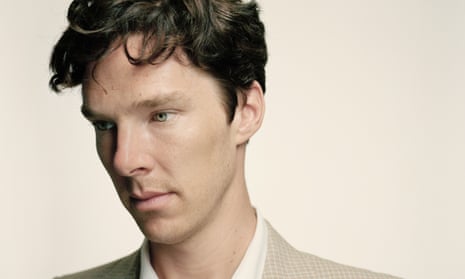

Twenty years ago, while he was still at school, Benedict Cumberbatch had his first chance to star in Hamlet. But, remembers Harrow drama teacher Martin Tyrell, he decided to concentrate on his A-levels instead. A couple of years earlier, the pupil had joined a Shakespeare workshop and had spent a couple of hours working on the play’s first scene. Tyrell remembers the 15-year-old being “so gripped by it. That was when he woke up to Shakespeare, I think, and the idea of becoming a professional actor.”

Tyrell, having seen Cumberbatch’s obvious talent in several school productions, thought he would become “an extremely hard-working, conscientious and successful professional actor, but I had no idea he would be both an Oscar nominee and an actor playing Hamlet to a sell-out audience months before it opened”.

In fact, Hamlet, due to open next week at London’s Barbican, sold out almost a year ago – in a matter of minutes. Few actors have had quite such a sudden leap in their career as Cumberbatch. His wasn’t even an “overnight” success – it was even faster. Within minutes of the BBC airing a new show by Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss in July 2010, in which Cumberbatch played a dazzlingly brilliant, sociopathic Sherlock Holmes set in present-day London, his name was trending on Twitter. The internet and social media took it from there: here was an unusual actor, in a show ideally suited to online obsessing about its plots, with fans eagerly writing filthy fan fiction about Holmes and Watson, encouraged by the chemistry between Cumberbatch and his co-star Martin Freeman.

Cumberbatch was then in his early 30s and had been working slowly and steadily for more than a decade, but in the five short years since Sherlock started, it seems as if he has been hurtling through life faster than anyone else: he has worked prolifically, won an Olivier award for Frankenstein at the National Theatre; an Emmy for Sherlock; been nominated for an Oscar, Golden Globe and several Baftas; and has generally been the subject of much global hysteria, not just from Sherlock superfans (last year one newspaper called him “this century’s Olivier”). He also got married, to the theatre director Sophie Hunter, and last month they had their first child.

Even though it came to him later than many of his peers, his fame can’t have been easy to get used to, though many who have met him say he hasn’t really changed. Actors often make dull interviewees, but Cumberbatch regularly comes across as interesting and unguarded, happy to talk about a wide range of issues. In 2013, when WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange admonished the actor for preparing to play him in The Fifth Estate, Cumberbatch said: “He accuses me of being a ‘hired gun’ as if I am an easily bought cypher for right wing propaganda. Not only do I NOT operate in a moral vacuum but this was not a pay day for me at all. I’ve worked far less hard for more financial reward. This project was important to me because of the integrity I wanted to bring to a provocative, difficult but ultimately timely and truly important figure of our modern times ... This resonated deeply with my beliefs in civil liberty, a healthy democracy, and the human rights of both communities and individuals to question those in authority.”

Sometimes, however, he gets it wrong: he apologised after referring to “coloured” actors, while making an otherwise valid point about the lack of diversity in film and television; and looked churlish by appearing to complain about being the victim of “posh-bashing”. But he has spoken about preserving his privacy and people trying to take pictures of him. “There are times when I’m completely fine with it and other times I’m, ‘Actually I’m with someone you’re totally ignoring and standing on while trying to get a photo of me, and this is not the right time,’” he said last year. “Then they walk away and I think, ‘God, am I an arsehole? Should I be accessible all the time?’ But I think, ‘Not really.’”

