Martin Luther King Jr.’s Assassination Sparked Uprisings in Cities Across America

Known as the Holy Week Uprisings, the collective protests resulted in 43 deaths, thousands of arrests, and millions of dollars of property damage

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b6/08/b608c067-f448-4aa6-b163-f0702c72c97f/lede-photo-1968-unrest-wr.jpg)

In April 1968, civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. made his way to Memphis, Tennessee, where sanitation workers were striking for a pay raise with the support of local ministers. On April 3, King delivered his “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech and made plans for a march to be held on April 5. But the evening of April 4, while at his lodgings at the Lorraine Motel, King was shot through the jaw. An hour later, he was pronounced dead at age 39.

Long before the public had any answers as to the identity of the assassin (a man named James Earl Ray, who pled guilty to the murder in March 1969 and was sentenced to life in prison, despite questions about the involvement of groups like the FBI or the Mafia), the nation was swept up in a frenzy of grief and anger. When King’s funeral was held the following Tuesday in Atlanta, tens of thousands of people gathered to watch the procession.

Despite King’s father expressing the family’s preference for nonviolence, in the 10 days following King’s death, nearly 200 cities experienced looting, arson or sniper fire, and 54 of those cities saw more than $100,000 in property damage. As Peter Levy writes in The Great Uprising: Race Riots in Urban America During the 1960s, “During Holy Week 1968, the United States experienced its greatest wave of social unrest since the Civil War.” Around 3,500 people were injured, 43 were killed and 27,000 arrested. Local and state governments, and President Lyndon Johnson, would deploy a collective total of 58,000 National Guardsmen and Army troops to assist law enforcement officers in quelling the violence.

King’s death wasn’t the only factor at play in the massive protests. Just weeks earlier, an 11-member commission established by President Lyndon B. Johnson had released its investigation of the 1967 race riots in a document called the Kerner Report, which provided broad explanations for the deadly upheavals. “Segregation and poverty have created in the racial ghetto a destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans,” the report stated. “What white Americans have never fully understood—but what the Negro can never forget—is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.”

While the conditions the Kerner Report described—poverty, lack of access to housing, lack of economic opportunities and discrimination in the job market—may have come as a surprise to white Americans, the report was nothing new to the African-American community. And at the time of King’s death, all those problems remained, including the need for access to housing.

President Johnson openly acknowledged how painful King’s murder would be to African-American communities, in the context of all that they’d already suffered. In a meeting with civil rights leaders following news of King’s death, Johnson said, “If I were a kid in Harlem, I know what I’d be thinking right now. I’d be thinking that the whites have declared open season on my people, and they’re going to pick us off one by one unless I get a gun and pick them off first.” Although Johnson successfully pushed Congress to pass the Fair Housing Act of 1968 (which prohibited discrimination in the sale, rental and financing of housing) four days after the assassination, the legislative victory was a meager palliative in the face of the loss of Reverend King.

To better understand the days following King’s death, explore the responses of five cities across the country. While all were united in mourning the loss of a civil rights champion, the conditions in each city led to varying levels of upheaval.

Washington, D.C.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/84/81/84818406-4531-421f-af86-d604b66f884a/dc-riot-wr.jpg)

Of the dozens of cities involved in uprisings and demonstrations after King’s death, the nation’s capital experienced the most damage. By the end of 12 days of unrest, the city had experienced more than 1,200 fires and $24 million in insured property damage ($174 million in today’s currency). Economic historians would later describe the Washington, D.C. riot as on par with the Watts Riot of 1965 in Los Angeles and the Detroit and Newark riots of 1967 in terms of its destructiveness.

Economic conditions largely fueled the upheaval; African-Americans made up 55 percent of the city’s population by 1961, but were crammed into only 44 percent of the housing, and paid more for less space and fewer amenities, writes historian Dana Schaffer.

Although activist Stokely Carmichael, a leader of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee, encouraged businesses only to remain closed until King’s funeral, he couldn’t stop the crowds from turning to looting and arson. One young man who witnessed the rioting told Schaffer, “You could see smoke and flames on Georgia Avenue. And I just remember thinking, ‘Boy it’s not just like Watts. It’s here. It is happening here.’”

