Senior Editor

- FMA

- The Fabricator

- FABTECH

- Canadian Metalworking

Categories

- Additive Manufacturing

- Aluminum Welding

- Arc Welding

- Assembly and Joining

- Automation and Robotics

- Bending and Forming

- Consumables

- Cutting and Weld Prep

- Electric Vehicles

- En Español

- Finishing

- Hydroforming

- Laser Cutting

- Laser Welding

- Machining

- Manufacturing Software

- Materials Handling

- Metals/Materials

- Oxyfuel Cutting

- Plasma Cutting

- Power Tools

- Punching and Other Holemaking

- Roll Forming

- Safety

- Sawing

- Shearing

- Shop Management

- Testing and Measuring

- Tube and Pipe Fabrication

- Tube and Pipe Production

- Waterjet Cutting

Industry Directory

Webcasts

Podcasts

FAB 40

Advertise

Subscribe

Account Login

Search

How data has evolved in structural fab

A Wisconsin structural fabricator exemplifies the industry’s data transformation

- By Tim Heston

- January 28, 2019

- Article

- Manufacturing Software

If someone returned after 10 years away from Endres Mfg. Co.’s shop floor, they would see a different layout, a few new machines, but nothing dramatic. But if he started working there, he’d quickly realize that information flows in a completely different way.

“We’re making the hay while the sun is shining, and we feel it’ll shine brightest through 2019.”

So said Randy Herbrand, chief operations officer at Endres Mfg. Co., a structural fabricator in Waunakee, Wis., that has profited from a construction boom in the area. The 87-employee company added another fabrication shop and has hired another 25 employees just within the past year. The company continues in its unusual, charming Bavarian campus, designed in the 1960s to reflect the Endres family’s German heritage. If you didn’t read the sign, you wouldn’t think the place churned out structural steel.If someone who left the business 10 years ago, just as the Great Recession took hold, and returned to see the activity on Endres’ shop floor today, they’d be happy to know the business has survived and thrived. Still, that person would see a different shop floor operation. The structural fabricator has embraced more automation, but the starker difference is in the flow of information. Buildings are still made of steel, but the 1s and 0s of digital data are now the lifeblood of how projects move from one stage to the next.

Data Flow a Decade Ago

Herbrand recalled seeing his boss come through the door on Monday morning with a few rolls of prints, all the awarded projects. He’d set them down on the detailer’s desk and ask them to detail the projects in a few weeks, with anchor bolts available in about a week.

The detailer would detail the project, print the drawings, and send them out for approval via UPS. The drawings would return in a few weeks, sometimes a month later. “[The drawings] would again go to my boss’s desk, and he’d give it back to the detailer, and tell them to get them cleaned up for the shop,” Herbrand said.

The detailer would clean up the drawings, print the documents, and hand them to the production manager, who would prepare the project and distribute the work. Herbrand continued, “Once [the production manager] had it ready for the shop, that was really the first time the fab shop communicated with the general contractor.”

At that point the job went into production, with any expedited items broken out separately. Fabricators and people in the parts department physically took the prints and checked a check sheet to confirm the work they performed. The welders retrieved parts they needed from the parts department, and work made its way through the shop.

After parts emerged from the final process—be it grinding, painting, or anything else—shipping department workers again used a handwritten list to check off all the members as they prepared them for the truck. Paper and pencil still ruled the day.

“[When members were prepped for the truck] was really the first time we had a really firm grasp of how much a particular project was completed,” Herbrand said, “when they were actually loading the truck for the next day. That’s funny to think about now, but it just shows how different times were just a decade ago.”

How Information Flow Evolved

When the fabricator wins work today, it’s assigned to a project manager. “And immediately we have many conversations with the contractor,” Herbrand said, “after which very specific batches of material get released for fabrication. And overall everyone has a much better understanding of project scheduling.”

Underlying all this is the company’s move from a manual, paper-based work flow system to one that’s managed by software—in this case, FabSuite. When a workstation is ready to work on a project, the operator pulls the CNC files from the management software, which has the specific batch on the schedule called out, organized, and ready. The shop’s PythonX plasma cutting system processes the main members and a system from Controlled Automation processes the flat bar and angle. Once a batch is completed, the parts department delivers the necessary components to the fabrication area.

