Unscrupulous attorneys prey upon immigrants held in federal detention, advocates say

It was only too easy for legal assistant Hector Alfonso Sanchez to pose as an immigration lawyer and solicit clients locked up in federal detention.

Sanchez traveled from his office in San Antonio to detention centers across the country to interview immigrants and accept payment, according to the Texas Attorney General’s Office, which earlier this year secured an injunction barring him from advertising, performing or accepting money for immigration consulting services. Sanchez also had to pay restitution to clients, civil penalties and attorney’s fees.

The Sanchez case highlights what immigrant advocates say is a persistent shortcoming at immigration detention centers, especially those holding families — poor legal representation.

There is no guarantee of counsel in immigration court, and although groups of pro bono attorneys have been organized to represent migrants, opportunists have exploited immigrants desperate for help, advocates say.

“It’s a really ugly system,” said Elanie Cintron, a Denver-based immigration attorney. “They’re preying on the most vulnerable populations.”

It’s a population that continues to grow, especially as more families are caught crossing the U.S.-Mexico border illegally this year, their journeys driven in part by escalating violence in Central America.

From last October to July, 58,720 family members were caught crossing the southern border — nearly twice the number as the same time last year, according to U.S. Customs and Border Protection figures.

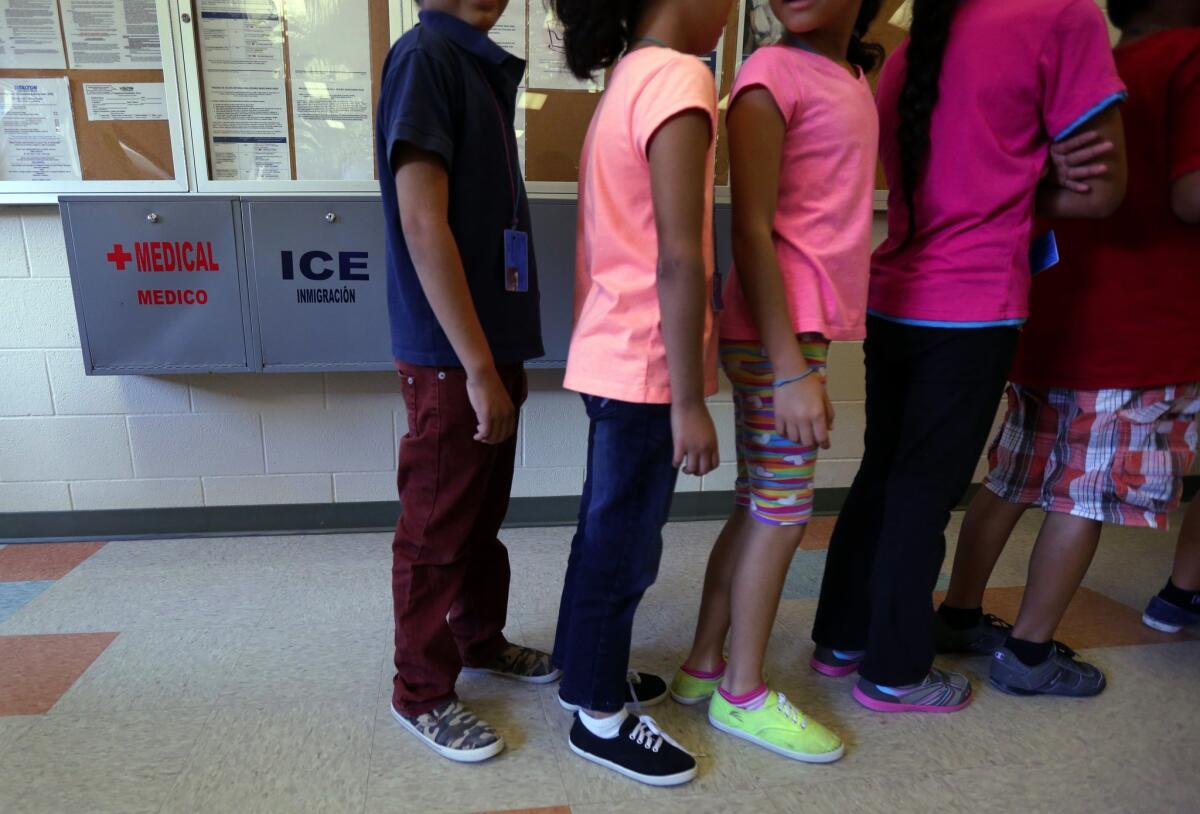

As of this month, 2,062 of those adults and children remained in family detention.

In order to represent those families and practice in federal immigration court, a lawyer must register online, be eligible to practice law, and be a member of the bar in good standing.

But officials at immigration courts, which are part of the Justice Department, do not screen lawyers. They discipline them — more than 1,500 since they took over the disciplinary program in 2000 — but mostly after lawyers have already been disciplined, convicted or pleaded guilty in other courts to serious crimes, according to Justice Department spokeswoman Kathryn Mattingly.

Those disciplined by immigration courts this year include:

• Vanessa Bandrich of New York, disbarred after she was investigated by the FBI and convicted of immigration fraud for assisting asylum applicants in concocting fake tales of persecution.