It wasn’t until President Johnson called in the National Guard that the rioting was finally quelled. By that time, 13 people had died, most of them in burning buildings. Around 7,600 people were arrested for looting and arson, many of them first-time offenders. The fires that ranged across multiple neighborhoods left 2,000 people homeless and nearly 5,000 jobless. It would take decades for the neighborhoods to fully recover, and when they did, it was mostly gentrifying white professionals reaping the benefit.

Chicago

African-American communities in the Second City had a special relationship with King, who in 1966 lived in the poverty-stricken West Side while campaigning for open housing in the city. Almost immediately after news of King’s death arrived, looting and rioting began. One local of the West Side told the Chicago Defender on April 6, “I feel this is the opening of the door through which will come violence. Because of the way Dr. King died, I can guarantee it’s gonna be rough here.”

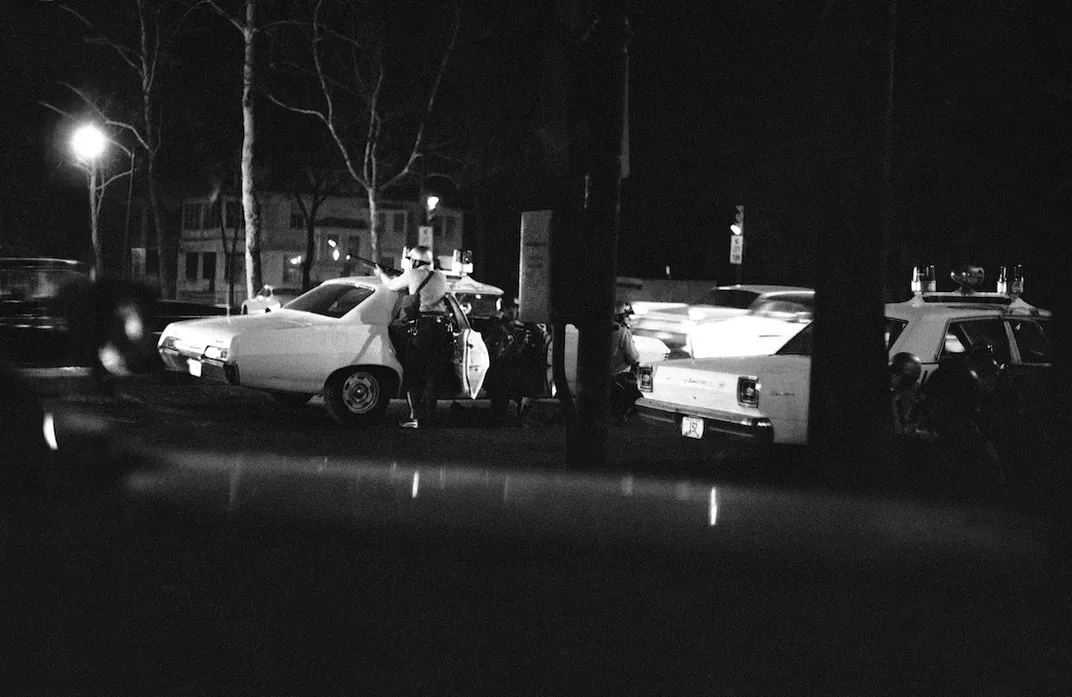

By Friday evening, the day after King’s assassination, the first of 3,000 Illinois National Guard troops began arriving in the city and were met by sniper fire in West Side neighborhoods. Mayor Richard Daley ordered police to “shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail” and to “shoot to maim or cripple anyone looting any stores in our city.” By the time the protests came to an end, 11 people had died, of which seven deaths were by gunfire, reported the Chicago Defender. Nearly 3,000 more people were arrested for looting and arson.

As in Washington, protestors saw their actions in the broader context of segregation and inequality. “Violence is not synonymous with black,” wrote a columnist in the Chicago Defender on April 20. “Who shot President Kennedy? Who shot King? The black revolt is a social protest against intolerable conditions that have been allowed to linger far too long.”

