literature allows one to think and feel from within how other cultures think and feel. The greater the premium on understanding other cultures in their own terms, the more the study of literature matters.

Because literature is about diverse points of view, I teach by impersonation. I never tell students what I think about the issues the book raises, but what the author thinks. If I comment on some recent event or issue, students will be hearing what Dostoevsky or Tolstoy, not I, would say about it. One can also impersonate the novel’s characters. What would Ivan Karamazov say about our moral arguments? How could we profit from the wisdom Dorothea Brooke acquires? Can one translate their wisdom into a real dialogue about moral questions that concern us—or about moral questions that we were unaware are important but in light of what we have learned turn out to be so? Authors and characters offer a diversity of voices and points of view on the world from which we can benefit.

Such impersonation demands absorbing the author’s perspective so thoroughly that one can think from within it, and then “draw dotted lines” from her concerns to ours. Students hear the author’s voice and sense the rhythms of her thought, and then, when they go back to the book, read it from that perspective. Instead of just seeing words, they hear a voice.

It is therefore crucial to read passages aloud, with the students silently reading along. Students should sense they are learning how to bring a novel to life. “So this is why people get so much out of Tolstoy!”

At that point, students will not have to take the author’s greatness on faith. They will sense that greatness and sense themselves as capable of doing so. Neither will they have to accept the teacher’s interpretation without seeing how it was arrived at or what other interpretation might be possible. No one will have to persuade them why Wikipedia won’t do.

Students will acquire the skill to inhabit the author’s world. Her perspective becomes one with which they are intimate, and which, when their own way of thinking leads them to a dead end, they can temporarily adopt to see if it might help. Novelistic empathy gives them a diversity of ways of thinking and feeling. They can escape from the prison house of self.