August 22, 2017

Should Architects Work With Nature or Resist It?

Frank Lloyd Wright urged architects to work with nature. But as the planet warms, they may need to pursue a more defensive, “resilient” position.

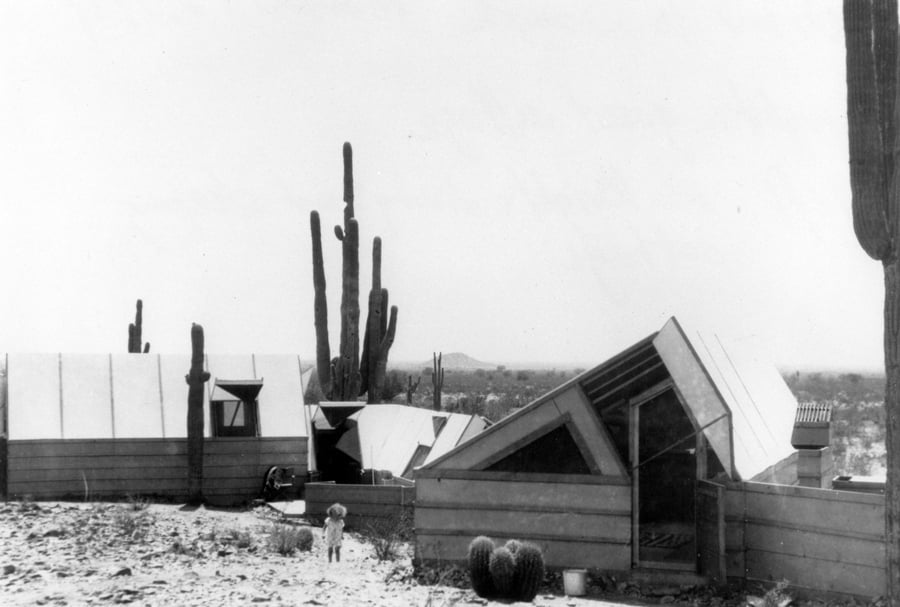

Courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Sometime in the early 1980s, Reyner Banham looked out across a stretch of Arizona landscape—a dry wash and long mound of earth scattered with trash. “[A]mong the chollas and cacti there are areas of burned ash, holes containing broken porcelain insulators and what may be pieces of toilet fitting, broken china and other domestic detritus; and areas of compacted ground that might have been the sites of small buildings,” he later wrote in Scenes in America Deserta as the opening to a chapter entitled “Frank Lloyd Wright Country.”

This ruin, Banham explains, was the site of a precursor to Taliesin West, the Ocatilla Desert Camp, a project the critic and historian considered one of Wright’s best projects for its ingenuity and as the root of Wright’s thinking on southwestern landscapes. Built in early 1929 as a base from which Wright and his team could develop San Marcos in the Desert, a luxurious resort, the camp’s low-slung board and batten structures were painted the color of the desert floor, then topped with canvas roofs, their corners brushed with scarlet to mimic the flaming blossoms of the ocotillo cactus. In the center of the compound sat a texture block model of the never-realized hotel.

Wright, forever the champion of an organic architecture suited to its environment, dedicated several pages in his autobiography to the thrall of the desert and Ocatilla. “All this impromptu effort, as you now see, is a human circumstance as appropriately ‘nature’ in Arizona as Arizona cacti, rocks and reptiles themselves,” he wrote.

While the architect saw his temporary structures as “desert ships” that would provide light structure and were strong against the wind and dust that blow across the landscape, Banham, although a fan, critiqued the architecture as ill equipped to deal with the heat and cold of the sunbaked mesa. He goes on to cautiously praise pueblo architecture for adobe’s inherent solar mass and to write that Wright’s experience at Ocatilla set the stage for his suburban (read unsustainable) visions of Broadacre City.