• Hector Cavazos Jr. of Stockton, suspended for 18 months, about six months after the California State Bar filed to suspend his license for three years and recoup $11,000 for four clients for having allowed his father to practice law out of his office without a license. In June he was disbarred by the state.

• Samuel Escamilla of Denver, suspended for three months after Colorado officials investigated him on accusations of taking clients’ money without working their cases.

Problems with private attorneys at family detention centers started soon after the Obama administration began expanding the centers in summer 2014, opening a temporary facility in Artesia, N.M. It was in Artesia that Michael Carrasco, of Carlsbad, N.M., was caught practicing law without a license — but only after Cintron and other pro bono lawyers complained, having gathered statements from his clients.

Carrasco already had been disbarred in New Mexico by the state’s Supreme Court in 2002, Cintron noted, but “he was going and using somebody else’s name. We were gathering declarations from women … I went to a room to talk to women who had spoken to him and 10 hands went up.”

Carrasco was disbarred again, this time by federal immigration court officials, a year ago. Cintron said the case illustrates the vulnerability of immigrant families in detention.

Some immigrants do not have the time or know-how to vet an attorney, or are unable to meet with a pro bono attorney or advocate who can guide them.

“When things move so quickly and we can’t get to those women in their cells to explain the system to them and someone tells them, ‘Oh, my cousin got this lawyer,’ then they just call whatever phone number they have,” Cintron said.

She said one of her clients, Celina Gutierrez-Cruz, 22, a Honduran detainee, was unaware that her previous attorney had a disciplinary record when she hired him.

The attorney, Gary Ortega of Brownsville, Texas, had been publicly reprimanded by the Texas State Bar in 2009 for misconduct after a grievance was filed against Ortega for allowing an employee of his to solicit a prison inmate as a client. In 2007 he had been disqualified and removed from a murder case in which his former client was convicted and sentenced to die. The case was appealed based on ineffective assistance of counsel.

Gutierrez-Cruz’s family paid Ortega $3,250 in March of this year based on assurances from his staff that she would be released on bond, Cintron said. The going rate to handle bond hearings is about $1,000, she said, although some private attorneys charge up to $5,000.

Gutierrez-Cruz’s family was not aware that because she had been deported in 2013, she was ineligible for bond. Cintron said Gutierrez-Cruz never signed a contract, received court paperwork, or spoke with Ortega in person or by phone before her bond hearing May 29.

Gutierrez was denied bond, and Ortega’s staff stopped contacting her, said Cintron, whom Gutierrez-Cruz was referred to through the CARA Family Detention Pro Bono Project.

“This was the one case that we caught. I always worry about the women we never get to see. What happens to them?” Cintron said.

Ortega did not return calls or emails.

Cintron and immigrant advocates also share the story of Lillian Oliva Bardales, a 19-year-old from Honduras.

Bardales has filed to reopen her asylum case, alleging the San Antonio attorney she paid $1,500 failed to prepare her to appear before an immigration judge, failed to outline the basic chronology of her case for the judge, and then failed to follow up with her when, upset about conditions in detention and facing deportation, she attempted suicide in detention June 3, 2015 — slashing her wrist with an ID bracelet.

“He did not do any work to prepare her for her hearing. Zero trial preparation — didn’t even direct the judge as to why she qualified for asylum,” said Bardales’s new pro bono attorney, Bryan Johnson.

Johnson, who is based in New York, who in his motion to reopen her appeal that attorney Miguel Vela’s negligence also harmed Bardales’s 4-year-old son, Christian, who was deported with her June 9, 2015.

“His past negligence was basically the basis of my motion to reopen her appeal,” Johnson said.

Vela, who is based in San Antonio, has not responded to the allegations in the appeal, and did not return calls or emails.

After her deportation back to Honduras, Bardales stayed in Tegucigalpa for about four months, working as a housekeeper and hiding from her son’s father, who she said had beaten and threatened to kill her.

“I thought the U.S. government would protect me,” she said in an interview, “Instead, they made my life worse.”

I thought the U.S. government would protect me. Instead, they made my life worse.

— Lillian Oliva Bardales, Honduran immigrant

Last fall, she got a tourist visa to Spain, where she and her daughter awaited results of her appeal. In March, an appeals court ruled Bardales had not received effective legal counsel during her time in detention, and she and her son will be allowed to return to the U.S. soon and remain out of detention while their asylum case is pending.

“Justice is finally on the horizon for this young mother and her son after being severely abused and deprived of their rights for over a year by the Obama administration,” Johnson said.

Cintron and other immigrant advocates want Immigration and Customs Enforcement to provide detained families better access to counsel, advice about their rights and warnings about unscrupulous attorneys. They also want bar associations to have more oversight of private attorneys representing detainees.

“These women are desperate to save their lives. They will jump at the first opportunity to have an attorney,” she said. “I fear we have lost quite a few women because of this; I don’t know how many of these people fall through the cracks.”

molly.hennesy-fiske@latimes.com

Twitter: @mollyhf

To read the article in Spanish, click here.

ALSO

With echoes of Wounded Knee, tribes mount prairie occupation to block North Dakota pipeline

Capsule makes a splash in NASA test, and the scientists are pleased

Farmworker’s fatal shooting shows need for police training, Justice Department says

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.