Cumberbatch had been around actors all his life: his mother, Wanda Ventham, and his father, Timothy Carlton, are actors; and many of their friends from the industry were around when Cumberbatch was growing up. For a while, their son had wanted to be a lawyer, but his talent for acting was obvious at school. Tyrell remembers a production of Georges Feydeau’s A Flea in Her Ear, and needing to cast one of the boys as “rather saucy and cheeky” French maid. “Someone said that a boy called Cumber-something might do, he’s very funny.” Soon afterwards, he played Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman “with such finesse and great intuitive talent, plus a kind of intellectual grasp which was a brilliant combination. I remember his parents hugging each other in the foyer and saying, ‘He is an actor.’”

One friend at Manchester University, where Cumberbatch studied drama, remembers him standing out – not just because he was one of the course’s “most brilliant” actors, but also “because he was very posh and seemed even posher in Manchester. He was like the exotic aristocrat, but always very humble and possibly a little embarrassed about the fact he’d been to Harrow.” He remembers Cumberbatch being part of a cool set, but also “really committed to acting so I don’t remember him ever being one of those ‘Let’s go and get smashed’ students”.

Penny Wesson, Cumberbatch’s first agent, took him on after meeting several teachers from Harrow at a Boxing Day drinks party. They all told her: “You should have seen our Benedict Cumberbatch, he’s going to be one of the great classical actors of his generation.” By that time, after Manchester and the London Academy of Music and Dramatic Art, Cumberbatch had been working as an actor, though under his father’s stage surname Carlton.

Wesson went to see him in a fringe production of the Friedrich Dürrenmatt play The Visit, loved him and asked to represent him. What did she like about him? “He has a presence. And also he is a pleasure to work with. He is a grown-up and was even back then.” She did, however, have one criticism. “I said, ‘You really should change your name back to Cumberbatch. It’s memorable.’”.

Wesson introduced Cumberbatch to Rachel Kavanaugh, who cast him in his first larger-scale productions of A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Love’s Labour’s Lost at the Regent’s Park Open Air Theatre in 2001; he appeared there again the following year, in Romeo and Juliet. For much of his 20s, he joked that he had played “big parts in small films, and small parts in big films”. There had been brief appearances in TV shows such as Spooks, Silent Witness and Heartbeat, but his first meaty small screen role was as Stephen Hawking in the 2004 BBC drama Hawking, based on the physicist’s student years at the time of his motor neurone disease diagnosis.

His first lead film role was in 2010’s Third Star as James, a young writer whos is dying, and goes on a last trip to Wales with three friends. Adam Robertson, one of the producers, says he fought for Cumberbatch to get the part (he was still a bit of an unknown quantity, and several backers had wanted a bigger name). “He was just perfect. You believed he was a writer, he had that kind of poetry. The first draft was quite dialogue-heavy and for Benedict it wasn’t an issue.” It had been for other actors, he says, who had hammed it up.

“He takes it very seriously,” says Robertson, who also starred in the film and shared a house with Cumberbatch and the other actors during the five-week shoot. One of the things he noticed was how interested he was in other people, their mannerisms, likes and dislikes. “He started drinking the kind of chai tea I was drinking,” he says with a laugh. “It’s like he goes round and sucks things up. That’s why he’s so good at the characters he plays, especially the ones who are biographical.”

Before Third Star, Cumberbatch had been popping up in critically acclaimed British films, but in supporting roles: as the pompous quiz team captain in Starter for Ten, the sinister businessman friend in Atonement, and as William Pitt in Amazing Grace. He spoke admiringly of other British actors, such as Michael Sheen and James McAvoy, and seemed to be still trying to find a place for himself. He definitely had something that took him beyond only character roles, but his unusual looks – the otherworldly angles of his bone structure and colouring – weren’t conventional leading man material. “He has Ingredient X,” says Wesson. “Someone who is not like anybody else. He’s not on anybody’s bandwagon.”

Sherlock changed everything. The director Susanna White had cast Cumberbatch in Parade’s End, Tom Stoppard’s adaptation of the Ford Madox Ford novels set during the first world war, when he was still a respected, but relatively unknown, actor. In the time it took them to raise the money to begin shooting, his career had exploded thanks to the sleuth. “It went from ‘Would this be someone acceptable to financiers?’ to ‘Is there any way we can get him? Can we get a window in his incredibly busy schedule?’” she says.

