A while back I was given a short book by Marc Baer, Mere Believers: How Eight Faithful Lives Changed the Course of History (HT JP). Marc Baer is a Professor of History at Hope College. His specialty is modern British history. In this book he looks at eight Christians in Britain examining how their lives, inspired by Christian faith, made a difference. The individuals range from Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon (1707-1790) to Dorothy Sayers (1893-1956) spanning some two and a half centuries. In between we find Olaudah Equiano, kidnapped in Africa, enslaved, freed, and a voice for the humanity of Africans in Britain, Hannah More an author and reformer, as well as the more well known William Wilberforce, Oswald and Biddy Chambers, and G. K. Chesterton. The mix of men and women is intentional – and the women were active in preaching, teaching, shaping, and building. No mere supportive role here.

All eight of these individuals were committed orthodox Christians. Not evangelicals or fundamentalists, but converted and committed nonetheless. Selena Hastings practically formed her own denomination, the others are of Methodist, Anglican, Baptist, and Roman Catholic persuasions. Several of them experienced a clearly documented “conversion” of some sort, and this experience was transforming. In other cases there is little evidence for an abrupt conversion, rather a gradually maturing faith.

The book is well worth reading, and designed for small group study – especially appropriate for younger adults perhaps, but of value for all of us. Each chapter includes a set of discussion questions.

Today I would like to focus on one theme Baer brings out in the book – the importance of work as a Christian calling. Every Christian is called to make a difference through their life and work. There are not professional Christians (pastors, evangelists, missionaries, seminary professors, …) and then the rest of us – with an ordinary job or vocation, but not a Christian calling.

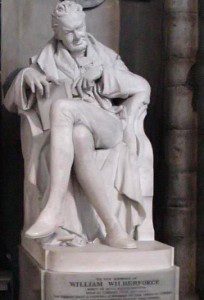

William Wilberforce, for example, entered politics as a young man elected to the House of Commons at 21. His conversion experience was a number of years later. He then wondered if politics where he should direct his efforts.

William Wilberforce, for example, entered politics as a young man elected to the House of Commons at 21. His conversion experience was a number of years later. He then wondered if politics where he should direct his efforts.

Withdrawing for a season of prayer and reflection on his vocation, Wilberforce considered a career change, including becoming a clergyman, but was persuaded by Newton that his calling was to serve God through politics “that the Lord has raised you up for the good of the nation.” … And so Wilberforce entered into his diary: “My walk is a public one. My business is in the world; and I must mix in the assemblies of men, or quit the post which Providence seems to have assigned me.” …

The public walk, the mixing in the assemblies of men may look secular, but was as spiritual – perhaps in his case more so – than had he become a pastor. Contemporaries dubbed Wilberforce and his allies “the Saints,” recognizing, not always in a complimentary fashion, that the motivation for their actions lay beyond political office or power for its own sake. Thus when Wilberforce stood on the floor of the House of Commons, he was on holy ground. Signifying his own sense that politics was his vocation, he set the highest standard for himself: “A man who acts from the principles I profess reflects that he is to give an account of his political conduct at the judgement seat of Christ. Accountability became one of the hallmarks of his public life. (p. 69)

Baer outlines four aspects of his approach that helped Wilberforce toward this aim of integrating public, private, and Christian life. (1) He had a close network of friends “to whom he might open his heart and who in private confronted him regarding his faults.” (p. 70) (2) He embraced philanthropy. After his conversion and before his marriage he would give away 25% of his income. Philanthropy marked his entire life. In his own words: “When summoned to give an account of our stewardship, we shall be called to answer for the use we have made of relieving the wants and necessities of our fellow creatures.” (p. 71) (3) Believing in the power of ideas to change society he devoted much time and effort to his writing. (4) He stood for what was right, not necessarily with his friends. This hurt him politically – he would side with the opposition when they were right and this wasn’t popular among politicians then as it isn’t popular today. Wilberforce also persevered with what was right and in the end achieved the passage of a bill ending the British slave trade.

Five lessons can be drawn from the life of Wilberforce.

(1) “Following his conversion as he grew older Wilberforce’s sense of calling grew deeper and deeper – despite discouragements.” (p. 80)

(2) “[E]vident in Wilberforce’s life was his biblical rootedness combined with a deep personal faith in Christ. He was willing to pay the price for his politics because he knew Christ had paid the ultimate price for Wilberforce.” (p. 81)

(3) The importance of teamwork. This requires genuine humility and appreciation for the efforts of others. Pride is the greatest stumbling block.

(4) “Wilberforce’s persuasion and action was out of his whole mind – he was not a fanatic but a well rounded human being.” (p. 82)

(5) “Wilberforce was uncompromising on principles, but flexible on tactics – hence the strategic partnerships that characterized his public career.” (p. 83)

Work as a calling is also defines the chapters on Oswald and Biddy chambers, G. K. Chesterton, and Dorothy Sayers.