Baltimore

Of all the cities that saw unrest in the wake of King’s assassination, Baltimore came second only to Washington in terms of damage. Although the crowds that gathered in East Baltimore on Saturday. April 6. began peacefully, holding a memorial service, several small incidents that evening quickly led to a curfew being set and the arrival of 6,000 National Guard troops. The protests that erupted thereafter led to nearly 1,000 businesses being set afire or ransacked; 6 people died and another 700 were injured, and property damage was estimated at $13.5 million (around $90 million in today’s currency), according to the Baltimore City Police Department.

It was a tumultuous, terrifying week for those living in the neighborhoods under siege from protestors and law enforcement. “The Holy Week Uprising engendered a great deal of fear. Fear of getting shot, of being bayonetted by the Guard, of losing one’s home, of not being able to find food or prescription medicine,” writes historian Peter Levy. Making matters worse was Maryland governor Spiro Agnew, who blamed African-American community leaders for not doing more to prevent the violence, describing them as “circuit riding, Hanoi visiting, caterwauling, riot inciting, burn America down type of leaders.” Agnew’s response to the riots, and to crime more generally, drew the attention of Richard Nixon, and led him to recruit Agnew as his vice presidential running mate later that year.

The upheaval continued until April 14, and only came to an end after more nearly 11,000 federal troops had been deployed in the city.

Kansas City

In a city stretched across two states, on the Kansas-Missouri border, Kansas City was a telling example of what could happen when a community’s desire for peaceful demonstrations were stymied. After King’s death, the Kansas City, Kansas School District canceled classes on Tuesday, April 9, so that students could stay home and watch the funeral. In Kansas City, Missouri, however, schools remained open.

“When school authorities rejected their request, the young people [of Kansas City, Missouri] began to demand that they be permitted to march to City Hall to protest,” recalled Revered David Fly, who participated in the marches that week. Initially, it seemed as if the students might achieve their desire to demonstrate; Mayor Ilus Davis ordered police to remove barricades they had installed in front of schools. He also attempted to march with the students to show his support. But for reasons that remain unclear—perhaps because a student threw an empty bottle at the police line—law enforcement unleashed canisters of gas into the crowd.

“Students began running as the police in riot helmets and plastic masks charged into the crowd with tear gas, mace, dogs and clubs,” Fly said. Over the next four days, vandalism and fires plagued the east side of the city in Missouri (Kansas City, Kansas was largely unaffected thanks to the proactive efforts of city officials to memorialize King). More than 1,700 National Guard troops joined police officers to disrupt the rioting and arrest nearly 300 people. By the end of the protests, 6 people had been killed and city damages totaled around $4 million.

New York City

Despite President Johnson’s empathy toward the “little boy in Harlem” responding to King’s assassination, New York City proved to be one of the exceptions to the broader unrest. Although Harlem and some neighborhoods in Brooklyn experienced fires and looting, the damage was relatively minimal. This was, in part, due to the efforts of Mayor John Lindsay.

As deputy chair of the commission that wrote the Kerner Report, Lindsay was well aware of structural inequality and the problems that plagued African-American communities. He pushed the Kerner Commission to demand federal spending efforts to undo decades of segregation and racism. When Lindsay learned of King’s assassination, he ignored the advice of aides and immediately headed to Harlem, writes historian Clay Risen, author of A Nation on Fire: America in the Wake of the King Assassination. At 8th Avenue and 125th Street, Lindsay asked police to take their barricades down and addressed the growing crowd, emphasizing his regret that the death happened. Lindsay also met with students marching from City University of New York and civil rights leaders.

Although 5,000 police officers and firemen were deployed around the area, and some arrests were made, the city emerged from the weekend relatively unscathed. “Everyone agreed that Lindsay had made a huge difference by showing up at a time when many mayors across the country were hiding out in bunker-like emergency operations centers,” Risen writes.

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/accounts/headshot/lorraine.png)