The camp itself was unsustainable; it was consumed by fire in June 1929, just a month after Wright and company decamped for Wisconsin. Still, elements from the project would reappear a decade later in Taliesin West. Wright’s winter outpost shows more insight into what we now call sustainable building practices. It uses “desert concrete”—a cured mixture made from sand and stones found on the premises—incorporates fireplaces, and was originally topped with light canvas enclosures. (The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation is testing new fabrics that would not only echo the original intent but also offer a more sustainable replacement to the aging acrylic now on-site.)

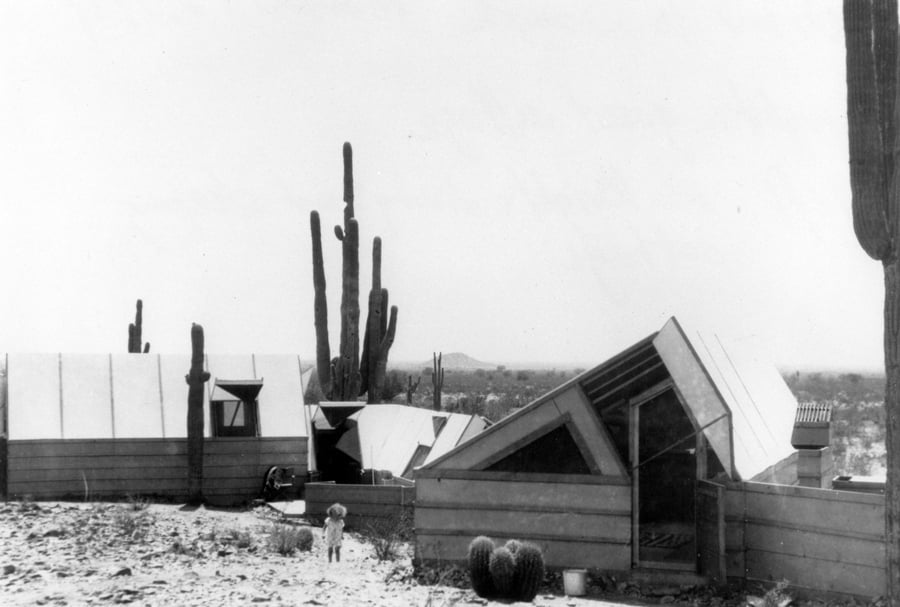

Courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

The gulf between Wright and Banham parallels the decades-long evolution of our understanding of environmentally responsive architecture. Although the sixties back-to-the-land builders shared Wright’s naturalist instincts, by the 1970s energy crises and the rise of conservation movements ultimately eclipsed such romantic notions. And there’s a second gulf, the one between Banham’s critique in the 1980s and now. Banham was concerned with the ecological appropriateness of the scale and function of the building. “But what is an architecture, great or small, that is proper to this arid zone?” he asks. Today, climate change demands a systems-scale response. New technologies promise to perform under extreme conditions and new terminology reflects the breadth of what’s at stake. Hence, our contemporary parlance: resiliency.

If Wright’s desert work offers up models of building with nature, resiliency as we’ve come to know it—robust earthquake structural assemblies and infrastructure to hold back rising tides—suggests that architecture resists nature. Resiliency comes with a preoccupation with architectural performance, as if technical prowess alone will preserve us from foreseeable damage. Yet history always reminds us that technology is unevenly distributed, and in places like the American Sunbelt, poorer communities often bear the brunt of natural disaster and environmental injustice. The benefits of green architecture make limited impact in neighborhoods that are lacking clean water and air. Perhaps we need to reconsider our concept of resilience as something other than a high-end catchphrase to be rolled out at global conferences.

For architect and historian Stephen Phillips, author of the new book on Frederick Kiesler titled Elastic Architecture, resilient architecture could have a different meaning. He floats the idea that it could be “passive aggressive” and points to a quote by William James, the philosopher whose thinking was instrumental in shaping Kiesler’s theories of elasticity and visionary designs like the Endless House. “Weak enough to yield to an influence, but strong enough not to yield all at once,” wrote James regarding the plasticity of our daily habits.