Oswald Chambers ended his life and work in a more traditional “Christian calling” as a bible teacher and a chaplain in Egypt during WWI. However, he started as an artist.

To Oswald the arts were from God: “Music, Poetry, Art, through which God breathes/ His Spirit of Peace into the Soul.” (p. 88)

In a letter to a friend he wrote:

“Whom shall I send to proclaim the salvation of the aesthetic kingdom, who will go for us?” Then through all me weakness, my sinfulness and my frailty my soul cried “Here I am, send me.” I would as soon drown myself as undertake such a work unless He was with me, unless He called me, unless He sent me.” (p. 88)

The allusion is to Isaiah 6. Chambers was “fully convinced concerning the integration of all spheres of culture creation.” (p. 89) Thus, human vocations should be driven in one fashion or another by Christian calling. And there must always be an openness to change – moving into a new direction.

Rather like Hannah More, God called Chambers from focusing on his gifts in art, poetry, music, and philosophy (which Chambers hoped would provide a livelihood), to a vocation that would employ those gifts but in his case never provide a secure income, quite unlike More’s situation. The comparison reveals that there is not one pattern among believers and based on the two Chambers, not one trajectory within a single believer’s life. (p. 94)

Chambers emphasized the importance of all aspects of life and Baer, in turn, emphasizes the importance of this approach for us today.

Chambers is then the model for the modern believer. Those of us who emphasize “just believe” ought to heed his challenge to cultivate our minds; those of us who privilege thinking at the expense of the emotional life need to spend some time introducing the left side of our brain to its ally, the right side. (p. 96)

G.K. Chesterton was an author and had a long career as a journalist. He was “a truth-teller in an age of false prophets. He used his skills as a writer and a journalist to confront and combat the modernistic trend toward eugenics that swept Europe and North America in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. It is hard for us today to really appreciate this power of this movement. The atrocities of WWII changed so much. But many eminent people were on board with the ideas in the era before the wars. The US Supreme Court upheld 8-1 a law allowed for enforced sterilization of the less fit. Chesterton dedicated much of his effort toward the topic of eugenics.

[H]is campaign against eugenics was an important element of Chesterton’s stand against the spirit of his age and for orthodox Christianity as the antidote to modernist ideologies. Because the debate over eugenics vexed Chesterton intellectually and morally – as a bad idea that would lead to bad ethics – in Eugenics and Other Evils Chesterton proposed a revolutionary response to the danger at hand: “we are already under the Eugenist State; and nothing remains to us but rebellion.” For Chesterton, revolution was defined as turning back to recover the things lost. This “turning back” is what believers understand by repentance. (p. 134)

Chesterton made a difference, and we continue to read his work today, although not so much on eugenics, as this is no longer the same pressing issue.

Dorothy Sayers. “The only Christian work is good work well done.” Sayers is the final example in the book. None of the examples in the book lived entirely exemplary lives and Sayers is no exception. (The Chambers may have come the closest.) Sayers wrote extensively on the importance of work. It permeates her last Peter Wimsey books (Gaudy Night and Busman’s Honeymoon). She was a poet, scholar, social critic, theologian, essayist and devout Anglican.

Sayers confronted the banality that Christianity was essentially about how one felt rather than what one thought, countering that it was “hopeless to offer Christianity as a vague, idealistic aspiration: it is a hard, tough, exacting, and complex doctrine steeped in drastic uncompromising realism.” In terms of creative artists like her, Sayers believed inadequate thinking produced mediocre art: “A loose and sentimental theology begets loose and sentimental art forms; an illogical theology lands on in illogical situations; an ill-balanced theology issues in false emphasis and absurdity.” By extension her tough-minded approach applied to all work by hand or mind, hence her challenge to us: think about how we might cultivate a sacred understanding of work, and it will change forever how we comprehend what we do. (p. 140)

Baer’s summary of the theology of work derived from Sayer’s writing should be required reading for young (and old) Christians . Just one example:

With a right understanding of work, the misconception disappears that the most spiritual vocation for a Christian is becoming a missionary or pastor, therefore validating all types of work humanity has at its fingertips. Engage in creative, lively, fulfilling work. Work, and work well. It is what the Creator created you for. (p. 154)

This is true of artisans, builders, professionals, janitors … everyone, everywhere.

Overall a thought provoking book that should promote invigorating and constructive conversation. It certainly set me to thinking about how what I can do with my talents, abilities, education, and passions might do to make a difference.

I’ll finish with one of Baer’s questions and add a few of my own.

How might better comprehending work help us understand who we are as humans?

How might a better understanding of Christian calling help us fulfill our God given role as his image bearers?

Is pastor, teacher, missionary the ultimate in Christian calling?

If you are not a “professional” Christian, how does your work integrate with your Christian calling?

If you are a pastor, teacher, missionary, what do you do to enable others to follow their calling?

If you wish to contact me directly, you may do so at rjs4mail[at]att.net

If interested you can subscribe to a full text feed of my posts at Musings on Science and Theology.