Stoppard already had Cumberbatch in mind for the part of the painfully repressed aristocrat Christopher Tietjens struggling with a changing world and a dysfunctional marriage. White shared his confidence. “You need a particular type of actor who can handle Tom Stoppard’s dialogue, who can take quite complicated writing and make it appear completely transparent and like normal conversation. It’s like someone who can do Shakespeare. I knew Benedict had the dexterity.”

She also needed an actor “who could convey enormous emotional layers without necessarily saying a lot. One of the things that drives Sylvia [Tietjens’ wife] mad is the fact he doesn’t talk about his feelings, he’s very silent, and I needed an actor who had tremendous power, who could convey a lot without a lot of lines. Benedict has got that charisma and intelligence. There is a real warmth. Although he was playing this very repressed character, you knew there was a place he could melt to with Valentine [the suffragette he falls in love with] that would feel very real. It was a complicated role and I knew quickly that he had all those qualities.”

On set, she says, he had tremendous energy and focus. “He likes to explore a scene, keep going at it and try it lots of ways. He’s really serious about what he does.” In life away from work, she says, “he’s one of those really generous, warm people. Maybe because it took him a while to get established, he really appreciates his good fortune now. So there is nothing starry or diva-y about him.”

Parade’s End aired on the BBC in 2012, and the following year, you couldn’t escape Cumberbatch. He was in blockbusters (Star Trek: Into Darkness and The Hobbit), and more interesting films, such as The Fifth Estate, and in 2013’s most talked-about and critically praised film 12 Years a Slave. The Imitation Game, which brought Cumberbatch an Oscar nomination for his portrayal of the mathematician and Enigma-cracking Alan Turing, came out in 2014, as well as a third series of Sherlock. Next year, after Hamlet, he will be Richard III for the BBC’s Hollow Crown series of Shakespeare’s history plays. But there have been quieter, less hyped productions, particularly for radio (more than 20,000 people applied for tickets to the recording of the last episode of the Radio 4 comedy Cabin Pressure, which had starred Cumberbatch since 2008).

He continues to make time for another Radio 4 drama, Rumpole, to the delight and relief of its director Marilyn Imrie. She had seen him on stage in 2010, in Terence Rattigan’s After the Dance, and realised he would be perfect as the young version of John Mortimer’s barrister. “I thought he was fantastic because he got that pre-second world war period absolutely right,” she says. “He had wisdom and dignity, and a certain heartlessless and incisiveness, which I thought was exactly right.”

Radio drama, she says, tends to be made at the last minute, with little time for rehearsal, but Cumberbatch “always comes prepared and thoughtful, having clearly understood where the nuances are and where he should speed up or take his time. I find him very directable, highly intelligent and he has that rare thing in a younger actor – he can summon up that quality of post-war Englishness that a lot of actors under 40 really can’t capture.”

She says he always seems to be looking for extra ways to enhance his performance – and remembers spotting him doing press-ups in the studio between takes. “I really admire actors who take everything about every aspect of their craft so seriously. Not all actors do.”

Cumberbatch’s range is impressive, and it is this, rather than the sharpness of his suits and cheekbones, that will sustain his career. He is comfortable as a period toff, but can also convincingly play the polar opposite, someone as contemporary and anti-establishment as Julian Assange. There have been geniuses, comedy turns and fantasy villains, with Sherlock a touch of all three.

“What matters to me is the quality and the variety of the work,” he said last year. “I’m in it for the long game. I’m interested in working in 40 years’ time, and turning round and talking to an actor and telling them stories about working with Judi Dench and Michael Gambon. So any talk of ‘man of the moment’ hype, heat, whatever, I just smile wryly. It’s the same shit with ‘sexiest whatever’. I was around 10 years before that as an actor and no one took the same face seriously.”

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion