Mourad Boutros interviews Peter Rosenfeld, whose 35 years’ work in type influences how we read the same way in different scripts

Peter Rosenfeld has crafted a career in designing fonts. After finishing his business studies (marketing & sales) in 1980, Rosenfeld started work as a junior sales manager for fonts at Dr. Hell in Kiel, Germany. During his two-year stay, he was trained in typography as well as in digital font production. In 1982, he left Dr. Hell to start a new position at URW Software & Type, a young software-development company focusing on digital font design and production in Hamburg, Germany. Within a few years, Rosenfeld had become the manager for the URW font department, responsible for both the font production and font marketing and sales for OEM clients as well as users of a URW proprietary sign-making system (SIGNUS). During this period and under his guidance, URW developed well over 1,000 digital fonts for the URW library and hundreds of fonts for IKARUS customers such as Letraset, Monotype, ITC, Scangraphic, and many more. In 1995, Rosenfeld and his partner Dr. Jürgen Willrodt founded URW++ after having acquired URW’s IKARUS software system for font design and production as well as the legendary URW font library of about 2,500 ultra-high quality outline fonts, which both of them had helped to build. Ever since, Rosenfeld, Jürgen, and the entire URW++ team of type experts have expanded the font library, especially relating to non-Latin fonts.

Language Magazine: What are global fonts? Are they a family of fonts that would enable a global brand to present a consistent typographical image across all countries, languages, and writing systems, or are they merely a series of font bundles comprising a broad range of writing systems that can be used on a global basis?

Peter Rosenfeld: The development and expansion of global markets and new technologies have brought new challenges and demands for font manufacturers. New products keep pushing into the Near East and Asian markets. In order to be successful, such products must be equipped with Asian writing-systems fonts, such as Arabic, Hebrew, Cyrillic, Devanagari, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and many more. The world has become a global village during the last two decades. The internet has locally connected completely separated regions and information is traveling in seconds around the world. English has been the lingua franca of the internet in its early days, but now communication is happening in all languages. Look at Wikipedia, available in more than 100 languages and viewable in their native scripts. Multilingual fonts are an important building block of the architecture of the World Wide Web.

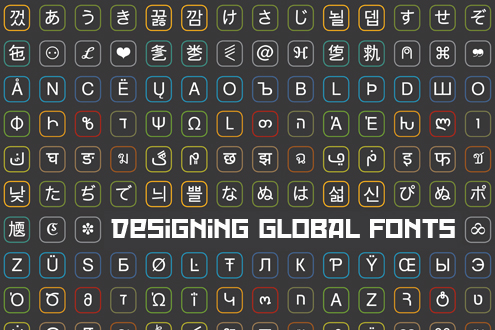

Global fonts in general cover all languages and writing systems commercially relevant and demanded. URW global fonts contain up to 65,000 characters per style, the physical boundary of TrueType. All scripts within a global font should be harmonized in weight, style, and flavor. Last but not least, a true global font must contain OpenType language features for complex scripts, such as Arabic and Indic scripts. URW’s global fonts are indeed designed to enable a global brand to present a consistent typographical image across all countries, languages, and writing systems. Nimbus Sans Global [pictured left] and Nimbus Roman Global, URW’s two global font families, are available off the shelf representing a standard grotesque (sans serif) and roman (serif). However, it is even possible to design and produce an exclusive, customized global corporate font family with all 65,000 glyphs per style exclusively designed as a corporate typeface (Siemens, Daimler, Nokia).

LM: Is the former actually possible and, if so, what possible advantages could there be? For instance, why would a global brand manager want to do this at the level of the written word rather than simply the brand logotype itself? Is it not sufficient for the logotype on a print advertisement to be converted into another language following the same colors, style, and layout of the original? What advantage could there be for the text to be consistent and would anyone other than a typographer notice?

PR: Type is a relevant part of corporate design, next to the logo and color. The internal communication as well as the company image is determined by it. Type can generate a high level of brand recognition and thus provides identification with the company, both internally and externally. The fact that it is not consciously perceived as often as the company name and the company logo does not diminish its significance. It is a proven fact that it greatly influences the unconscious perception of a company.

LM: Could you tell us something about the technology involved in creating a global font? What are the obstacles to overcome?

PR: Not only is the design of foreign language scripts a challenge, but the production of these large and complex fonts is a huge task which requires a lot of know-how. One has to understand the required technology and also to understand the syntax of the language. Ideographic language systems like Chinese contain an incredible number of glyphs; alphasyllabary scripts like the Indian scripts or the Southeast Asian scripts are following really complex rules. The OpenType technology to represent and process these complexities on a computer is about 15 years old and creates for the first time the opportunity to communicate world wide.