That parts department is organized in “grocery store” fashion, categorized and organized for easy retrieval. After a quick glance at the parts inventory, anyone in the shop should know where a job stands in fabrication—a live “percentage completion” indicator for an order. Quality control verifies the percentage completion, at which point the parts that require coating move on to the paint room. In shipping, workers perform a final checkoff before loading the project on a truck.

No More Math at the Saw

A decade ago saw operators did their own nesting. They’d receive a cut list, sit down for 20 to 30 minutes, do the math, and nest that project in the most efficient way possible out of the material they had at hand.

In fact, Herbrand recalled that the saw operators would achieve extremely high material utilization—much higher, sometimes, than software would be able to accomplish at a push of a button. “But you have to value that time,” Herbrand said, “and if you’re not going to value that time, it’s not a fair comparison.”

Now employees retrieve the correct heat number, mount it in the saw, enter the part numbers into FabSuite, and with that, the main members are nested automatically. Material utilization may not be quite as high as it was on all members, but the time savings from automated nesting more than makes up for it.

Proactive Sequencing

Sometimes the cut lists have parts for various jobs; other times the list may have various parts for one job but for different sequences (that is, truckloads delivered at different times to the same job). And at Endres, the sequencing has changed significantly during the past 10 years, thanks in part to building information modeling (BIM) software.

Historically, Endres had the headaches that many structural fabricators experience. It received the erection plans for a project along with the detail drawings, and out would come the fluorescent markers. Planners pored over the plans until they had drawn a rainbow of colors, each signifying a sequence.

After fabrication, material would be weighed as it was loaded onto the truck, and when capacity was reached, the truck pulled away. Planners on-site knew roughly what they were getting and when, but they didn’t have a detailed picture.

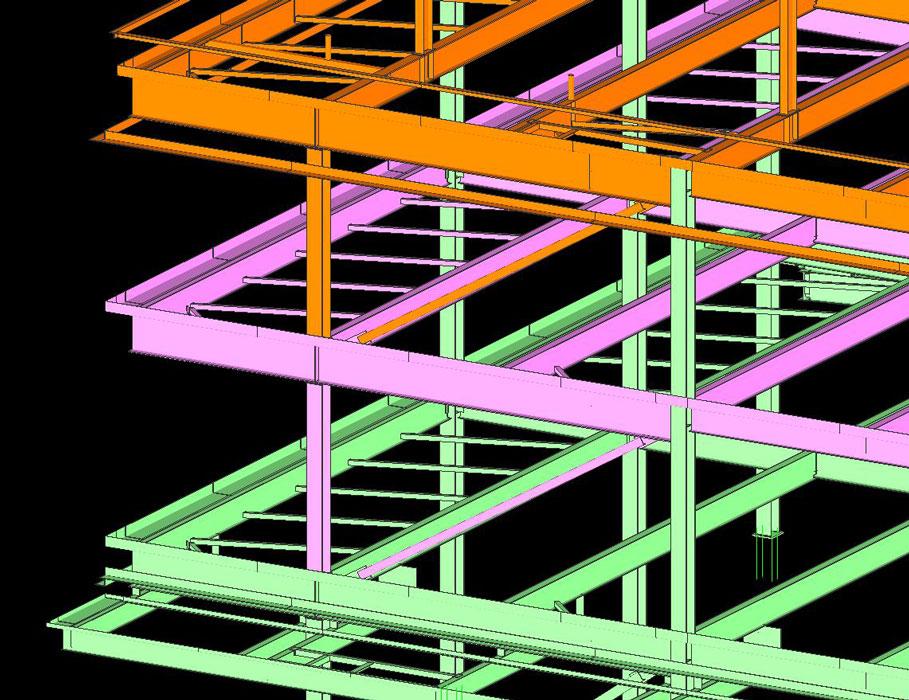

Today they have a detailed plan not just days in advance, but weeks and sometimes months, before the actual steel arrives on-site. Within the SDS/2 BIM platform, the Endres project manager builds the sequences as the work gets released to the shop, then gives the appropriate information, including the member list and all the associated reports with that sequence, to the right people.

“That has paid huge dividends,” Herbrand said, “because we can share that model easily with someone in the field. For instance, we can send a 3D PDF that’s color-coded, and someone in the field can manipulate it with his fingers using a tablet.”

Endres shares this sequence model with contractors, who receive it as a 3D PDF. Color coded, the model shows contractors exactly what structural members will arrive at the job site, and when.

Each color represents a build sequence, so those in the field know exactly what will be arriving and when. Sequences are scheduled and placed into the shop in the optimal order, so that completed work reaches the truck at just the right time. And because those on the job site know exactly what they’re getting and when, they can request changes very late in the process.

Of course, sooner is always better, which is why the sequencing information is shared early on in the project timeline. But flexibility in the structural fabrication supply chain has become a key asset for success.

Flexibility has become especially critical when dealing with all the uncertainties of urban job sites. For instance, a road might be closed for construction, which would force a crane to move to the opposite street to pick members—and being on the opposite side, it now needs different members. If the general contractor knows this ahead of time, he can communicate directly with Endres, change the sequencing, and the shop schedule adapts.

More generally, adaptability helps meet the needs of other parties who join later in the project timeline. “Typically, when you start a job, we’ll try to get it sequenced as best we can with who’s onboard at the general contractor,” Herbrand said. “But as the job progresses, you’ll get the ironworkers and foreman onboard, and they might say, ‘We’re going to use a different crane approach.’ So they mark [the PDF], indicate changes, and send it back to us. And it’s now so much easier, because we’re now speaking the same language. It used to be so much more cumbersome.”

The Right Information Changes Everything

When people outside fabrication think about the modern shop floor, they think about robotics, big machines, touchscreen controls, and more. And Endres has certainly upgraded its fabrication machinery. But as Herbrand explained, having the right, complete information at the right time has made all the difference in the world.

A decade ago a contractor could look at a framing plan and expect a delivery of fabricated members for, say, a specific wing of a building. But just by looking at the paper plan, he couldn’t tell exactly which fabricated members he’d be receiving that day—and for good reason, because the structural fabricator didn’t know exactly, either, until the truck was completely loaded.

When it came to the delivery schedule back then, Endres (along with other structural fabricators) didn’t give the contractor a lot of options, simply because options require detailed, real-time information—something no one really had.

Herbrand recalled scanning and emailing or, quite often, hand delivering a marked-up plan set showing the contractor what would be delivered and when. It could take three weeks to mark up a plan set, send it to the contractor, then get feedback. “Now we can do all that in minutes.”

Perhaps more than anything else, this free flow of information has allowed the structural fabricator to produce five times the volume it did a decade ago—without breaking a sweat.

About the Author

Tim Heston

2135 Point Blvd

Elgin, IL 60123

815-381-1314

Tim Heston, The Fabricator's senior editor, has covered the metal fabrication industry since 1998, starting his career at the American Welding Society's Welding Journal. Since then he has covered the full range of metal fabrication processes, from stamping, bending, and cutting to grinding and polishing. He joined The Fabricator's staff in October 2007.

subscribe now

The Fabricator is North America's leading magazine for the metal forming and fabricating industry. The magazine delivers the news, technical articles, and case histories that enable fabricators to do their jobs more efficiently. The Fabricator has served the industry since 1970.

start your free subscription- Stay connected from anywhere

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Fabricator.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Welder.

Easily access valuable industry resources now with full access to the digital edition of The Tube and Pipe Journal.

- Podcasting

- Podcast:

- The Fabricator Podcast

- Published:

- 04/16/2024

- Running Time:

- 63:29

In this episode of The Fabricator Podcast, Caleb Chamberlain, co-founder and CEO of OSH Cut, discusses his company’s...

- Industry Events

16th Annual Safety Conference

- April 30 - May 1, 2024

- Elgin,

Pipe and Tube Conference

- May 21 - 22, 2024

- Omaha, NE

World-Class Roll Forming Workshop

- June 5 - 6, 2024

- Louisville, KY

Advanced Laser Application Workshop

- June 25 - 27, 2024

- Novi, MI