Applied to design, this idea of yielding—especially over time—captures what we might see as an inevitable need for adaptation in the face of climate change and limited resources. This doesn’t mean that architecture is literally elastic, as with Kiesler’s Space House (featuring sponge rubber carpets, according to Phillips’s text). Those fanciful proposals rarely see functionality. But yielding counters the conceit that architecture is appropriate, to use Wright’s term, in every circumstance.

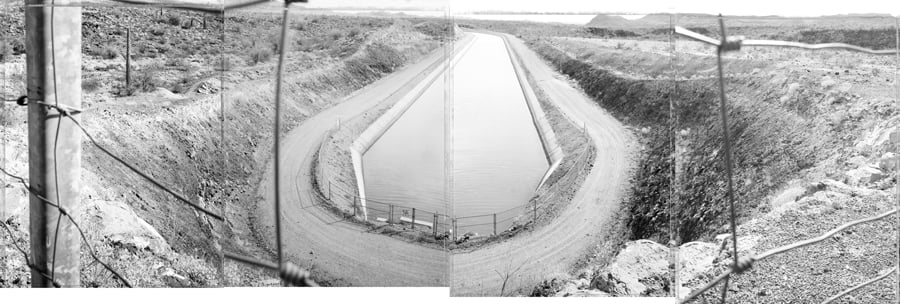

Courtesy © Peter Arnold

Jason McLennan, architect and creator of the Living Building Challenge, notes that in ecology, resiliency is the “carrying capacity” within an ecosystem. The desert, he explains, begins with an impoverished load: There’s limited water and top-soil, unrelenting UV, high temperatures, cold night conditions. “There’s not a ton of big mammals, not a lot of life,” he notes. “But after a rain, the dry riverbed comes to life for a few weeks, then retreats. To build with nature, first you need to recognize that there is a point you cross when there is too much.”

Although McLennan cautions that humans are not outside finite resources, he sees limits as generative to design. “A psychological change happens when you think you are above limits: You’re careless, wasteful; your own creativity is limited and you end up with solutions that diminish the quality of the experience. Designers are not taught in design school about the notion of limits. They are not taught to work with what you have—the climate, weather, and other life-forms impacting their designs.”

As cofounder of the Arid Lands Institute (ALI), designer and educator Hadley Arnold has spent plenty of time working in the Southwest, researching and observing desert water resources and asking students to design responses to findings. But these days she and partner Peter Arnold are crunching water data. Their office is inside the Los Angeles Cleantech Incubator (LACI), a nonprofit space underwritten in part by the city that is filled with start-ups and others at the intersection of eco and urban, such as CicLAvia and River LA (the organization that hired Frank Gehry to study the Los Angeles River).

The ALI and collaborative partners are at work building Hazel, a digital design tool that models hydrologic, social, and economic data. In bringing together varied inputs, their aim is “to support and accelerate water-smart planning and design in drylands.” ALI’s first test case is Los Angeles, but eventually Hazel will enable designers across arid communities to address water infrastructures. The implications toward a responsive architecture are not lost on the profession. The AIA College of Fellows awarded the project the Fellows Latrobe Prize in 2015. Resiliency for Hadley Arnold is about getting away from what she sees as a commercialized market for crisis architecture and giving designers the ability to make better decisions.

Sitting at a table in a generic conference room, Arnold flips through a glossy volume of Wright’s drawings. She stops at an ink and pencil perspective of the unbuilt San Marcos resort—the project that enabled his Ocatilla Desert Camp. An arroyo runs through the center of the site, bridged by Wright’s elaborate design. He had intended to harvest the water in the dry wash for pools and fountains. Arnold chuckles at Wright’s idea. In the desert, you’re taught to stay away from washes, which flash flood in a storm. The last place you want to build is in an arroyo. His unresilient attempt to design with nature only heightened the need to resist its consequences.