Fighting back her tears, Gunita speaks into the telephone in Brent council’s customer service centre. “I’m sorry, I made a mistake. I was confused. I didn’t understand it was the only offer. Please, I’ll take the one-bedroom flat now,” she tells the housing officer on the other end of the line.

“It doesn’t matter now. You turned down a reasonable offer so I’m afraid we have no further duty towards you.”

As an anthropologist documenting the experiences of low-income tenants as they attempt to navigate London’s continuing housing crisis, I have become all too familiar with exchanges such as this. A record number of evictions is leaving increasing numbers at the mercy of local authorities. In cases like that of Gunita, where the applicant has turned down a property, councils can discharge their duty on the grounds that a “reasonable offer” has been made. In other instances, an individual may not even get as far as making a homelessness application: councils have become adept at discouraging them, a practice known as “gatekeeping”.

Increasingly tough frontline services are the result of the extreme pressures caseworkers are under to balance dwindling stocks of housing with the growing number of homeless people, say housing officers. As one put it: “If you’ve got thousands of people in temporary accommodation, and even more on the housing register, but only a few hundred properties, how do you play that?” Others say that staff cuts and the imposition of targets engenders a culture in which suspicion of those thought to be “playing the system” often takes precedence.

Real though these pressure are, the emergence of an institutional siege mentality inside councils also reflects a broader cultural trend – the resurgence of the idea that poverty is somehow an individual moral failing. While housing officers may feel that they are forced to be tough, in doing so they help to reproduce what is essentially a class war being waged on the poor. Evicted tenants are not to blame for the decimation of council housing, the deregulation of the private rented sector or the transformation of London into a prime investment hub for financial capitalism. But they are often made to bear sole responsibility for the social forces that act upon them.

Gunita’s story exemplifies this point. The mother of two 16-year-old boys, in 2006 she was housed in temporary accommodation by Brent council after leaving an abusive relationship (her name has been changed to preserve her anonymity). The two-bedroom flat she was placed in was managed by a housing association. It didn’t own the property, instead leasing it from the freeholder.

In 2011, a social worker brokered an informal shared custody arrangement with her ex-husband, meaning her sons would now divide their time between their parents’ respective homes. Critically, the boys’ child benefit and housing benefit payments were transferred to Gunita’s ex-husband. This meant that, even though Gunita was still the main emotional carer, in the eyes of the housing authorities she had essentially become a single person.

Gunita had always paid her rent, but in August 2015 she received an eviction notice from the housing association. The freeholder wanted to move the social tenants on so they could let the flat on the private market. Gunita made a homelessness application to Brent, and received a phone call from a caseworker asking her to view a one-bedroom property. She tried to explain that, with two 16-year-olds living with her half the time, one bedroom would be too small. “But he didn’t listen,” she says. “He just said: ‘You have to take this property. I know you are single because you are separated. Your boys are not living with you.’ I tried to explain that we are sharing custody, but he just said the same thing again and again.”

A few days later, Gunita received a letter stating that Brent would be discharging its duty towards her. Once the eviction had gone ahead, she would therefore need to find a place in the private sector. For someone receiving jobseeker’s allowance, there was little prospect of raising enough money for a deposit, even if she could find a private landlord who would accept a tenant in receipt of housing benefit. Now realising that she was facing street homelessness, Gunita’s mental health deteriorated dramatically.

This situation could have been avoided had the council offered Gunita a second chance. She accepts that she should have looked at the property, but is adamant that the ramifications of turning down an offer were never fully explained. Had she been properly advised, she could have accepted the one-bedroom flat and then applied for a transfer.

Fortunately, not everyone buys into this unforgiving culture of punishment. Shortly before she was due to be evicted, a local benefit claimants’ network called the Kilburn Unemployed Workers’ Group offered to help. KUWG is part of the London Coalition Against Poverty, a network of local groups who undertake what they call “direct action casework” in support of individuals facing problems with benefits and housing.

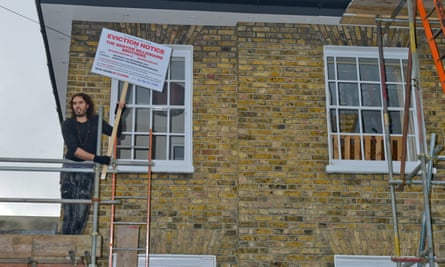

On the day of the eviction, KUWG members, many of whom are older people with physical ailments, gathered outside Gunita’s front door from 7am. In the freezing cold, the group played music, handed out leaflets and shared tea and biscuits. Their presence successfully discouraged the bailiff.

After a new possession order was granted in May, the group gathered outside for three days in a row in order to thwart the bailiffs. Eventually, lacking the capacity to carry out daily resistance, Gunita was evicted. When Brent’s housing review team upheld the original decision, a retired KUWG member offered to pay for a hostel. For one month, the only thing that kept Gunita from sleeping on the streets was an activist pensioner who, unlike Brent council, had decided that Gunita was owed a duty of care.

Gunita’s life was brought to the point of ruin by forces over which she had little control. In a moment of chronic housing shortage, it is much easier for housing officers to take a hard line and rid themselves of another case. But in doing so, they help to reproduce a system that allows landlords, property developers and financiers to routinely dispossess and displace the poor to further enrich themselves.

In order to solve the housing crisis, we need to fundamentally transform the political and moral culture that has allowed social policies and public services to be shaped by a divisive culture of punishment and suspicion. A burgeoning grassroots housing movement has begun this process, and groups such as KUWG offer glimmers of hope amid the myriad tragic cases. The urgent task now is to find ways of scaling up these fragments of resistance into lasting communities that can take collective responsibility for their constituents’ wellbeing.