What We Need to Do the Job

We say it is a poor craftsperson who blames their tools.

We may get upset with a stubborn nail or lug nut, or when a pen goes dry. I admit there have been times when I considered throwing my printer through a window. We get frustrated when things we rely on to do our work refuse to do what we expect them to do.

It can be a challenge for us to admit we need help from things and from other people. We depend on tools and coworkers to do what we do. How we treat them says a lot about how we feel about what we are doing, even if they are inanimate objects.

Benedict’s Rule

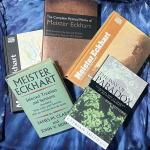

Benedictine monastic communities pledge to follow Benedict’s Rule. Written over 1,500 years ago, the rule gives guidance for many aspects of monastic life.

Benedict saw private ownership as an evil practice which was to be uprooted and removed from monasteries. Members of the community were to have free access to community property, but not own their own. The goods of the monastery, including tools, clothing, and anything else, were entrusted to the members. Members of the community were to keep its belongings clean and treat them carefully.

One member of the community was to be appointed to take care of the community’s things. This person was not to be annoying and to care for each of the other community members. This member was to regard the tools and goods of the monastery “as sacred vessels of the altar.”

This is a significant phrase. The tools each community used for manual labor are to be treated like objects used for worship. We should show the shovels and hammers we use the same reverence as the vessels on the altar.

Why is that important?

Benedict’s guidance is a direct challenge to how we understand and experience work.

We believe work is one thing and spiritual life is something completely different. For us, our professional lives are separate from our spiritual lives. Different rules apply, different standards of behavior, different expectations. We assume work is about making a living and getting ahead while spiritual life is more philosophical.

Many of us see work as dividing us into haves and have nots. We are told it is a dog-eat-dog world and our choice is to eat or be eaten.

We perceive spiritual life as a nicer, more polite world. Spiritual life is more about trust than about competition.

Benedict calls all our assumptions about work and spiritual life into question.

The tools we use for work are like the sacred vessels of the altar.

Sacred Vessels of the Altar

In the church where I am a member, our sacred vessels are made of silver. They are the chalices and small plates which hold the wine and bread for communion. Our central, common meal reflects what holds our community together.

We treat these vessels with a great deal of respect, bordering on reverence. We cleanse the vessels after each time they are used and polish them regularly. It is important we treat them well to keep us healthy and maintain their usefulness.

The sacred vessels of the altar are practical, even utilitarian. It is essential they do their jobs well. They are less sacred in themselves than in the way they support our common life.

While we may appreciate their beauty and brilliance, it is secondary to their service.

The tools we use to do our work serve the same purposes as the sacred vessels of the altar.

Tools and Utensils for Everyday Work

The tools we use for work each day are not sacred in themselves. We learn to use them well, find ways to discover their potential.

Like the vessels of the altar, our tools are powerful in their support for our common life. As much as I might love my phone, it is only as significant as what it allows me to do.

We want to improve how we work and it is easy to assume we are just one new tool away from greatness. When we get that one new book, that one new device, our problems will be solved. Our challenges are not really our fault, but those of our utensils.

It almost sounds as if we were blaming our tools.

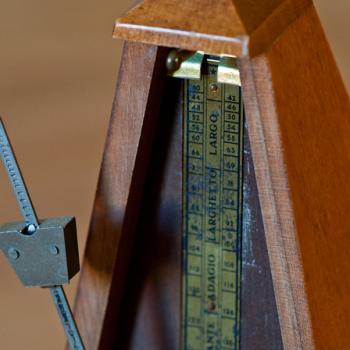

I love new tools as much as anyone else. There is sacredness, though, in holding tools which have been passed down through generations. We sense the presence of everyone else who has used those tools or worn those clothes.

Objects which have been put to good use are imbued with depth. I still have a sacred connection to tools which have taught me important lessons.

We live in a culture which teaches us things are disposable. It is easy to discard or recycle tools when they get old. We store things when we forget how they have helped us and deprive others of their use.

Our best tools live on in our memories of what they have taught us.

The Sacredness of Everyday Work

I inherited an assumption that becoming more effective was a product of gaining more power. It was a hammer and several nails which first taught me that might not be accurate. Over time, I began to question the idea that throwing ourselves again and again at a problem was helpful.

It began to dawn on me there might be a better, and even easier, way.

We learn by doing, by trial and error. Most of us need the experience of trying something to learn how it feels. It is the sense of the tool in our hands which teaches us what we need to do the job.

As much as we may value analysis or emotion, intuition or belief, it is practice which guides us.

How do you treat your most sacred tools?

What tool has taught you the most sacred lessons?

[Image by Lachlan]

Greg Richardson is a spiritual life mentor and leadership coach in Southern California. He is a recovering attorney and university professor, and a lay Oblate with New Camaldoli Hermitage near Big Sur, California. Greg’s website is StrategicMonk.com, and his email address is StrategicMonk@gmail.com.