LM: Are there any languages that have to be excluded from the concept of a global font?

PR: No, the only boundary is the technical two-byte restriction of TrueType with a maximum of 65,536 glyphs in a font.

LM: Obviously, some languages will be creatively and technologically less demanding than others. Could you give us some idea of the hierarchy of these languages, i.e., which are the easiest and which are the most difficult?

PR: URW++ has designed and produced thousands of Latin typefaces and hundreds of Greek and Cyrillic alphabets. Obviously, these closely related scripts are creatively and technologically less demanding than other more ‘exotic’ scripts like Arabic, Indic, or Chinese for us. In order to be able to develop global fonts, you cannot but get really into it. Of course, we understand and appreciate that non-Latin scripts need to be designed by or at least under the control of native type designers from the respective countries or areas of the world. We started to build a global network of type designers, partners, and joint ventures in the early 1980s in order to learn about the design and production of all the non-Latin scripts. Chinese is very complex in terms of numbers of ideograms. A complete GB 18030 Chinese font contains about 30,000 glyphs plus another 8,000 design variants for Taiwan and about 3,500 for Hong Kong. This is an incredible amount of design and production work. It is easy to understand that Chinese fonts must be created by a team, rather than by one individual alone. Chinese is not related to Latin at all. The Chinese ideograms have developed completely independent from Latin. The same [degree of difficulty] is true for Japan, with a combination of kana (syllables) and about 8,500 kanji (Chinese ideograms adopted by Japan in medieval times and adjusted over time to better reflect the Japanese culture). Korean hangul, with over 11,000 syllables, is another design and production challenge. Although the basic design of the syllables is not as complex as in Chinese, the challenge lies in the combination of the syllabic blocks.

Like in Latin, white space is of major importance, and every single glyph needs design attention. Chinese and Japanese are written both horizontally and vertically, which requires specially designed characters, e.g., punctuation, for vertical setting and according language features. Even more complex, relating to language features, are scripts like Arabic. This beautifully flowing script requires every character to have variants for initial, medial, and final setting depending on its position in a word. Aside from designing all characters three or four times for individual position, the fonts must carry the corresponding language features for positioning (GPOS) and subsetting (GSUB). At this level, a fully equipped global font becomes more of a program, much more complex than single-byte fonts from the past. Finally, a global font needs to come with the major Indic scripts. Indic scripts are even more complex than Arabic, because not only are there different character shapes depending on position, but on top of that, characters can move vertically and horizontally besides changing form — incredibly complex. We have been working on a set of ten Indic scripts for the last three years, and we are not yet done.

LM: Do global fonts have anything to do with creativity and design? Are they not more geared toward technological information systems that can process data in different writing systems? In other words, are not global fonts designed for reading and processing orders, usage instructions, packaging, and other embedded devices rather than for designers and typographers?

PR: Yes, the initial demand was for a set of technically perfect fonts with all different writing systems including language features for embedded devices of all kinds, translation systems, user manuals, packaging, and so on. However, pretty soon, clients like Daimler, BMW, and Siemens, who are selling their products around the world, started to ask for real global fonts individually designed to fit their existing sets of corporate fonts. Ever since, we have designed a number of additional, partly exclusively designed sets of global fonts. Look at the corresponding websites, advertisements, annual reports, etc. All designed and created by typographers and designers for such clients. The demand for individual, exclusive global fonts is growing, resulting from ever more companies selling products globally. Think of companies selling fashion, sports, luxury goods, you name it. Many of them will have a need for corporate global fonts completing the corporate design.

LM: Is there not a danger that the drive to achieve consistency on a global basis will undermine creativity and individuality on a local basis?

PR: No, not at all. Driven by the economic strength of the Asian countries, there is much more interest in type design and typography in these countries, and we are seeing a lot more new typefaces from local designers than before. Type conferences are held in India, China, and Japan, manifesting the growing interest in local font design and typography. Also, type designers from Asia see the potential of working for Western clients. We at URW are used to working with designs and experts from around the world. It is fascinating and educative at the same time. Today, global fonts are primarily used by global players. However, as stated before, the world has become a global village during the last two decades. Multilingual fonts are an important building block of the architecture of the web, and we can expect to see a lot more designers and typographers around the world using global fonts for web design and web typography.

Mourad Boutros, of Boutros Fonts, has been designing type since 1966, and is author of Talking about Arabic and Arabic for Designers. For more on Boutros’s work as a type designer and designing Arabic type, please see the August 2011 issue of Language Magazine.