Ben Valsler

You may have heard about sweet, fizzy drinks making people, children in particular, hyperactive. But there’s a compound in many fizzy drinks that can have quite the opposite effect, as Raychelle Burks explains…

Raychelle Burks

Coke, Pepsi, Dr. Pepper, Mt. Dew, Fanta… Some doctors and dentists say we’re drinking too much soda-pop, resulting in too many unwanted pounds and cavities. For one American man in the late 1990s, too much cola resulted in a visit to the emergency department of his local hospital. He complained of headache, fatigue, confusion, and an inability to control bodily movements (called ‘ataxia;). It wasn’t the sugar or caffeine that landed him in emergency care, it was the bromide.

Bromide can have a sedative effect. In the 1930s through the 1950s, inorganic bromide salts – like sodium bromide and potassium bromide – were nearly as popular as aspirin and just as readily available. Bromide’s sedative effect is due to its chemical family connection with chlorine. Both are halogens, displaying similar properties such as forming single, negatively charged ions: chloride (Cl-) and bromide (Br-).

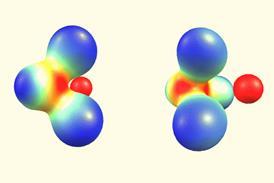

Communication between neurons depends on a carefully managed exchange of hydrated chloride. Bromide can stand-in for chloride, but [the hydrated bromide ion] is smaller, so slips into cells faster. A deluge of anions makes a neuron more negative than its resting state – this is called ‘hyperpolarization’. Hyperpolarized neurons are very difficult for other neurons to stimulate and this leads to the feeling of calmness or sedation.

A bit of calm doesn’t sound so bad, but the sedative dose of bromide is too near bromide’s toxicity level. Plus, bromide can accumulate in our bodies. Back in the 1930s-1950s, overuse of bromide products led to appropriately named medical conditions. Bromide-induced coma was dubbed ‘the bromide sleep’. General bromide toxicity was ‘bromism’. Outside medicine, if you were just a bit of a bore you were insultingly called a ‘bromide’.

Our soda-pop drinking man showed many of the symptoms of bromism – but how? Bromide salts and their products hadn’t been on the shelves for over 20 years by the time he landed in the hospital, and these salts were never a staple of soda-pop anyway.

Bromide salts weren’t in his drinks, but brominated vegetable oil was.

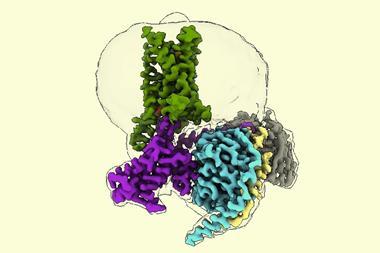

Brominated vegetable oil, called BVO for short, is made by adding bromine across the double bonds of certain fatty acids in vegetable oil, usually soybean oil. Like plain vegetable oil, BVO does a good job of dissolving water-insoluble food flavour, fragrance and colouring agents, serving as a carrier for these agents in soft drinks, which are mostly water. Neither plain vegetable oil or BVO is water soluble, but we can make oil/water emulsions, dispersing tiny droplets of flavour-carrying oil throughout a soda solution.

But why use BVO when plain ol’ vegetable oil could work? Density. Over time, gravity does its job and the emulsion breaks down, causing the oil and water to separate. If a plain vegetable oil is used, the oil fraction – which contains those all-important flavouring agents – would float to the top. Food scientists call this ‘creaming’.

One way to control creaming is to add some denser oil, adjusting the density until it matches the aqueous fraction. BVO is about 30% more dense than plain vegetable oil, so it’s a popular ‘weighing agent’. It also does a great job of keeping citrus oils, plus other fragrance or flavour oils, just where they should be in a beverage – suspended.

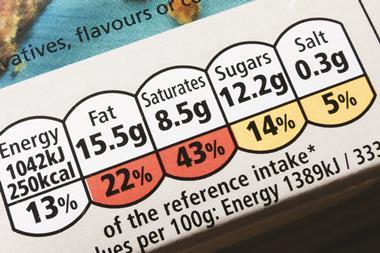

But is BVO safe as a food additive? The US Food & Drug Administration says BVO ‘may be safely used …in an amount not to exceed 15 parts per million in the finished beverage’. On average, soft drinks manufacturers use about 8 parts per million – not quite enough to totally prevent creaming, though it slows it way down. This concentration isn’t enough to cause bromism – normally. Our brominated man was no normal soda-pop drinker.

Research shows that Americans drink about 217 litres of soft drinks per year per capita. That’s about 600 millilitres per day, some of which might contain BVO. Our brominated man said he drank 2 to 4 litres of BVO-containing soda every single day for 6 months leading up to his hospital stay. That’s up to seven times the daily intake of his fellow Americans. That much soda, in that amount of time, brought him a case of bromism.

Typically, bromism is an easy condition to fix. While bromide’s ability to stand-in for chloride can cause problems, it also offers the solution to bromism. A patient is loaded with saline, a sodium chloride solution, and significant improvement is seen. But our brominated man required more than saline. He had to undergo hemodialysis to clear out all that bromide and help restore his ion balance. He ‘dramatically improved’ and, hopefully, drastically cut his fizzy drink intake.

Ben Valsler

Raychelle Burks on the counterintuitive sedation effect of brominated vegetable oil in otherwise sugary, caffeinated drinks. Next week, another compound you may find in the cupboards at home…

Brian Clegg

This simple inorganic compound is just NaClO – the only distinction from that common salt is that instead of a chloride ion it has hypochlorite with an added oxygen atom, but the transformation in the substance is striking.

Ben Valsler

Find out more with Brian Clegg in next week’s Chemistry in its Element podcast. Is there a compound you would like us to explore? Drop us a line on twitter to @ChemistryWorld, an we’ll see what we can do! Until next time, I’m Ben Valsler, thanks for joining me.

No comments yet